From Ru Paul’s Drag Race to Sadler’s Wells main stage, Dickie Beau to Thick&Tight, Lane Paul Stewart reflects on the use of lip syncing and pre-recorded voice in contemporary theatre and performance – citing his own and other artists’ experiences.

‘It’s time for you to lip sync for your life!’

These words have become quotable currency for the ever-growing fan base of RuPaul’s Drag Race since its launch in 2009. Alongside traditional drag cabaret acts, the act of lip syncing has also become more prominent within contemporary theatre making, crossing many different performative genres.

As an independent theatre maker and alumni member of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art’s MA Theatre Lab, where embodied, psycho-physical methodologies provide the framework for experimental laboratory training, I am always seeking ways to enrich my theatre practice as a process of continuous research. I experiment with the use of pre-recorded voice in my theatre practice, curating verbatim content, newsreel footage, voiceover and pop culture clippings to underscore and support live action.

Being a child of the 1980s in northern, working class England, the local video rental shop was a rich source of cinematic inspiration with the likes of The Goonies, Back To The Future, Beetlejuice, The Dark Crystal, Indiana Jones, Weird Science, Hairspray (the original) and The Wizard of Oz being watched and re-watched on numerous occasions. Mix-tape cassette recording meant I could selectively curate my own personal playlists incorporating Madonna, Donna Summer, Culture Club, Bananarama, Belinda Carlisle and Grease to shape this formative soundtrack consumed through my prized red Walkman with orange foam-covered headphones. Having the ability to stop, rewind and replay in this manner perhaps shaped the beginnings of my desire to re-experience and repurpose the voice of the ‘other’ in my work.

I am interested in the widespread use of the recorded voice and the act of lip syncing within contemporary theatre productions and events. In the realm of street theatre, Puppets With Guts’ larger-than-life illuminated puppetry act, The Lips, perform walkabout choreography, lip syncing to popular music tracks. Dance Theatre company Kidd Pivot’s 2020 production Revisor explored the relationship between language and body. Performed at Sadler’s Wells, written by Jonathan Young and choreographed and directed by Crystal Pite, the company of eight dancers perform dynamic choreography and lip sync dialogue of pre-recorded actors in this loose retelling of Gogol’s The Inspector General. At the Royal Vauxhall Tavern and other alternative spaces, cabaret sensation the LipSinkers strut their stuff…

When I think of lip syncing in contemporary British theatre, Dickie Beau immediately springs to mind. I spoke to the award-winning performer to discuss the use of lip syncing (or playback performance) within his practice. I wanted to know more about his approach as a practitioner who has been celebrated for over a decade. We began talking about lip syncing as an extension of the human urge for image replication and memorialisation, incorporating death masks, Greek theatre and the Victorian drawing room seance. I wondered what had drawn Dickie to this performance style, and who were the initial influences upon his work:

‘I met a Drag Queen called Suppositori Spelling in London, which would’ve been 2006,’ he says. ‘I think that my attitude towards lip syncing before I met them would have just been that it wasn’t really a thing or that it was about cookie-cutter drag performance where people lip sync to pop songs in a nightclub. But Suppositori Spelling was mixing up music with spoken word, usually comedy stuff like stand-up comedy material. When I saw it in action I was like, “Oh, this is more than what I thought.”’

Dickie soon became one of London’s most talked-about acts on the queer performance scene, crossing cultural boundaries, and creating both short-form cabaret-style and full-length theatre pieces as a solo performer. As we chatted, I shared my own experiences working as a solo theatre maker using pre-recorded sound as a way to incorporate additional voices into my work, both as found recordings within the public realm and recorded, verbatim interviews with members of the public. I was interested to hear how he incorporated the voices of others to share his solo stage.

‘When I lip sync I make present the idea of the person whose voice I’m channelling at the same time as I make present the fact that they are not here. And that paradox, of making an absence present, is a crackle that exists underneath the methodology.’

This notion of ‘making an absence present’ is a fitting description of Dickie’s signature style. The person speaking, the originating voice, is right there in front of you (or seemingly so), but you are also aware that they are not, a form of ‘vocal mask work’, as he puts it. Dickie’s work goes beyond creating an imitation or an impersonation of the person, there is a transformation that takes place. The audience witnesses a manifestation of the moment the voice was first recorded in the past, channelled through Dickie’s body as vessel in the present.

