A chorus line with wolf heads and cartoon gartered legs; a dazzling psychedelic explosion of flowers, fairies, and butterflies; and Terry Gilliam-style cog-filled heads. Chinese dragon-serpents chasing their own tails; spear-carrying monkeys; and an aria-singing spider woman.

Welcome to the crazy world of Komische Oper Berlin’s The Magic Flute.

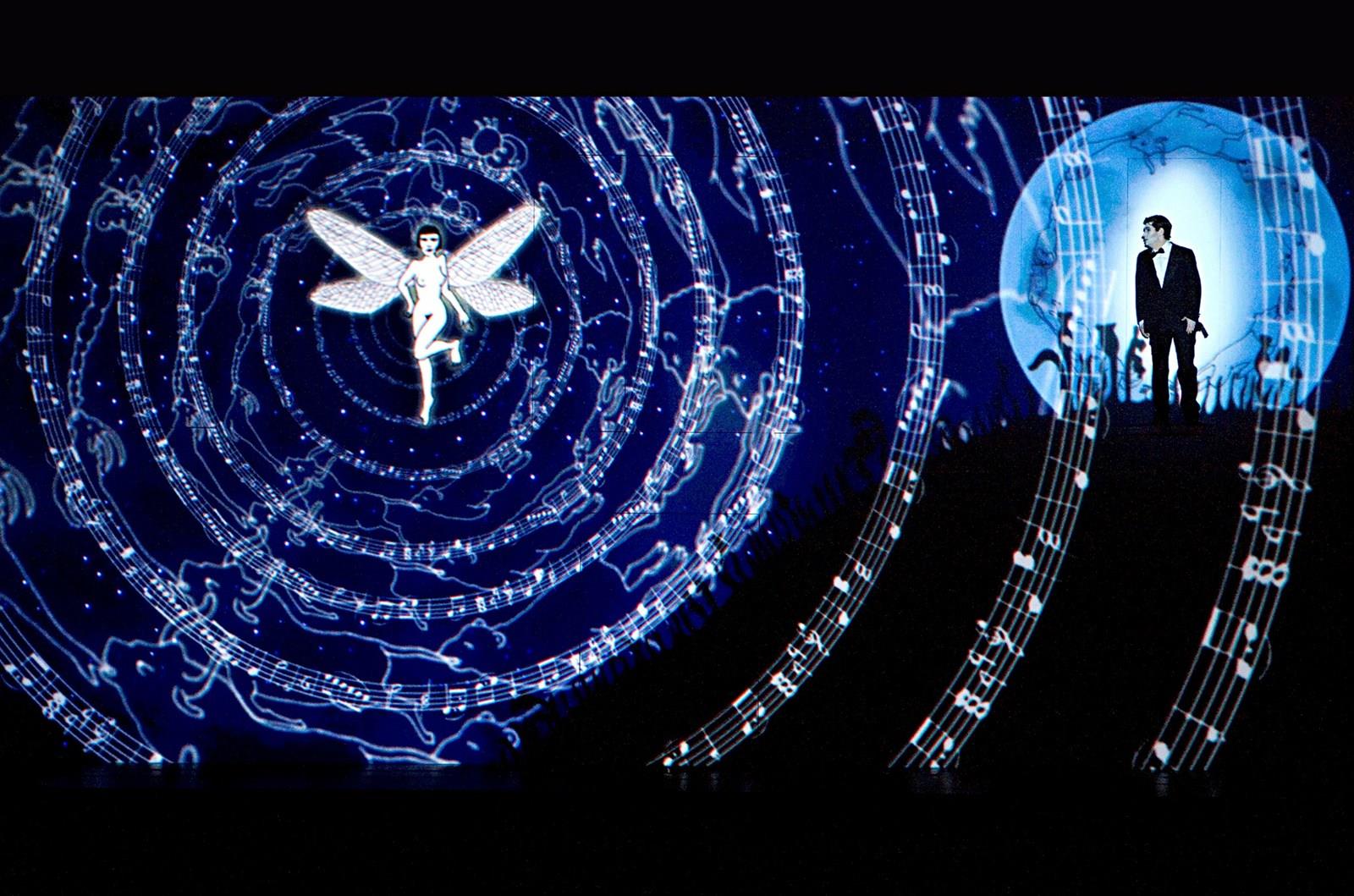

Co-directed by Barrie Kosky and 1927 theatre company’s Suzanne Andrade, with animation by 1927’s Paul Barritt, the work bears the immediately recognisable signature of that enterprising company’s work. A magical blend of live and screen action, the performers interacting with surreally funny animation, so that they become part of a live comic book; silent-movie style titles, replacing dialogue with beautiful black-and-white graphics; and a countless number of nods to the 1920s Hollywood heyday, with homages to Buster Keaton, Nosferatu, and Louise Brooks built in.

It is almost three hours (with one interval) and it is both exhilarating and exhausting. Paul Barritt excels himself with animation sequences that at times make your eyes ache; and the stage is agog with opera singers fighting off shadowy wolves, popping their heads through holes in the screen to sing perfect top ‘c’s, or donning beards and dashing up to the boxes to sing the choral parts.

I’m no opera expert, but I know that Die Zauberflote / The Magic Flute is Mozart’s last great work; that its bizarre and incredible (even to fans of fantasy) storyline remains a puzzle; and that it is often played with vaudevillian pizzazz. Although perhaps never more so than in this case. The music sounds fine and dandy to my untutored ears, with Olga Pudova impressive as the Queen of the Night spider woman, Dominik Koninger a winner as the Keaton-esque Papageno, Allan Clayton doing a great job as the pale-skinned kohl-eyed Tamino, and Brooks/Andrade lookalike Maureen McKay rising to the demands of a very physical rendition of her role as Pamina.

