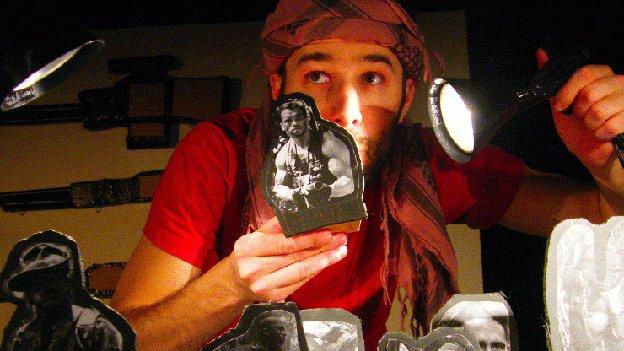

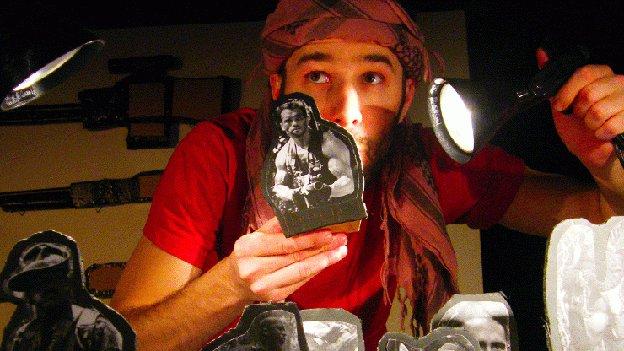

A game show that descends from a quest for the glittering prizes to an inhumane and degrading spectacle; some perverse partner dancing that ricochets from a twisted Tango to a slewed Swing; a surreal ballet with a mirror; a manic tug-of-war; a camp-fire tribal striptease; and a dreamy film landscape that suggests an Arcadia elsewhere…

Come on down, contestants, the price is right! Leave the material world behind and search for a universe in an atom; an eternity in the ticking of the Countdown clock…

Russian actor/dancer Tanya Khabarova (now resident in Italy), a founder member of the legendary Derevo, and long-term collaborator and former Derevo performer Yael Karavan (formerly of Israel, France, Italy, Russia, Brazil, Japan and now resident in the UK) have joined forces to create a new show together: ‘We feel the need to react to an unstable world and a life devoid of values where money and power have taken the place of conscience and sensitivity… a world in which the media and television have become our new gods.’

