Toxic or what? Tom Brennan – director, writer and co-founder of The Wardrobe Ensemble – muses on fragile masculinity in art-making

When I was a teenager, I was, quite frankly, a brilliant actor. And I bloody knew it.

I was excellent in the way that teenage boys are excellent at acting. I was brooding and intense. I didn’t have any qualms about shouting very loudly or leaving pauses far longer than my peers. I was good at accents, and could look into the lights for a while and make tears appear in my eyes. I loved it and took it seriously. When rehearsing a scene from Harold Pinter’s One For The Road, it was a thrill to sit in my dark bedroom and imagine that I had tortured a family.

As a pale teenage boy with little-to-no athletic or sexual prowess, I look back and see that the black box drama studio was a fundamental space in forging some kind of masculine identity for myself. It was not on the football pitch or at the drunken party, but here that I commanded space and had power. Here, I was a man. And I wonder if I wasn’t alone in the nature of my theatrical baptism.

These days, I work mainly as a director. I think I’m a lot less intense than my teenage self. The more I work with different kinds of performers and artists, I’m aware that I don’t want to dictate their process. ‘Whatever works’ seems to be a good motto when leading a room. For example, if you need, as someone I worked with famously did, to wash your balls before and after performing the show, that’s A-OK by me. Please wash on. But perhaps there are limits. A few years ago, as an assistant director, I remember working with a talented and very successful young actor who would scream and bash his head against a wall until he felt ready to access the scene. And so, I’d also like to call something out, which I often see in younger actors, but which I also see across the arts. A trait which for now I will call ‘The Curse of the Serious Artist’.

In an article for The Chicago Reader (8 June 2016), Aimee Levitt and Christopher Piatt outline the abuse that took place at a local theatre company, on stage and off. The Profiles Theatre were known for what The Chicago Sun-Times would refer to as ‘knock-em-dead’ revivals of American plays. Their ballsy motto ‘whatever the truth requires’ gives an indication of the kind of work they made. Their standout production of Tracy Lett’s dark and violent play Killer Joe was no different, a show which one blogger excitedly described as ‘vicious and real!’. But what wasn’t understood by critics at the time, was that the co-artistic director and actor Darrell W. Cox (who played the titular Joe in their production) was literally beating people up on stage every night. Levitt and Piatt write, ‘The reason Killer Joe felt so vicious and so real was because it was. All of it: the choking, the bruises, the deep-throating of a chicken leg, the body slam into the refrigerator.’

Whether Cox should be deemed a psychopath or a dedicated artist is one question (the answer for me: a definitive psychopath). But the more difficult question is, Why did so many of his colleagues accept this behaviour? It seemed his acolytes accepted their working conditions not just because Cox was psychologically manipulative, but because the culture of Serious Art-making legitimised the abuse. ‘Whatever the truth requires’ was an ethic that the entire group signed up for and believed in.

What’s particularly sad about the case at Profiles Theatre is the sense that everyone wanted to make good art. They took it seriously. But unfortunately, the parameters of what that meant exactly, and how to get there, were terribly skewed. Any voice of dissent was framed as cowardice, as someone just not willing to ‘go there’. And although this case is extreme, I’d posit that similar cultures of art-making are not rare.

I am reminded of the notorious ‘living theatre’ module at a certain prestigious drama school. Acting graduates, in whispered tones, have described to me the week they spent living in ‘the Irish potato famine’ (on the outskirts of Epping). The idea is to stay in character for a whole week, to connect to the reality of some lived, historical experience. One actor told me how she’d spent a week in silence, simply digging graves. Another told me how halfway through the week, she was ushered into a room with her teachers and told that she (her character) had just been raped. Another actor played a sadistic English soldier and spent the week bullying his classmates.

There’s something, for me, vaguely humorous and absurd about this module. But I also find its pursuit of lived ‘truth’ a little troubling. As if a week spent on the grounds of a drama school in Essex has anything to do with the lived experience of the potato famine. And importantly, to what end? Presumably, so that actors might then perform for an audience a play about the potato famine with a level of meticulous, terrifying, semi-starved detail. When we stop to think about it, it seems a very weird ambition.

If we are pursuing big words like ‘truth’, ‘lived experience’ and ‘reality’ with such intensity and seriousness, it seems also useful to ask ourselves two simple questions: Why? And, is it worth it?

It’s the same attitude that awards Best Actor Oscars for unhealthy weight gain or loss. It’s the attitude which, on the set of dire superhero film Suicide Squad justifies Jared Leto sending his co-stars dead pigs, live rats and used condoms when ‘preparing’ for his role as comic-book villain The Joker. Go Jared!

