‘You shouldn’t expect a story’ says someone at some point in Puppet. Book of Splendour. Well no, of course not. NeTTheatre’s latest work to make it to the Edinburgh Fringe is not afraid to tackle big subjects – the Kabbalistic tradition of Jewish mysticism, the struggle between existence and oblivion, the all-encompassing breadth of Judeo-Christian culture, history, philosophy and religion – presenting them with director Paweł Passini’s usual flair and daring. What we get instead of ‘a story’ is a multiplicity of stories, ideas and images about life and death, creation and dissipation, ein sof (no end) and the finite, weaving around and through each other and us in an exhausting but exhilarating hour-and-a-half of sensory onslaught.

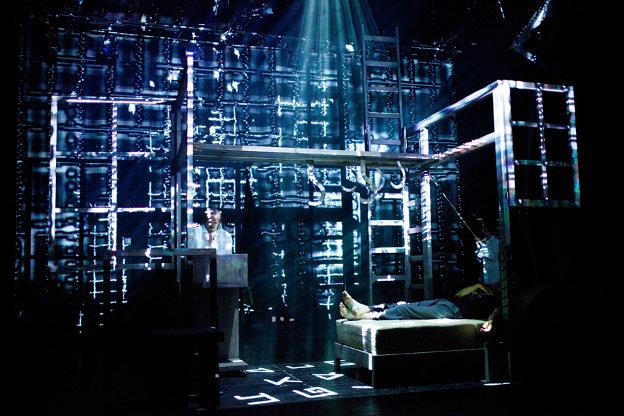

A Rabbi quotes from an ancient text in the Torah, an artist in a black beret (reminiscent of Tony Hancock in The Rebel, it must be said) waves his brush in the air in an anguished state, before collapsing exhausted on a bed. Is he God? Is he the architect of the world? A naked couple – Adam and Eve, we presume – struggle into a shared white shirt, keen to cover their shame. A strange black beast with a body of shiny leatherette prowls across the stage. From the mouth of babes: a child takes a book (probably a sacred book, perhaps the Torah) from a shelf, reads from it in a voice full of awe and wonder (‘he understands nothing, but he loves it’), then later gets on a tricycle to ride around the performance space in endless circles. The words Mercy and Justice and Kingdom and Paradise are broadcast from an upstage screen, and a host of white bubble-wigged angels pop out of a cabinet to serenade us. English, Russian, Polish – a babble of languages envelop us. Books and words, and words and books. And the Word was made Flesh…

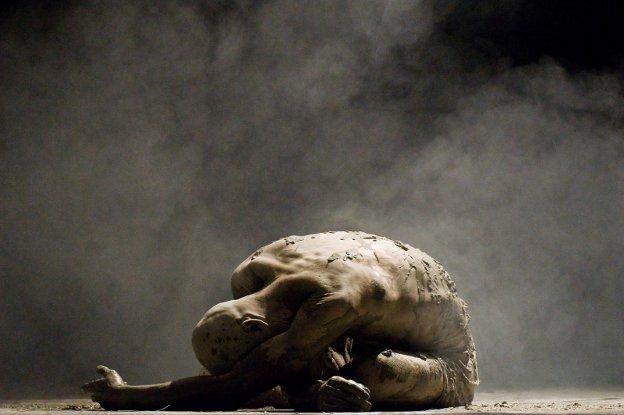

NeTTheatre’s Turandot won a Total Theatre Award in 2011, establishing the company on the Fringe as makers of complex and multi-layered visual, physical, visceral theatre in which music plays an important part. Puppet. A Book of Splendour similarly uses an extraordinary mix of live music and heightened visual imagery from high and low culture – and everything in-between – to create a glorious onstage stew of sounds and moving pictures. The Jewish myth of the Golem is a key theme in the show, and the notion of the ‘puppetesque’ is explored repeatedly throughout as dolls, mannequins, masks and animated clothing are used to create a series of effigies that appear and disappear (like the clay Golem of legend) – brought to life from inanimate matter by the human hand, a triumph of will and faith, only to then dissolve back into materiality.

Kantor – always acknowledged as an influence on the company’s work – is more directly referenced in this show, both in the stated desire to investigate and explore Kantor’s theory of a Theatre of Death (‘and its unexpected neighbour, childhood’) and in much of the physicality – there’s a nice overcoats-and-hats knees-as-feet shuffle dance at one point that is a homage to a scene in The Dead Class. The physical work – solo, duet, trio or ensemble – is of a very high standard throughout, and a word of praise here for the extraordinarily talented child-actor who held his own in this talented ensemble of eleven actors and singers.

The stage area is rather too small for this large ensemble, and is additionally crowded out with towers, screens, beds, cabinets, tricycles, chests, mannequins and whatever else. I am sure that it is all intended to be a glorious mess, but I would have thought a mess that needs some space to expand, rather than exploding out from the audience’s feet with nowhere to go. It is very difficult to read the surtitles from the front rows – and the words are obviously an important element in this production. It’s also extremely hot in the Summerhall main space, and the 90 minutes of the show drags a little. I am happy to concede that this is a ‘Fringe’ problem rather than something intrinsically wrong with the show – performing/watching a longer-than-average and complex show late-night in a crowded, unsuitable space is not ideal.

What the answer is for shows of this quality and complexity and how they can fit into the Fringe format is obviously a question for future Edinburgh presentations by neTTheatre and other enterprising and adventurous companies of this calibre. Regardless, this is a show that has stayed with me – one that I would dearly like to see again as I feel I have only scratched the surface of experience and understanding.