Since 2008 Les Enfants Terribles have been wowing Edinburgh audiences with their combination of strong physical storytelling, vaudeville styling (episodic storytelling combining ‘turns’, puppetry, wild costumes and song) and new writing from one of the two directors Oliver Lansley, who also stars. The Trench comes to Brighton Fringe hot from a barnstorming Edinburgh run with a clutch of strong reviews, but its combination of repetitive couplets and oddly static sung interludes of repeated actions (rhythmic show shining – check!) really left me cold.

The show opens with a group of shadowy figures crouched on stage against the imposing flats of Sam Wyer’s trench design. The auditorium is filled with thick haze and an air of sombreness and leaves you in no doubt that this is a show that takes itself seriously. Its story – of a doomed miner entombed beneath his trench, which is only the beginning of a strangely fantastical adventure – unfolds in old fashioned rhyming couplets, a form the company have developed through previous shows such as The Terrible Infants (a variation on the cautionary tales genre similarly explored by Improbable Theatre). In that context the rhyming makes sense – a witty variation on Hoffman’s style – but here it rings oddly: with no obvious connection to the story’s material, the pentameter feels inflated and the writing is simply not good enough, with pronunciation and emphasis often mangled to hit the iambic pentameter and justify its use.

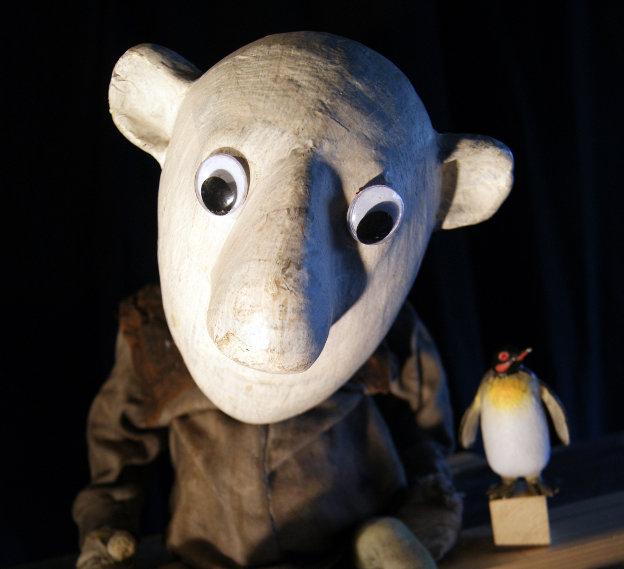

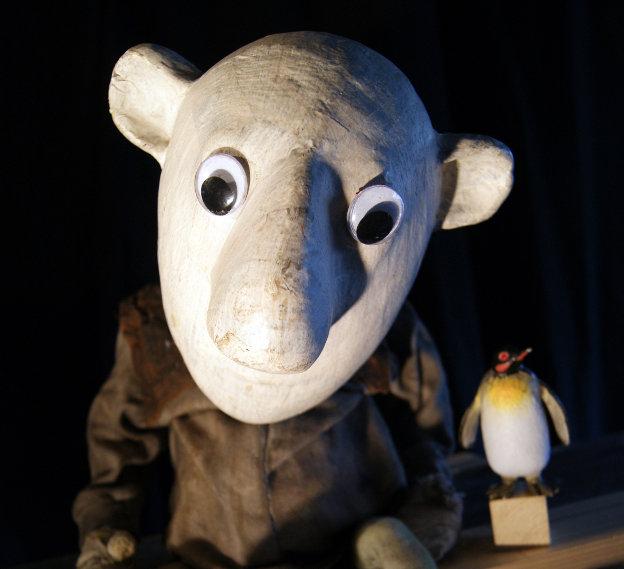

The show is at its best when demonstrating a deft eye for poor theatre transformations (planks become a mine shaft, with dropping coins as earth falls ominously overhead), and the excitingly designed discoveries of the large-scale puppets are realised with boldness and aplomb. But it’s at its worst when it gives in to its own sense of grandeur as it hammers through plodding pentameter or in the over-extended sub-Radiohead styled songs during which the action stops completely.

I also have some political objections to the story: devising a tragic beginning for your protagonist’s narrative (who suffers a devastating blow just before his tunnel caves) smacks of making it ‘okay’ for them to march off into the light at the end. How much more brave and profound it could have been to show the soldier making a real sacrifice for his friend by saving him when he himself still had it all to live for, or to show both dying as a result of the mindless conflict they were caught up in. It seems to me naïve to make a piece of work on this subject without thinking through the political ramifications of your creative choices. And I couldn’t shake the feeling that there’s something rather lacking in taste or sensitivity to take such a historical moment, already saturated in drama and action, and instead feel the need to overlay your own quasi-mystical quest story over the top to develop your subject.