Michael Begg surrounds himself with sound at Sonica in Glasgow

They are a form of theatre. They are compositions in space that effectively pull one into a sense of something other, another time, place, dimension. There is often a narrative waiting to be interpreted. Often, too, there is scenery and sound, and some form of dialogue. When successful, they form eruptions opening into parallel possible worlds, inviting us to consider the familiar in new light, or the unfamiliar in first light.

The installation is more seductive, less confrontational than its sibling the performance art action. There is seldom any performer commanding your attention, let alone your reaction. There is only the work statement, the evidence of a proposition made manifest in place and time left to do its thing, left for you to do your thing to it, left for you to make what you will, take what you will.

They are a form of theatre, but the fourth wall is more likely to arise between yourself and your neighbour than the pair of you together against the work. It is a very intimate form of theatre, because you are, when engaged fully, a practitioner.

For 21 years, Cryptic, in the tenacious hands of artistic director Cathie Boyd, has pursued a singular vision of the Art House, producing, commissioning, nurturing and touring works that resolutely fail to sit within recognised borders; performance and spectacle; sound, music and light; technology and craft. Sound – experimental, electronic music, in particular – becomes more of a specific focus of this border breaking activity within Cryptic’s Sonica strand.

The biennial festival, this year in its third iteration, manifests over 11 days as a city-wide combination of performances and installations. The installations arise from commissions, residencies and through the Cryptic Associates programme for emerging artists and are, on occasion with inspired verve, sited in a range of venues including the Centre for Contemporary Art, the Glasgow Science Centre, The Glue Factory (which is what it says on the tin though has now been re-imagined as a multiform creative space), and Govanhill Baths which similarly is re-awakened from its original Edwardian purpose to live again as a community focused cultural hub.

Robbie Thomson: The New Alps

Govanhill Baths, mostly emptied of water, though still featuring walls slightly verdant with damp and, on account of the roof needing some attention, subject to an occasional drip in inclement weather, plays host to two very different responses to human short sightedness, folly, and self-determined capacity for ruin. Robbie Thomson’s The New Alps speaks to our propensity for imposing monstrous interventions upon the planet, which are then abandoned to become man-made landscapes of wreckage and ruin that outlast our individual lives.

Stepping down into the partially drained pool, one walks among Thomson’s kinetic sculptures, comprising cables, wires, pistons, rusted sheet steel: the kind of detritus immune to decomposition to be found littering every landfill and urban vacant lot. Here, in Thomson’s obsessive machinations, we find sound making machines of this tangled wreckage, locked into their small repetitive movements and generating noises ‘emulating purpose in repetition’. Small spouts of water accompany rattling metal mechanisms, and cyclic piston rushes, and all the intricate devices seem somehow to be gathered around a stark, black monolithic representation of a power station; silent, sentinel.

Jompet Kuswidananto: Order and After

Next door, in Order And After, Indonesian visual artist and member of Teater Garasi, Jompet Kuswidananto, juxtaposes minimal symbolic objects to cast a deep shadow into telling moments of Indonesian history. A recorded singing voice projects fragmented melodic notes and texts including the testimony of a wrongfully imprisoned soldier and the presidential apology for military violence, as well as more recent intonations of the threats posed to religious freedom following the fall of the Suharto regime in the late 1980s. Three red rags lie inert, like pools of blood on the floor of the pool, half hidden in the brightly illuminated fog. Periodically, the flags arise, bright as new hope, and strong gusts arrive to blow the smoke away and allow the flags to dance in the air. But again and again, all too predictably, the currents of air die and the flags collapse once more.

MortonUnderwood: Contra

Further north, in the tank room of Glue Factory, a similarly cold and neglected space relocating its purpose through the efforts of committed communities of artists, one finds MortonUnderwood – the duo of instrument makers David Morton and Sam Underwood – with Contra, a site-responsive installation of their Giant Feedback Organ.

The organ utilises grain pipes, mics and active speaker cones to refine and tune low frequency feedback. Walking through the space, pulling on cords to activate individual tunings, one becomes quickly aware that sound, particularly at these sub bass levels has a certain viscosity. The sound does not uniformly fill the space. It alters in relation to where you stand, the shape of the overall space and how it meets soundwaves emitting from other sources. One can find oneself, therefore, met by solid walls of deep tone that resonate sensually within one’s chest cavity, then pass through standing waves of sound to be party to both simple and complex rhythms as soundwaves strike each other and fold in and around each other. Here, the visceral impact of sound as tangible, sensual substance finds its counterpoint in the stripped industrial space – all tiles, concrete, grime and smears, thick with the historic smell of boiled glue.