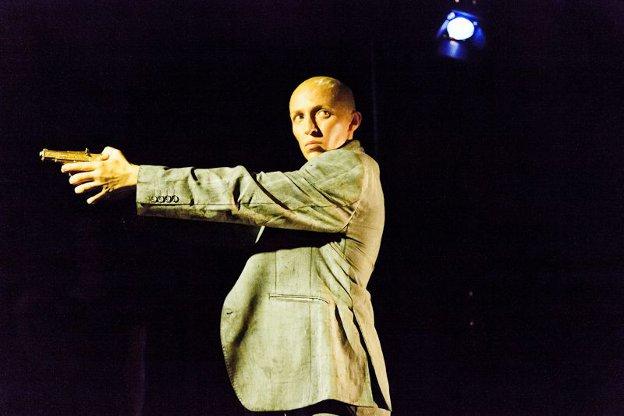

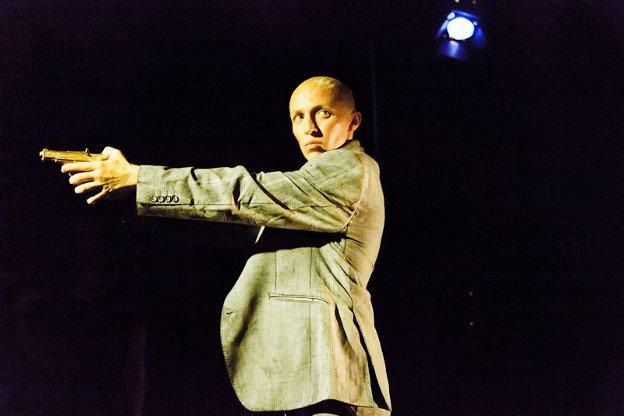

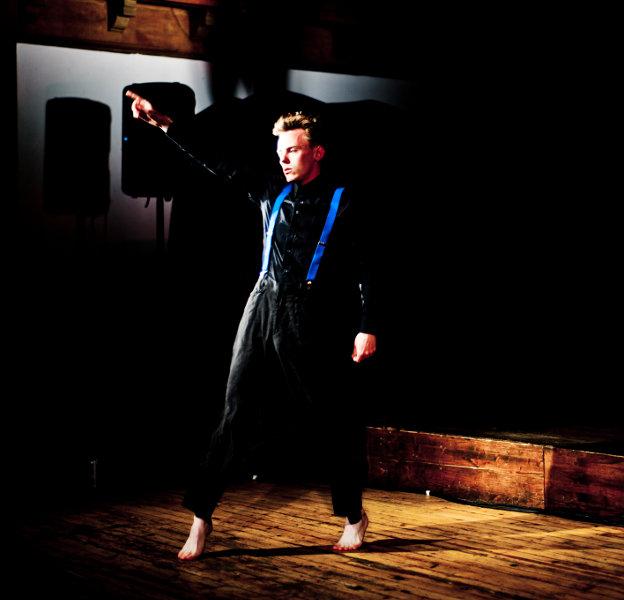

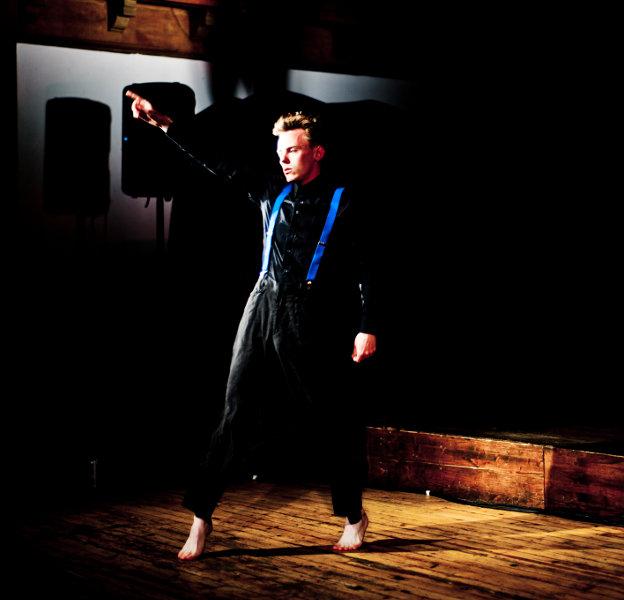

And so here it is. As we enter the performance space, we are sporting numbers stuck on our lapels. We sit to the sound of canned applause, and a game-show host’s cloying welcome booms over the PA. We wait to hear who will be chosen. I’m 723, and it’s not me. The lucky two are a young couple who take to the stage blinking uncomfortably into the spotlight. Of course, it is Tanya and Yael. Fix, fix! Yael plays a clownish version of a nervous young woman, the newly married girl-next-door. She fiddles with the lock of hair coming loose, and pulls her skirt down, showing her teeth in a trying-too-hard smile. The shaven-headed Tanya is completely believable as her ‘husband’, capturing the nervous machismo of the young male wanting to do his best. The slight twitch of the neck and shoulders, the brace of the legs, the glances at his woman, and the bravura face to the ‘camera’ – all note-perfect.

The game begins – a series of tasks and challenges released from a pile of numbered cardboard boxes; a kind of ‘seven deadly sins’ quest for further and deeper degradation that could also be seen as a descent through the circles of hell to the final abyss. ‘Lust’ brings a tortured tangle of limbs as bodies grapple to gain supremacy. ‘Greed’ sees a vaudevillian tussle over a wad of banknotes in a back pocket. ‘Vanity’ we presume is the aforementioned mirror-ballet, in which the ‘wife’s’ head becomes eerily replaced by the mirror held over it. There is an Adam-and-Eve reference in a gluttonous battle for an apple, and inevitably there is a gun. And, of course, once a gun enters a story…

The performance from both actors is beautiful, extraordinary – it’s a match made in heaven, and the unique physicality and ability of each, further enhanced by their shared history and jointly held ‘toolbox’ of physical theatre skills, makes for a mesmerising stage presence and onstage relationship. Each of the scenes, with its inherent tasks and battles, gives an opportunity for an intoxicating play between these two magnetic performers.

I’m a little less excited by the game-show frame for the piece. The game-show motif is a popular one right now: see, for example, the enormous success ofThe Hunger Games (a series of dystopian novels for teenagers, recently filmed); the Japanese story on a similar theme, Battle Royale; and Chuck Palahniuk’s new short story, Loser. Apart from the game-show-battle-to-the-death cultural phenomenon there is also, of course, a very obvious precedent for the daytime TV show send-up in Jerry Springer: The Opera. I cite these examples to say that although Somnambules is of course its own unique self, some careful thought could perhaps be given to how important the framing of the game-show is, and if it is considered key, then how this could be developed further in a new way. There is a danger in parodying cliché! In particular, a mock-interval ‘word from our advertisers’ feels a little tired, and the fact that although we get drawn into ever-more-surreal circles of imaginary worlds, I am slightly unsure if the game ever gets properly resolved. It is, no doubt, a deliberately ambivalent ending, but having been pulled into the action (albeit quite minimally) at the beginning, it seems odd to end without being pulled out again.

But it is early days yet for this show, as this was the premiere of the piece, and it will no doubt undergo many transformations over its next stage of development. The key thing though is the power of the performances, the strength of the onstage relationship, and the beauty of so many of the scenes – with work on the structure and framing, this’ll be a knock-out show. Game, set and match to play for!