Girls will be boys, and boys will be girls. It’s a mixed up, muddled up, shook up world. Yes indeedy. Once upon a time The Kink’s Lola was my signature tune when plying my trade as an ‘exotic dancer’. In those days (mid 1970s), I saw myself as a kind of drag artist – playing out feminine mores. After growing up wanting to be a boy, sporting trousers and a short haircut (rare for girls in the 1950s/60s) I’d discovered my femme self, and boy did I want to act it out. It’s a kind of normal thing nowadays, in the queer world anyway, this game-playing, this acting out of any aspect of the (gendered) self and switching of gender allegiances as and when you like, but then less so. Then, you were over here in this camp, or other there in that camp. Radical Lesbian feminists wore dungarees and banned people like me (people who wore dresses and make-up) from meetings. Make your mind up, girl – are you with us or against us? Bisexuality, and what we’d call ‘questioning’ nowadays, were the ultimate sins. Now, thankfully, we are in a time of greater gender fluidity. Enter stage left, ready to explore and celebrate this fluidity, Just Like a Woman – a weekend of performances, screenings, installations, and discussions, curated by the Live Art Development Agency for Sacred 2015 at Chelsea Theatre. We are here to experience women performing women, men performing women, and women performing men. And whatever else might occur.

I manage to see a fair amount of the Saturday programme. Arriving just before 7pm, I catch the tail end of Girls on Film, a screening of performance documentation and performance to-camera, featuring, amongst many others, Cassils (seen at SPILL 2015), CHRISTEENE (shortlisted for a Total Theatre Award a couple of years back), theatre and cabaret star Ursula Martinez, and perennial favourite at Sacred, David Hoyle – who this year is presenting The Pride of Ms David Hoyle (20 & 21 November 2015).

The Girls: Diamonds and Toads. Photo Anthony Hopwood

Before Narcissiter kicks off in the main theatre space, there’s time to take in The Girls: Diamonds and Toads in one of the smaller studios. This is a captivating installation piece – a tableau vivant referencing what the artists call ‘the ill-fated heroines of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen’, although personally I’d see more Perrault than Andersen in the luscious, Rococo imagery. Anyway, let’s not quibble about fairytale references – this is a wonderful piece of living sculpture: two ultra-feminine princesses bedecked in cream and pink taffeta silk dresses, adorned with roses and pearls, lying in state on a bed/table/altar; sleeping beauties frozen in suspended animation, although their eyes follow you around the room as you circle them – big wide eyes with eyelids groaning under the weight of enormous lashes, set in plasticised whiter-than-Snow-White faces, framed by shiny golden curls. One of the two captivates me completely – I can’t break the gaze, locked into relationship. I fight the urge to kiss her and break the spell. Maybe I should have. Instead, I gentle touch her stockinged foot.

