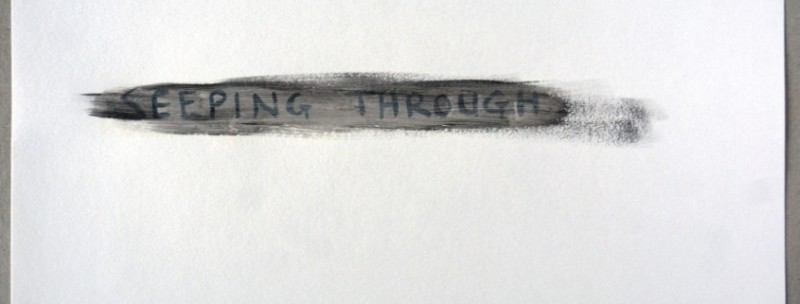

In this four-hour durational performance, Etchells and Orazbayeva perform simultaneously. Staged in a side room off the main space at the Drill Hall in a long thin space, Seeping Through placed the audience along one long side with the performers along the other long side. This made it difficult to enter or leave the space surreptitiously, and so the coming and going of audience members seemed to form part of the performance.

In this four-hour durational performance, Etchells and Orazbayeva perform simultaneously. Staged in a side room off the main space at the Drill Hall in a long thin space, Seeping Through placed the audience along one long side with the performers along the other long side. This made it difficult to enter or leave the space surreptitiously, and so the coming and going of audience members seemed to form part of the performance.

Tim reads aloud, repeating words and phrases from cue cards and the occasional A4 piece of paper while walking from side to side or sitting. Aisha uses her violin to create sounds, noises, and occasionally music. Tim Etchells chooses a phrase and then spends some minutes vocally exploring the variations of inflection, pace, intonation and meaning of the phrase. Sometimes he allows the phrase to evolve, changing the word ‘my’ into the word ‘your’ for example, and uses his right arm and hand to fling the words out, away, into the audience. Aisha explores the potential of her instrument, the violin and the bow, her fingers and loose horsehair to create a series of sounds. Sometimes as the volume rises or a rhythm emerges from her activities, Tim responds, but mostly they seem to be in their own worlds of performance.

Etchells never seemed to be all that comfortable with what he was doing, sometimes struggling to keep going. The final half hour saw Tim glancing more and more often at the clock, finishing with five minutes of the phrase ‘keep it simple’. Aisha seemed more relaxed about her activity in her standard musician’s blacks, though never acknowledging the audience and hardly looking up at Tim. She seemed completely unaware of Tim’s clock watching and played beyond the 9pm finish time, allowing the sound to find its own natural conclusion. This was intriguingly abstract play, with flashes where meaning and music seeped through.