Girl, 18. She’s dressed in a loose pink jersey and skinny jeans, limp blonde hair falling over her face, no make-up. There’s an echo of the Corinne Day photos of the young Kate Moss in her cool and loose prettiness. She’s sitting on the floor next to a young man, and they’re talking in a relaxed way as the audience enters.

Girl, 18. She’s dressed in a loose pink jersey and skinny jeans, limp blonde hair falling over her face, no make-up. There’s an echo of the Corinne Day photos of the young Kate Moss in her cool and loose prettiness. She’s sitting on the floor next to a young man, and they’re talking in a relaxed way as the audience enters.

A slide projector is switched on: images clunk by, amused laughter from the audience as standard teen maxims and Facebook faves whirr by: ‘The Kids are NOT Alright’ and ‘Fuck the Pope – but use a condom’. Amongst them is one with rather more resonance: ‘Protect me from what I want.’

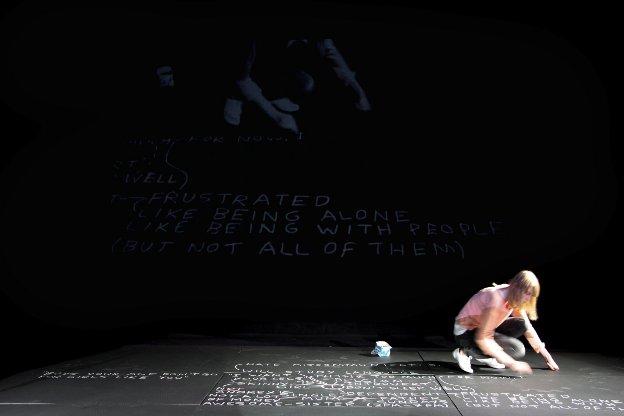

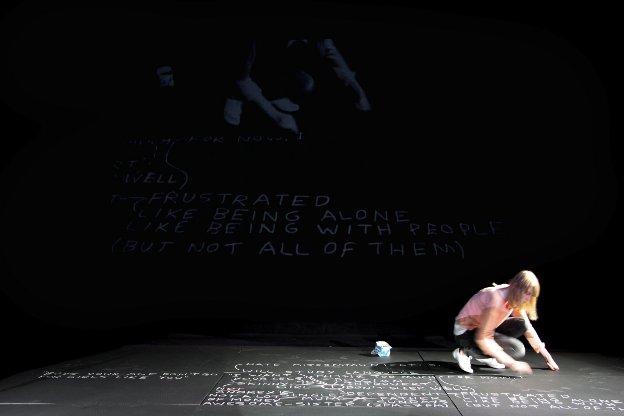

Next, a word chalked on the floor: ‘I’. From that one tree-trunk word grows branches and offshoots. First come the factual details (girl, 18, mother, sister, father on Sundays), then the more subjective statements: ‘skinny, not anorexic’, ‘don’t sleep well’, ‘will study languages’. From there it spirals out and out, from the personal to the familial to the communal, the imagist word-pictures and statements becoming more and more focused on what is wrong with the whole wide world: racism, too many people, Shell, Starbucks, superficiality, sweatshops, homophobia, capitalism, waste, abuse, rape, porn, pain…

As the chalk mapping grows and grows, amendments are made, qualifiers are tagged on, new things are added (‘the Batman shooting’ and ‘Do I want children?’ and ‘I will try not to buy Coke’), and with this we hear a mix of sampled soundbites: a stock-market dealer bragging of his abilities to profit from recessions; a first-person account of genital torture; an allegation that in India people are mutilating their kids to make them more efficient beggars.

Oh, the terrible, terrible pressure of being 18 years old and feeling responsible for changing this whole wide world of injustices! Yet there comes a moment of immensely mature reflection: ‘I can’t understand everything,’ she writes.

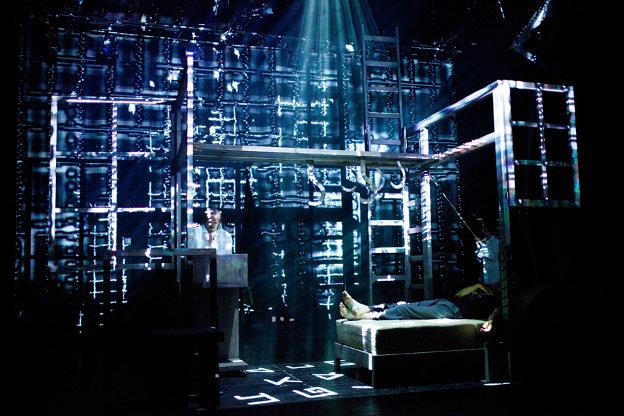

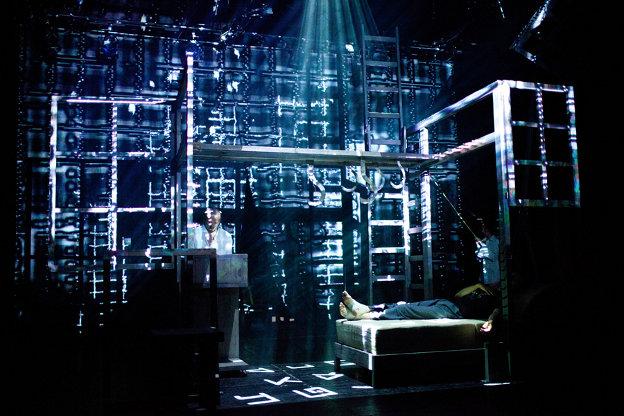

All That is Wrong is ultimately a piece about writing and about the power of words. Words surround us, chalked on the floor, written with a pen and projected via OHP onto the walls, sculpted in clanking metal letterpress forms. Words are read aloud from emails and Facebook comments, and broadcast via laptop and PA. Words pile upon words. We may not be able to understand everything, we may not be able to change everything – but through words we can understand more, change more. Here, writing is a presented as a visceral, physical activity, not merely a cerebral process.

This show is the third in Ontroerend Goed’s ‘teenage’ trilogy, preceded by Once and For All We’re Gonna Tell You Who We Are So Shut Up and Listen, andTeenage Riot, which were both presented at the Traverse in previous Edinburgh Fringe fests. It is a powerful body of work, capturing the changes through the teenage years with extraordinary precision and insight – from the just-on-the-brink kids caught between childhood toys and adult pleasures that we meet in the first show, through the ‘I want to be understood but not by YOU’ boxed-in horrors of the mid-teen years, to finally the dawn of young adulthood with a new mantra – no longer ‘you don’t understand’ but now ‘I want to understand’.

It is a pleasure to watch young writer and actor Koba Ryckewaert (who appeared in both of the previous shows in the trilogy, the youngest in the group) in her first show with Ontroerend Goed as an adult artist. Her co-performer Zach Hatch is the perfect foil, and their onstage relationship is relaxed and convivial. The piece is structured beautifully, so all credit to director Alexander Devriendt and dramaturg Joeri Smet.

As for Koba, she will write, she will write – how perfect that she finds her writing voice in public, in the Scottish venue dedicated to discovering and promoting ‘new writing’.