The story is so batty it hardly bears telling: a daft and convoluted fairy tale of lost voices, magical musical instruments, and trials of temptation, which features a lost prince, a bird catcher, a giant serpent, a witchy Queen of the Night, and various lost and found loves. But no one cares how silly it all is – in fact, this is celebrated in a production that exploits the ludicrous possibilities the bizarre imagery of the libretto offers. It also tightens up the stage action by replacing dialogue with titles.

The interaction between live and screen action is understandably far less sophisticated than in 1927’s own shows – these are opera singers, not physical theatre performers – but there are clever shortcuts and tricks to show them to best advantage. And of course, no expense is spared. This is opera budgets, not experimental theatre, we’re talking.

There are criticisms, from the perspective of someone who has followed 1927’s work since they won the Total Theatre Award for Best Newcomer at the Fringe a mere eight years ago. I don’t feel that comfortable with the company cannibalising their own work. Or perhaps it is director Barrie Kosky who has encouraged them to do so? In the programme notes he declares himself a fan of their first show, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.

I find it uncomfortable seeing imagery from that show and its successor, The Animals and Children Took to the Streets, regurgitated here. For example, the image of Papageno running on the spot with cartoon animation legs is a direct lift from the image of Esme Appleton doing that very same thing at the beginning of Between the Devil. And the wolf-dogs, cats, moon rising over the roof are familiar. The chorus of women looking just like Suzanne Andrade’s character in the first show is surreal, and not necessarily in a good way. Perhaps the company would argue that these are visual motifs that they choose to repeat from show to show – and fair enough, close on three hours is a lot to fill!

But I’m personally much more comfortable when the imagery moves clearly into new territory unique to this production – and there are some staggeringly wonderful things. Gorgeously drawn tarot cards, knife-throwing spiders, flowers that sprout heads, exploding hearts, steampunk elephants, whirring insects… the images tip out one after the other. The one animation sequence that confuses me is the Pink Elephants on Parade homage to Disney’s Dumbo. It’s clever – but hard to understand what it is doing here.