Kathy Hinde: Tipping Point

Elsewhere, in the more refined spaces found within the Centre for Contemporary Art, where Cryptic maintain their offices, one finds a cleaner, altogether more cerebral aesthetic. Kathy Hinde’s Tipping Point, on the other side of the door – yet a thousand miles away – from the CCA café bar, is a fragile beast. Part software innovation, part realisation of the potential of glass as a performance tool, Tipping Point offers a balanced ecology of cause, effect and consequence. Islands of light in a blacked-out space each contain a mechanical contrivance containing balances, counterweights, and glass tubes containing microphones into which controlled measures of water – controlled, that is, by each container’s temporal alignment to the same activity occurring in the other tubes – drip down, creating feedback. Find a seat in the dark and there is much to be gained from allowing your attention to slip away and be carried off into abstract reflections, held aloft by the delicate, measured interplay of glass, water and electronics.

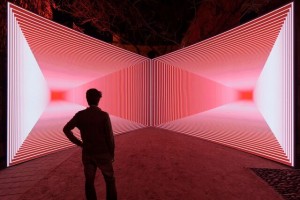

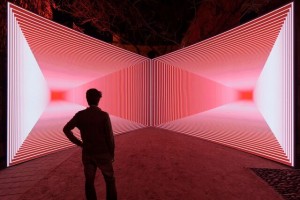

Olivier Ratsi: Onion Skin

Upstairs, Olivier Ratsi’s Onion Skin could not be more different to Hinde’s work. Propelled forward on a relentlessly motorik rhythm track, the gaze becomes transfixed on simple geometric planes of light tightly synched to the 5.1 surround-sound system which are projected onto two walls connected at right angles to each other. Over time, of course, the light and sound, excluding all extraneous connections, becomes hypnotic and what was plainly geometric shapes shrinking and growing on flat planes becomes persuasively suggestive of new spaces, twisting tunnels burrowing suggestively towards the promise of new dimensions.

I end my festival with a 45-minute walk in driving wind and slashing rain, through the architectural chaos sprawling along the south side of the Clyde. Retail malls and leisure park eateries cower meekly in the shadows of the motorway underpass, the derelict and crumbling warehouses, the cleared and forgotten fields of barren concrete, the brief architectural burps of new-build homes sharing busy street space with bars that you really don’t want to find yourself in and penny arcades. Then, into the twin blisters of modernist steel housing the Glasgow Science Centre. A thousand screaming Glaswegian children and their sleep deprived parents and guardians seeking refuge and stimulating distraction from the squalid day.

Wintour’s Leap: Helmholz

So, through all this noise and chaos, down into the basement one finds, tucked away in a corner between the main staircase and the toilets, a most singular island of peace and repose. Wintour’s Leap offer Helmholtz. In a curious echo to MortonUnderwood’s Contra, Helmholtz seeks to make sound visible, and in doing so, assist us in evolving an understanding of the differences in how various sounds navigate and claim space. A low hanging array of small lights, suspended at chest height from individual wires, occupies a space of around 50 square metres. The space remains in darkness until you speak, or cough, or clap, or sing – all of which you are encouraged to do. There is even a piano which has been left in the space for you to try. So, in playing small melodic lines in the dark, whispering into individual lights, or calling to a friend standing against a distant wall, the lights crackle into life as clouds, corridors, sheets, and fast moving waves. Like the best interactive, or reactive, applications, the success of the experience is completely dependant upon what – and how much – one personally puts into generating that experience.

Throughout the festival I became increasingly aware of the role played by the city itself. Sonica successfully occupied such a diverse range of spaces, and engaged so richly with the social and cultural fabric that a certain sense of optimism pervaded the activity. Similarly, the time and distance involved in negotiating the way from one event to the next invited a framework for reflection onto which the sights and sounds – very much the sounds – could not help but become entwined. That is the great achievement of Sonica, Cryptic and Boyd. The achievement reverberates through their 21 years of staging every possible size and shape and fashion of experience, and is most acutely tuned in Sonica. It is the living embodiment of what Alasdair Gray, in Lanark, proposes as the city becoming great through the capacity of its artists to imagine itself as great.

Featured image (top) is Wintour’s Leap: Helmholtz

Sonica Festival was presented by Cryptic in Glasgow, 29 Oct – 8 November 2015.

Sonica will stage a weekend programme at Kings Place London in February 2016, showcasing the work of Mark Lyken and North of X, as well as installations from Kathy Hinde, Sven Werner and Robbie Thomson.

A blacked out window of a shopfront in the trendy Echo Park area of Los Angeles stands in front of me. The words ‘RETURN TO FOREVER HOSUE’ have been pasted to the window. I wait outside, six others wander up, and we begin to tentatively talk to each other – How did you hear about the show? Have you ever done a locked room before? We’re going to have to work together…

A blacked out window of a shopfront in the trendy Echo Park area of Los Angeles stands in front of me. The words ‘RETURN TO FOREVER HOSUE’ have been pasted to the window. I wait outside, six others wander up, and we begin to tentatively talk to each other – How did you hear about the show? Have you ever done a locked room before? We’re going to have to work together…