‘Its like a magic trick, so people forget that you’re lip syncing and then they remember, and that’s quite satisfying for an audience.’

I was keen to know about his first experience using lip syncing and how he initially approached his subject material.

‘I’d come across these tapes of Judy Garland making notes for a memoire that was never ultimately written,’ he says. ‘When I got invited to perform at an experimental performance night in East London, I returned to those tapes and it felt inconceivable to do anything with the material and not use Judy’s voice… and so it seemed like the obvious thing to do was to lip sync to the material.’

Something that struck me whilst speaking to Dickie was the intimate connection he has with the figures he interrogates (Dickie calls it ‘rememberment’). This personal connection to existing material struck a chord with my own experience re-purposing pre-recorded content. In my solo performance, Unbroken, I curated text from Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, which was recorded and used to provide a lens through which a sequence of abstract physical scores explored the notion of the confined gay male figure. I was drawn to this text through personal connection; from first reading the play in school, using the text in early career auditions and now re-experiencing the figure of Tom as a mirror of myself in the role of the ‘other’. It was an intimate investigation, providing the words I needed to say, as if they were my own. While I was repurposing the written word of Tennessee Williams, Dickie interweaves the actual voices of iconic figures from popular culture including Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe, Kenneth Williams, and Sir Ian McKellen, creating a one-man conversation around a performance’s thematic enquiry.

‘In the beginning, I had a heart connection to the material of Judy Garland and I wanted to preserve its integrity…for people to experience it directly, or directly as possible, and so it came about conceptually in a way, it was about vocal mask work.’

For Dickie, the act of lip syncing is not a superficial one of merely moving one’s mouth to someone else’s words, his process is a full-body, physically engaging act that, as with many theatrical techniques, leaves the audience believing that the performer’s actions are effortless.

‘The way, from the beginning, that I’ve worked with the voice is not really with the emphasis on the lips, but on the idea of the body being the channel for the sound. So its body syncing, really more than lip syncing, is the way I see it.’

This use of the body as a channelling vessel resonates with my own practice of generating material as a solo performer. The physical manipulation of the body (the outer) triggering an imaginative or psychological response (the inner), is a rewarding method of working for me, unearthing narratives via a process of self discovery. Dickie refers to the notion of exploring from ‘the inside-out’ when lip syncing and being ‘super present’ on stage. This echoes many traditional forms of actor training and theatrical methodology. The work of Stanislavski and the Method trains the actor to craft a world of given circumstances that is charged and alive in that particular moment; and in the work of theatre laboratory founder Jerzy Grotowski, the performer diligently and ritualistically trains the body to be as available as possible in pursuit of a passive readiness, the ‘via negativa’.

Dickie explains: ‘There is also something spiritual in the practice of doing the lip syncing, which is also ritualised, which is also about being present, so one doesn’t want to fall behind and one doesn’t want to preempt too much, so one wants to really just hover above the moment… In that process, what happens as a performer, is that one becomes super present but also aspects of oneself disappear, aspects of oneself that you think are permanent or you think are essential to you being you, they actually turn out not to be so important when you’re being present.’

My own experience of using headphone verbatim (the theatrical practice of a performer speaking another person’s pre-recorded words, directly as they hear them through headphones), came from working with Kristine Landon-Smith, theatre director and co-founder of Tamasha Theatre Company, on a production called Goodbye, whilst at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The performance was created by curating recordings of interviews with people on the subject of saying goodbye. These verbatim responses were then spoken live by the performer as the vocal recordings played in their ear. In this style of work the performer is present as a conduit, a vessel that is honestly honouring the sound without judgement or comment, allowing the words be re-experienced by the audience. Whilst Dickie is not directly speaking the words, he talks about using his whole body when performing as means to facilitate conversation between himself and the originating voice.

‘What I am doing with lip syncing as a methodology, is I am consciously trying to imagine how these sounds made by that other organism in another time, might resonate, what shapes they might make if they were travelling through my organism, or if my organism was capable of making those sounds.’

