First came the whistles, then the drums. Seven assorted-size dancers marched through the foyer twirling batons, looking very pleased with themselves in orange majorette outfits and unnecessarily high furry busbies. Cameras flashed as coats and drinks were gathered up and a happy throng followed them into the auditorium. Pity the poor folk in the upstairs seats who missed a great opener; lucky us in the stalls.

Decouflé is a master of the big stage picture. He has shown his versatility and range in the opening and closing ceremonies for Albertville Winter Olympics (1992) and more recently with Iris for Cirque du Soleil. His defining show Codex (1986) launched his career as a choreographer with an exuberant visual awareness and curiosity; since then his use of video has become one the defining characteristics of his performances.

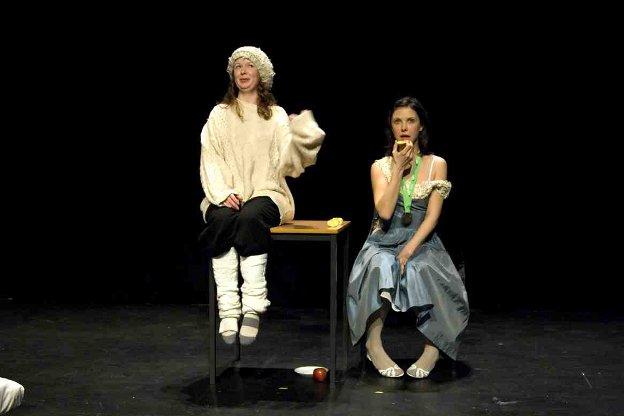

For Panorama, Decouflé goes back to basics. He takes some very early works and re-stages them with a new company, different costumes, and a fabulous range of music created by six composers. It is episodic, much like the circus he so loves, and overseen by a Master of Ceremonies – Matthieu Penchinat.

The stage set is a big arching grid, a visual echo of tent frames, with the dancers changing in the wings by fairy lights. It’s informal, unpretentious and playful. There is so much variety of movement and style it is hard to pinpoint a ‘signature’ choreographic approach, other than to say it is sinuous, acrobatic and quirky with often gravity defying leaps.

Stand-out moments include a fantastic riff on computer games with human sound effects, a beautiful and funny aerial duet on bungies, and a heart-stopping solo by a dancer in huge antlers.

There is exquisite use of shadow puppetry melding into life-size cartoon characters and an all too brief taste of Codex with its surreal mutant beings.

Panorama ends with a tableaux of the company clicking imaginary castanets to Orlando’s Hideaway. The precision is absolute, the costumes (Philippe Guillotel) are again shades of orange; it is simple and sublime.

If Vague Café, for which Decouflé won the Bagnolet competition in 1983 and which has not been re-staged since, seems tame thirty years on, there is much to celebrate. I missed the film wizardry a little, but what a journey he has had and what a joy for an audience to see these re-envisaged pieces.