We climb a forbidding flight of stone stairs and reach a high-ceilinged panelled room (this in the C Nova venue, the latest pop-up theatre space in the C Venues empire, housed in a government building). Almost the whole room is taken up by a large rusty-looking box, a kind of shipping container with peepholes. Peering in, we see what looks to be an austere prison cell – distressed white walls, a bare wooden table and chair, a sink with a dripping tap, and an unwelcoming metal bunk bed with no bedding.

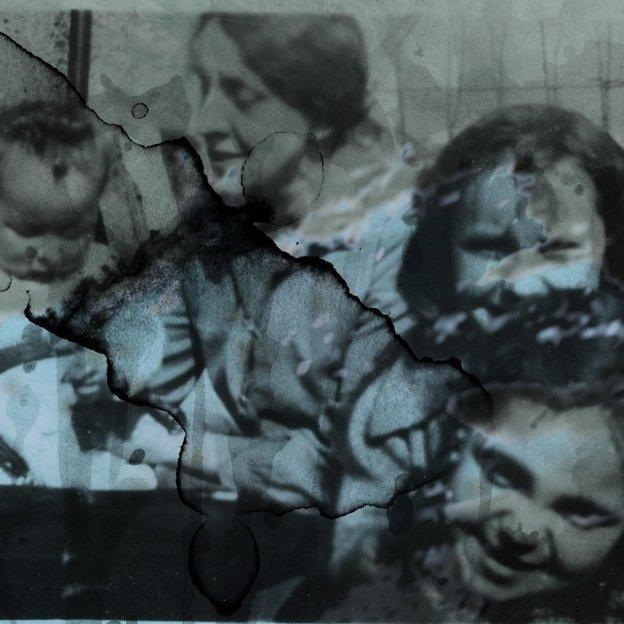

An usher opens a door in the container and invites us to enter, and we see two figures lying with their backs to us, bodies squashed against the wall – a woman on the top bunk and a man on the bottom. Over the next eleven minutes, a poignant choreography of angst, loneliness, frustration, and comfort-seeking is played out. An envelope on the table is opened slowly to reveal a letter and a grainy photograph, which is then stuck on the wall. A grille above the bunk bed becomes the scene of a dance of shadowy hands seeking escape. The bars of the metal bed are used to twist and weave through and over as our couple move with and against each other. Relationship to audience in the piece is interesting: the performers don’t acknowledge our presence, but we sit on stools holding torches that we may use in any way we wish – thus cast in the role of prison guards. Our torch beams create a dance of light and shadow around and upon the moving bodies.

There is no clear, determined narrative – instead, we construct narrative. In my head, the Hispanic appearance of the performers and the use of the black-and-white newspaper photographs conjures up memories of the terrible oppressions that took place in South America in the 1970s when so many people were captured and then ‘disappeared’. Other audience members will no doubt have their own thoughts and responses. There is also the possibility that this cell containing one man and one woman is a metaphor for the lifelong struggle of personal relationships.

This is not by any stretch of the imagination a circus show – but the circus skills of the two creator-performers (Marta Barceló and Joan Miquel Artigues) from this renowned Spanish company are evident, and the movement work is breathtakingly precise and gutsy. They are also masters of restrained physical acting – faces portray people who have trained themselves not to give themselves away to onlookers, with eyes that stare forward in blank pain, and small gestures of hopelessness are played with an admirable control and restraint.

Every element of the piece – design, lighting, sound, performance – is thought through carefully, each aspect contributing beautifully to the dramaturgy of the piece.

A visceral and thought-provoking physical theatre piece creating intense visual images that stay burnt in the mind long after we’ve left – some companies manage to say more in eleven minutes than others do in two hours!