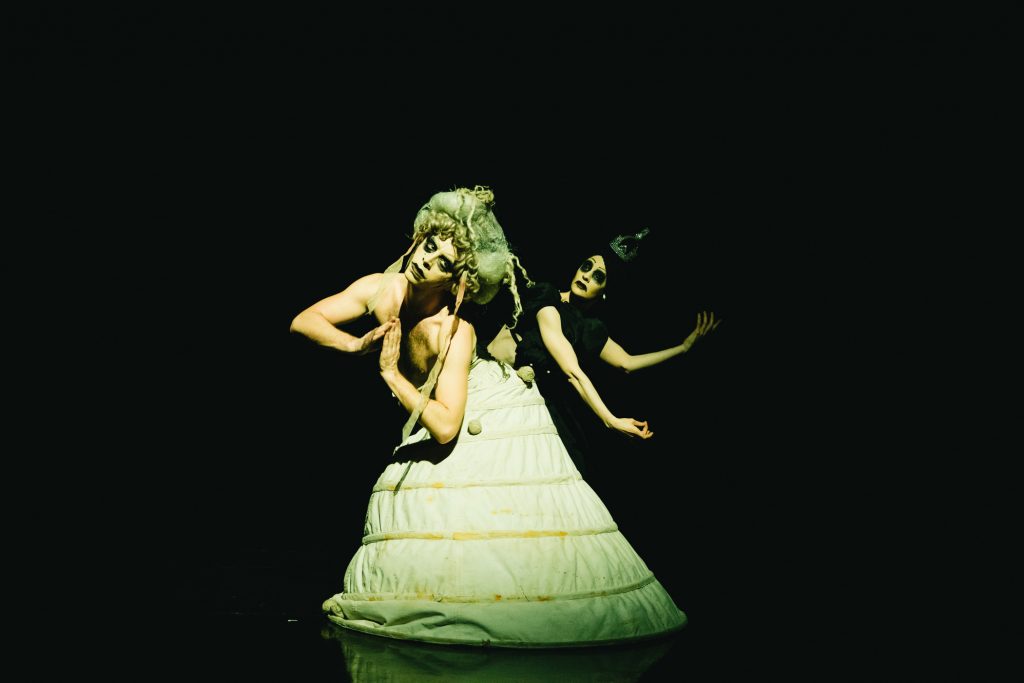

Daniel Hay-Gordon and Eleanor Perry formed the award-winning company Thick & Tight in 2012, after training together at Rambert School, with a practice that is based in ballet and contemporary dance and incorporates elements of queer performance and camp humour. At the heart of their work they continue to investigate a range of LGBTQI+ issues and figures. Their performance Short & Sweet is a collection of short form performances combining dance, drag, lip syncing and satire. One of the featured lip syncing sequences Cage & Paige: We Could Go On & On, presents the hilarious juxtaposition of vocal recordings of John Cage and Elaine Paige alongside an expressive movement score. I interviewed Daniel and Eleanor about the use of lip syncing in their work, beginning with asking Daniel how the range of voices they have used including Barbara Cartland, Derek Jarman, Elaine Paige, Matt Hancock and Prince Andrew are chosen.

‘The voices we choose normally arise from voices which surround us through what we watch, read and listen to… based on their brilliance, individuality, LGBTQI+ relevance and camp-prowess, though of course we also choose them for the opposite reasons as we love to satirise and make fools out of those who need to be taken down a peg or two! If the person’s voice has been recorded then we can go ahead, listen to as much of their performances and interviews as possible and then pull together the right sound bites for the work we want to create. If there are no sound recordings available, then we find alternative methods of translating their voice into the work such as recording ourselves speaking their work, or finding ways to embody their voice choreographically.’

With the duo being trained dancers, I wanted to continue to delve into how their physical expression meets the originating voice. Eleanor spoke about how, like Dickie, their creative process was less about the mouth (or lips) in performing the lip syncing but utilising the entire body as a means of interpreting the voice.

‘I always want to trick myself into believing that I really am the one making the sounds of the voice, that the sound originates inside me, and that way the sound feels fully connected to my body. You can feel the warmth of the voice in your chest that way. For us, this embodying of other voices has extended beyond mouthing words, and our approach to movement or dance is in a way a full-body lip sync of sound or music. This gives a connectedness and attention to the movement, which we love.’