And I have to say that whilst I commend the company taking up offers to move into new territory, I really do miss composer/musician Lilian Henley’s lovely presence. The production is on one level very 1927 – but on another level, it feels incomplete, and occasionally a pastiche of itself. I suppose that’s because the extraordinary vision of 1927’s three shows (the two previously mentioned and current touring production Golem) comes from the unique combination that is made by all four of the core company members working together, and the input of regular collaborators such as costume designer Sarah Munro (from The Insect Circus – a lot of her influence is evident here too). Or is my slight discomfort something to do with being in on something at the start and being startled by seeing it go mainstream? I will own up to a little of that too…

Yet still – an extraordinary and dazzling production. It all goes with a swing, and the packed audience at the Festival Theatre for the Edinburgh International Festival opening frequently bursts into spontaneous applause, rising to a standing ovation at the end as the company, directors, animator, and conductor take numerous curtain call bows.

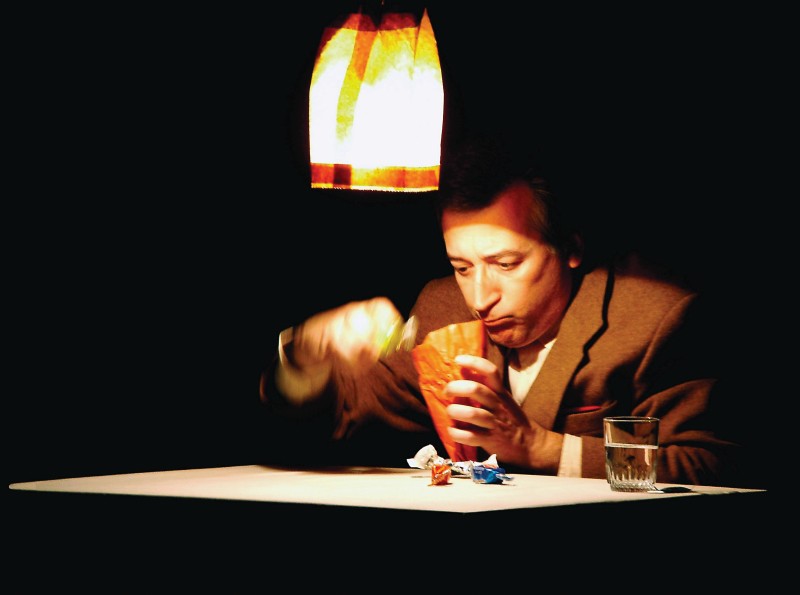

Almost without being noticed, an unassuming elderly man crosses the stage and starts addressing us in a thickly evocative Spanish accent. Carles Cañellas tells us that Small Suicides was made in 1984, that he saw it performed by its Hungarian creator, Gulya Molnàr, several times, and that Molnàr gave him permission to take it on. While he’s talking, he removes his jacket and shoes carefully and deliberately and puts on another pair of shoes and another jacket. It’s considered, precise, the objects telling the story with him: Cañellas literally steps into Molnàr’s shoes. It’s a lovely way of framing this charming and eccentric piece of performance-philosophy, priming us for a show concerned with mutable identities and what it means to take on a life.

Almost without being noticed, an unassuming elderly man crosses the stage and starts addressing us in a thickly evocative Spanish accent. Carles Cañellas tells us that Small Suicides was made in 1984, that he saw it performed by its Hungarian creator, Gulya Molnàr, several times, and that Molnàr gave him permission to take it on. While he’s talking, he removes his jacket and shoes carefully and deliberately and puts on another pair of shoes and another jacket. It’s considered, precise, the objects telling the story with him: Cañellas literally steps into Molnàr’s shoes. It’s a lovely way of framing this charming and eccentric piece of performance-philosophy, priming us for a show concerned with mutable identities and what it means to take on a life.