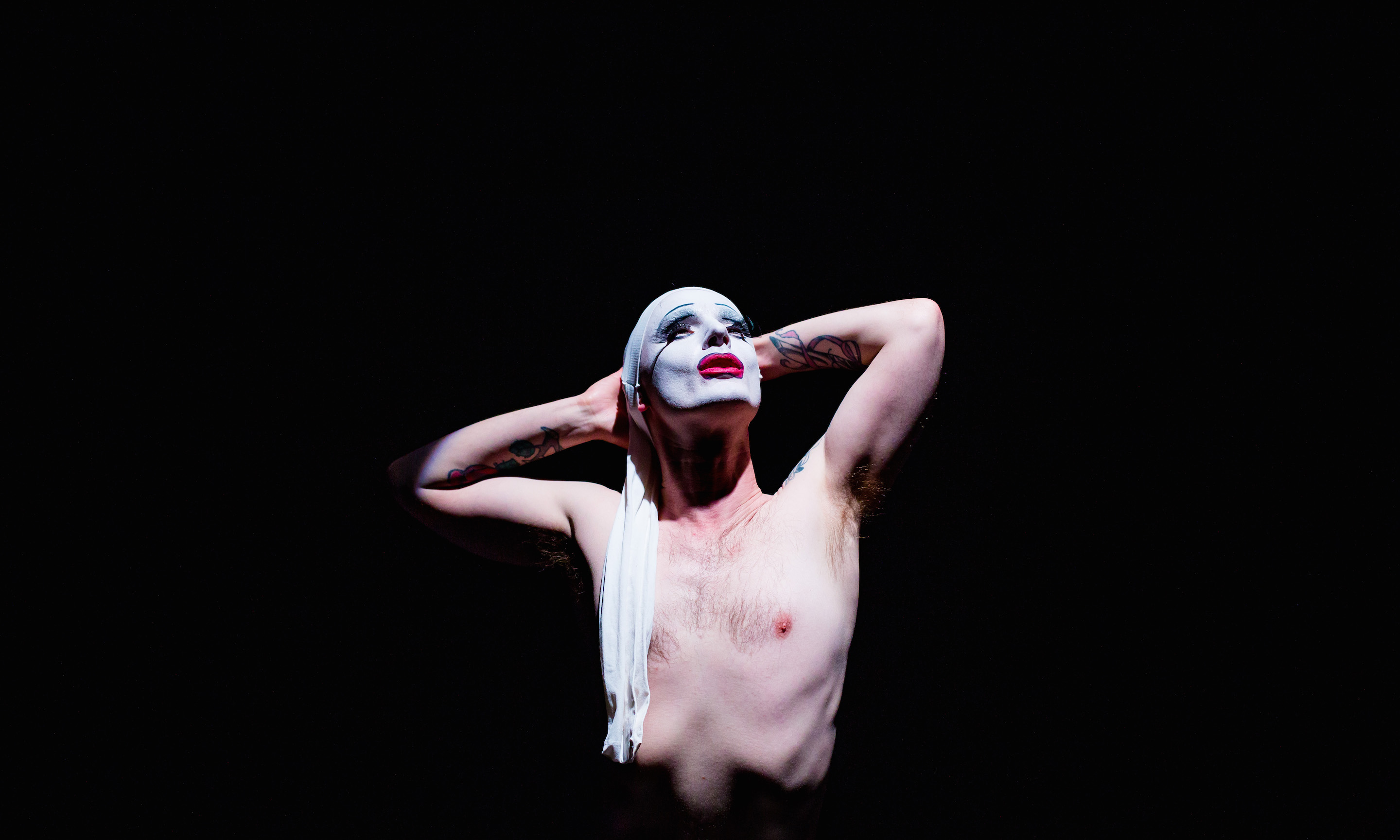

Narcissister

Upstairs we go for Narcissister: Conditions of the White Mask, my first experience of this New York legend, an artist of North African and other mixed heritage, whose name and face are kept hidden – Narcissister always performs wearing one (or often, many) of her trademark plastic masks. This turns out to be a wild and wonderful rollercoaster ride of live and filmed performance. Her doll-face masks, combined with her lithe, dance-trained body, give her the appearance of a Barbie doll come to life – an image played out most brilliantly in a performance video Burka Barbie in which the full-size Barbie Girl, in stripper heels and day-glo-pink backless dress, trolls through a trashy 99-cent store, working her way through the plastic-fantastic delights on offer, stopping to lovingly fondle the bubble-wrapped faces of the packaged dressing up dolls, becoming particularly fascinated with one with Arabic packaging. We are then thrown into the world of the dolls, as Burka Barbie comes to life and go-go dances wildly with her dolly mates to The Clash’s Rock the Casbah.

The live action is equally engaging. Narcissister’s entrance is as a kind of animated vanity-table cum dresser scuttling across the stage. The table turns out to be a baby’s basinet. The baby grows into a little girl with plaits, skipping merrily across the stage, then a young woman, a mother with a baby of her own, an older woman, a very old woman, and finally a corpse, back in the basinet-turned-coffin. This delightful, funny, and moving ‘seven ages of woman’ scenario is enacted with astonishing agility and precision, using face-masks, whole-body-mask, puppetesque false heads, and layers and layers of constantly morphing costumes. She twists and turns from one form to another: turning her back to us, she reveals a second mask on the back of her head; now, as she handstands, a further face appears; then, as she walks over from handstand to bridge, another face pops out from between her front-facing legs. It is a truly astonishing performance – rare to see someone with such physical dexterity on the performance art scene; a fabulous amalgam of physical performance and visual art/living sculpture that – although completely different, and very much its own thing – has echoes for me of the work of both La Ribot and Mossoux Bonte .