It was clear a common theatrical language was forming from both Thick & Tight and Dickie Beau, rooting the act of lip syncing in a communion between body and voice. The performer, being fully available, becomes both vessel and conduit for the originating voice.

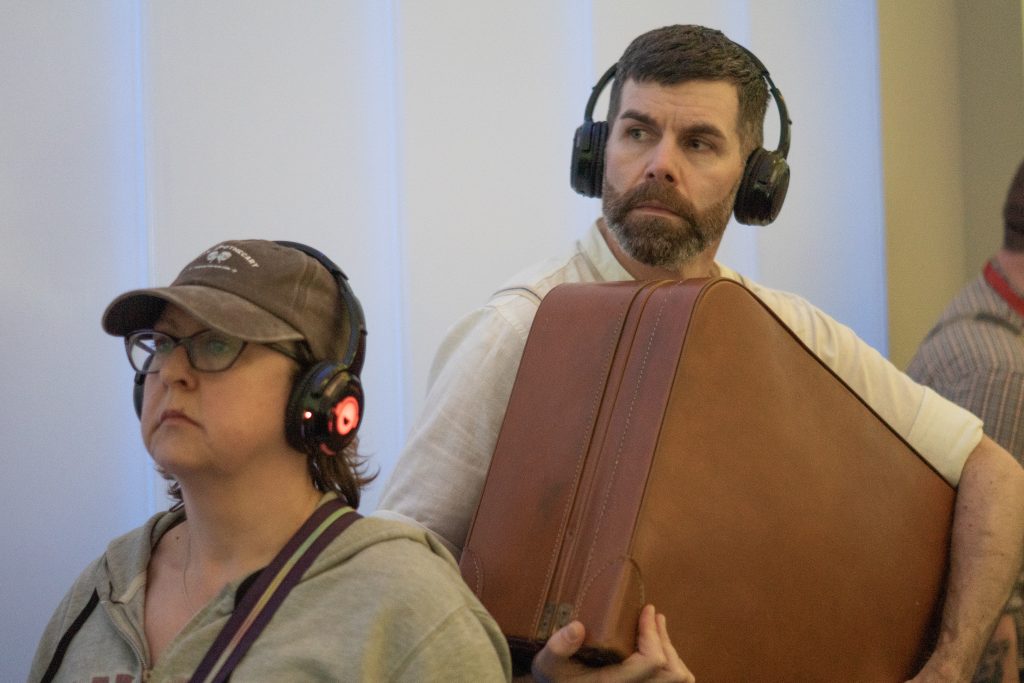

I had been wondering about the level of care and responsibility felt by artists re-purposing another person’s voice. Whilst creating a recent headphone promenade production, Seahorse, which interrogated migration and displacement, I recorded and curated interviews with members of the public whose voices contributed to a larger soundscape. I felt a weight of responsibility using these voices in the work, being clear what the voice was bringing to the performance and using the editing process with sensitivity and due diligence. There is a distinct difference in using the vocal recordings of actors or those in the public eye, who are trained to deliver anecdotes during interviews and comfortably communicate their thoughts for public consumption, and members of the general public whose verbatim recordings are often used for their honest and raw response to a specific line of questioning.

With this in mind, do Thick & Tight feel the same level of care?

‘Some of the voices we use have had to speak out in defiance and have faced abuse of various kinds because of it. I think we try to be aware of the weight of lip syncing these voices and think sensitively about how to do it. We feel a responsibility to try and do the lip sync as well as we can, to respect the art form and its place in queer culture as well as feeling a responsibility towards our audiences,’ says Eleanor, adding, ‘We would never wish to use someone for our own gain.’.

At the beginning of these conversations about lip syncing I celebrated its use in mainstream theatre but was curious what this meant for the LGBTQI+ culture it came from. As with most things brought into the mainstream from societal sidelines, they are diluted and sterilised in the process to become more palatable for a general audience. Does the ‘straight-washing’ of this queer artform represent acceptance or merely appropriation? Daniel from Thick & Tight shares his thoughts on this.