More commonly, the approach seems to connect to the ways we as audiences fetishise certain roles and expect actors to inhabit them. Every semi-famous male actor needs to do their Hamlet, like it’s a rite of passage. ‘It is my time,’ they say. The audience attending is perhaps less interested in being moved, in having a surprising theatrical experience, than they are in seeing the effort of the task being attempted. Can the man do the Hamlet as well as the last man did the Hamlet? Can they fuck the Hamlet with the effort that is required? Do they have the superior emotional, intellectual and physical agility and power? The show becomes, then, a flexing of muscles. And though this isn’t as dangerous as the abuses at Profiles Theatre, the philosophy is connected.

I think it’s a problem triggered by fragile masculinity.

Here’s my theory: that many men feel a bit weird about the fact that we’re artists and that we’re not doing ‘a proper job’. Not only are we actively told that it isn’t a real job (because my ‘next job is in cyber, I just don’t know it yet’) but also, sometimes, our job is quite fun. Rehearsals are fun. Making things is fun. And so, when we see people with boring, difficult and physically demanding jobs, we feel guilty and embarrassed.

It’s much more comfortable for us to feel like we’re doing the important act of ‘finding the truth’ at whatever cost, than something more ambiguous: telling a story, making a show, entertaining people, giving people something to respond to.

If, like me, ‘theatre-men’ for want of a better term, found their masculine power in an artistic space, rather than a space traditionally associated with men, it makes sense that we want to re-make that space into something that feels valid and important. We want it, at some level, to resemble the spaces that we associate with conventional male power and work.

And of course, it should be noted that this is not just a straight, white male epidemic. I’ve heard many stories of theatre directors of every ilk who didn’t feel a day was worthwhile until every actor cried.

And so, not only does the culture of art-making change, but the language does too. When working professionally (and particularly in training environments), we often talk about ‘serious’ art-making through the language of the fight. We like the idea that art-making, and therefore good art, is brave, uncompromising, brutal and intense. Perhaps it is at times. It’s certainly brutal not knowing where your next gig is coming from, or how you’ll pay your rent when the Arts Council money dries up. But the opposite language sounds sacrilegious. To suggest a piece of work is ‘fun’ sounds insulting. ‘Fun’ suggests that the person making it didn’t care and that their ambitions for the work were low.

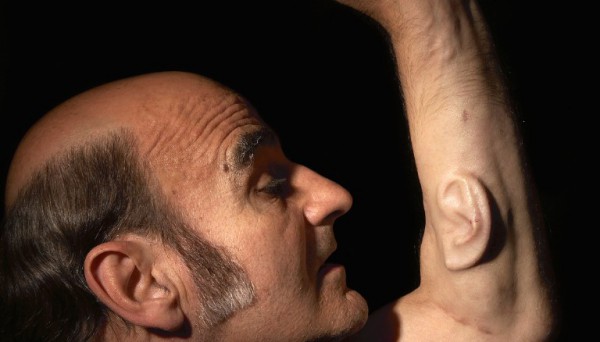

Although I think this kind of attitude is particularly visible in relation to dramatic acting, the same can be found in any kind of artistic practice. I was recently introduced to Australian performance artist Stelarc’s work for example. He uses the body as a site for exploration and exhibition, often dealing with the idea that ‘the human body is obsolete’. I find the issues discussed in his work incredibly powerful. For example, in 2015 he grew an ear on his arm using stem cells. What’s not to love? But in large parts of his work, where his and other participants’ bodies are suspended above the ground using hooks that pierce their flesh in several places, I wonder if something similar to ‘macho acting’ is going on beneath the surface.

I don’t want to question the ethics or intent of the work, i.e. Stelarc’s choice to be pierced, or an audience’s choice to witness the mutilation. But, does Stelarc want to prove how intense and dedicated to Serious Art-making he is by poking large hooks in his body? Therefore, do we as audiences respond to his dedication more than the work itself? Much like Jared Leto sending dead pigs to his co-stars, there is, perhaps, a gesture in his work that wants to show us his muscles.

I feel reactionary and prudish when attempting to critique performance art and indeed any art in these terms. But how strange that I do! As though in critiquing the idea of Serious Art I am not rising to its challenge. I am stood at the side of the boxing ring, attacking the brutality of the game out of fear for my own face. The fact that I feel nervous to even discuss it is an indication of its ingrained power.