Harold Offeh. Photo OpenApertureUK

It’s all over far too quickly – but I’m afraid the same can’t be said for Harold Offeh’s Covers, seen next in the downstairs bar. In this piece, the artist restages, live, the images of black divas from the covers of a number of seminal albums from the 1970s and 80s. He stands there in a plain black leotard type garment, striking poses that echo the covers we see displayed on a monitor stage-left, as the music from each album plays. I can’t really work out what is being said here, about gender, about being Black, or about anything else. The divas are female, and this is a male body. And then what? The only one of the tableaux that interests me is his Grace Jones finale, and that because there is (at least) humour in his striptease, his liberal application of baby oil, and his struggling attempts to recreate Jones’s athletic pose on the Island Life cover. Maybe I’m reading this all wrong. Maybe it was all about the failure to live up to the divas, and I just don’t see the intention or intended humour in the other impersonations, I just see someone standing on a stage, vogueing and looking slightly awkward. Who knows? Sometimes you have to admit that you just don’t get something – and this is a case in hand.

LucillePower: The Butch Femme Touch Up Service. Photo Holly Revell

I go off to skulk around the bar, feeling a little tired and wondering whether to call it a night – but I’m then entrapped by three luscious ladies (of various sexes) dressed in vintage underwear (1950s stitched bras and big knickers) and wigs, who drag me over to a barber’s chair in the corner for Lucille Power’s The Butch / Femme Touch Up Service (a piece originally commissioned for Duckie Goes to Gateways, a celebration of the legendary Lesbian club). I’m given a make-up make-over – after some discussion, the beauty salon girls decide against a butch five o’clock shadow (my face must have given away how much I didn’t want this, although I would have quite fancied a moustache), and go instead for full-on femme. Neon orange eye-shadow, lurid peach blusher, and candy pink nail varnish slapped wildly on to nails (and onto a lot of my fingers, too). My black patent boots get a spit and polish, my crotch treated to a liberal dose of Femfresh (in case I should find myself in an intimate situation), and my barnet fluffed up and hair-sprayed. All the while, the girls gyrate and flirt and cosset and massage. Perfect! I did actually enjoy it a lot more than a recent experience of a ‘real’ pampering session in a hotel spa, which I found excruciating. But next time, a moustache perhaps?

Talking of moustaches, I regret missing The Drakes at JLAW on Friday evening, presenting The Butch Monologues, which explores the world of butches, masculine women and trans men. I am, though delighted to have caught at least some of the Gender Spectacle cabaret, which is MC’d by everyone’s favourite butch Peggy Shaw – alongside everyone’s favourite femme Lois Weaver. What a delight it is to see these two together on a stage again – and to know that Sacred is also including a Split Britches Retro(per)spective in its 2015 programme.

Eleanor Fogg’s johnsmith

I didn’t get to see much of the late-running cabaret, but I did at least catch johnsmith (the drag persona of Eleanor Fogg) with what it feels like for a girl, a lovely piece exploring transformation and duality, combining simple, exact, perfectly-controlled physical performance with a great soundtrack, to which s/he lip synchs. What we see is a business man in a suit, at first expressing the minor dissatisfactions and frustrations of the career man. This breaks down into a voice-distorted reflection on male hatred of all things feminine, a fear which disguises a desire to know, just for a minute, what it feels like for a girl. The tie is loosened, the shirt unbuttoned. Sexual politics that in some aspects suggest Jean Genet; sounds that in some ways echo the work of Laurie Anderson. Great stuff! I hope to see more of this artist in the future.

Talking of lip-synching, Dickie Beau’s Blackouts – Twilight of the Idols was shown in the Just Like a Woman weekender, seen by Total Theatre earlier in the Sacred season, and reviewed here. The Friday night also included performance by The Famous Lauren Barri Holstein, Live at World’s End, and the launch of the new book on Lois Weaver’s work, The Only Way Home is Through the Show, which is co-edited by Lois and Jen Harvie, and published by the Live Art Development Agency.

Dickie Beau: Blackouts

Featured image (top) is of Narcissister.

Just Like a Woman was previously presented at Abrons Arts Centre in New York, October 2015, and before that at City of Women festival in Slovenia in 2013.

Details of all works presented in Just Like a Woman, and the rest of the Sacred Season 2015 at Chelsea Theatre, can be found at www.chelseatheatre.org.uk

Just Like a Woman, 13 & 14 November 2015 and a companion weekender at Sacred, Old Dears, 27 & 28 November 2015, are the culminating events in the Live Art Development Agency’s Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three on Live Art and Feminism (2013–2015). See www.thisisliveart.co.uk