‘The mainstream appears to absorb the best of any culture and find ways to commoditise, package and sell what it has “discovered”. There are positives to this though, especially societally; it gives the masses the chance to learn and appreciate. In terms of lip syncing and the LGBTQI+ community, it is up to us to keep pushing the artform, recognising and promoting its history and not giving in to the commercial shit which dissolves great art in time.

I also asked Dickie whether using someone else’s voice in the act of lip syncing was not, in itself, an act of appropriation?

‘The decisions about what voices are being channelled and how and why, that’s all part of it, it is not absent. I think about that at every step of the way, and the decisions that I make are sometimes listening to the edges of what’s possible,’ answers Dickie. “It offers an alternative way of thinking about identity politics, for example with Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe…I wanted to in one way give them a platform but I also realised that I was identifying with them.’

The most important factor for me in this conversation is the intention and integrity of the performer. For the most part, the ‘heart connection’, as Dickie phrased it, is the driving force behind the artist’s motivation to spotlight an individual’s voice in the first place. Somehow, honestly re-encountering the words of these individuals amplifies what they represent and any satire found is in response to a point of view which is already documented in the public realm.

I believe that as an artform, the act of lip syncing goes deeper than cultural heritage and taps into the human desire to alter one’s image, wear a mask, speak someone else’s words, walk in someone else’s shoes, and ultimately foster empathy for another human being. We know that drama is conflict, and the conflict presenting itself in the act of lip syncing resides where I, the performer, ends and the other, the originating voice, begins and the ‘crackle’ or dramatic spark is that place of meeting. I have invited voices to share the stage with me to honour and respect those around me and who may have come before, each commenting on relevant conversations within a contemporary context. I wish to close with something that Dickie shared about the use of language to facilitate change in society.

‘Language brings us to a fork in the road and we can either use it to join together, to build bridges, to connect or we can use it to build figurative fences around our lives and keep people out, but we have a choice. It’s about feeling, because how are you going to get anybody to think deeply about something unless they feel something about it. Why should they bother if they don’t care?’

Featured image (top of page): Lane Paul Stewart with puppeteer Aiysha Nugent-Robinson: in Seahorse. Photo Andrew Ness

Lane Paul Stewart is a theatre maker, actor and puppeteer based in the North West of England. Following training at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), he founded Facing North Theatre and has produced work that has been performed at arts venues and festivals across the UK. Lane Paul Stewart took part in the Total Theatre Artists as Writers 2021-2022 programme.

@lanepaulstewart

Facing North Theatre has presented work at The Lowry (Salford), HOME (Manchester), Storyhouse (Chester), Bloomsbury Festival (London), Physical Fest (Liverpool), The Lucid House Performance Salon (New York). The company explores stories that investigate the notion of the ‘other’ and present these in a playful manner, probing the boundaries and spaces of theatrical presentation. This includes site-specific projects that challenge an audience’s perception of traditional theatre spaces. Productions include; Seahorse (2019 & 2022), To Equality & Beyond (2019), Dyschronometria (2020), Unbroken (2020 & 2021)

@facingnorththeatre

Dickie Beau is a pioneer of playback performance, emerging from the drag tradition of lip syncing. His work is increasingly studied on contemporary theatre and performances courses in the UK and has received multiple awards across a range of performance disciplines. Dickie recently worked as a consultant to Renée Zellweger and Rupert Goold on the feature film Judy. He is an artist supervisor for a PhD research project at Norway’s Academy of Music in Oslo and an artist advisor for the Jerwood Foundation. Productions include; Re-Member Me (2019), Blackouts: Twilight of the Idols (2011), Dickie Beau: Unplugged, Camera Lucida (2014).

Thick & Tight are an award-winning dance theatre company based in the UK who create a mix of dance, mime, theatre and drag, taking influence from a wide range of historical, political, literary and artistic subjects. Internationally their work has been presented at a variety of arts festivals including Stockholm Fringe (Sweden), Klovnbuf International Festival (Slovenia), Sydney Fringe (Australia) & Lucky Trimmer (Germany). The duo often work with students, teaching, lecturing and choreographing new work which reflects their artistic research & interest in the potential of dance as a political art form with the power to create positive social change. Productions include; Short & Sweet (2022), A Night With Thick & Tight (2018), Romancing The Apocalypse (2019).