But there are, of course, approaches to work that sit against the Serious; that are by their very nature ‘fun’. These are forms which might be quite familiar to the readers of Total Theatre Magazine: clowning and play. This is art-making which is rich and rigorous, but also seems encouragingly ‘anti-Serious’. For example, let’s take the clown guru Philippe Gaulier. In John Wright’s glorious feature for Total Theatre (Issue 3-1, Spring 1992), Gaulier says, ‘We want to see actors enjoying themselves. We are not interested that you have just buried your grandmother.’ Take note, drama schools. Wright describes how Gaulier ‘wants actors to respect each other on stage, to allow each other scope to reveal their soft underbelly’. Now, I’m a little bit suspicious of the way that Gaulier’s training is described by its graduates. At his school in Paris, students perform for their maestro daily and are then subjected to a barrage of insults. As Phil Burgers, best known for his anarchic alter-ego Doctor Brown, says in an interview with Brian Logan (the Guardian, 2 August 2016): ‘I had moments of extreme suffering there.’ Again, it seems, we’re back in the territory of macho can-you-take-it art-making. But I’m also encouraged by Logan’s take: ‘No one seems intimidated by him… it’s a kind of game.’ There is a sense here of intensity without suffering. A self-awareness that sits against the machismo of so much of traditional theatre-making culture.

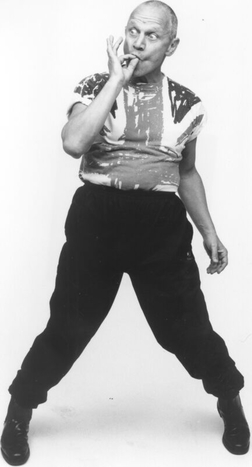

But these forms too, may be easily clogged by the blight of serious machismo in other ways. Take Steven Berkoff as an example. I remember pissing myself with laughter during his performance of Dog, a deliciously silly show with a silly conceit, performed with precise silliness. One might assume that the artist who would make such a show might be a lot of fun. But he’s notoriously bullish as a collaborator and director. His rage is the stuff of legend. And this combative sense rubs off on the way that we discuss and think about him. In John Freeman’s article for Total Theatre (aptly titled ‘Battling with Berkoff’, Issue 15-4, Winter 2003), he describes his subject as ‘hugging the corner of the room like a between-rounds boxer’.

And so the question once again becomes, How much of the ticket is not to see a Berkoff show, but in fact to see The Original Nightmare Arsehole? Like he’s some damaged and dangerous animal.

I don’t want to knock work with serious intent, with rigorous working methods or with a dark, uncompromising tone. But it feels important to question where the focus of the artist is, and also importantly, where the power of the work lies. There’s no real need for us to equate difficulty with quality. There’s no need for us to equate intensity of process with excellence. So it feels important that we think critically about the measures we use when we discuss the work of other artists. Though it often feels like a competition, what makes art-making so brilliant is that it isn’t a combative endeavour.

In this Covid-enforced hiatus from the rehearsal room, I’ve been reflecting on my artistic process and the times that I’ve suffered from ‘The Curse of The Serious Artist’. Which moments in the rehearsal process have I felt the need to perform my dedication to the work? How often have I unnecessarily given myself and others a rough time? How many times have I equated shouting and swearing with directing? Or even more simply: long, long hours with productivity?

But there’s a competing emotion I feel in these strange times, one that’s not very helpful and doesn’t make tremendous sense. Perhaps if I had been more of a serious artist, if I had cared more, done more, fought harder, then I’d feel more stable. And importantly (because it is so important that we search for ‘the truth’, whatever that means) now that my work has been taken away, am I really a man? (The answer is probably ‘stop being an idiot.’)

Though I don’t have any earth-shattering conclusions, it feels important to address these questions, because if we’re interested in redressing gender imbalances in rehearsal rooms we need to analyse the cultural assumptions that we bring into our processes. Yes, we should think about the quantity of men in the room and the volume of space that we take up. But equally, if we want real change to take place, we need to examine the nuances of the way that we decide to take up that space.

At this moment, when most of our professional work is paused, the ways that we normally define our identity and self-worth are also on hold. And so, for the health of ourselves and our industry as a whole, we should use this time to re-evaluate and perhaps re-define what it is we value and how we wish to define ourselves (whether in relation to masculinity or not).

So, to both ‘theatre-men’ and/or ’serious artists’, my hope is that we chill-out. Perhaps we need to, in whatever (creative?) role or project, embrace our inner clown. My hope is that when we can graduate from the insecure mentality of performing our power, justifying our work through our own suffering (and the suffering of our colleagues), is when we can stop masturbating and start making art.

Featured image (top): The Last of The Pelican Daughters at Royal and Derngate Theatres, Northampton. Photo by Graeme Braidwood

Tom Brennan is a director, writer and co-founder of The Wardrobe Ensemble. www.thewardrobeensemble.com

Their production of The Great Gatsby can be watched here through March 2021: https://thewardrobetheatre.com/livetheatre/the-great-gatsby/

Tom took part in the Total Theatre Artists as Writers Programme 2020.