I came home from the play and looked out my copy of the novel. It is hard to believe how yellow the pages have grown – more brown towards the edges. The glue in the spine has become brittle, so the book can only be opened with great care, and probably not with a view to reading the full text again. That would demand a new copy.

I came home from the play and looked out my copy of the novel. It is hard to believe how yellow the pages have grown – more brown towards the edges. The glue in the spine has become brittle, so the book can only be opened with great care, and probably not with a view to reading the full text again. That would demand a new copy.

But the work of time is, in this case, largely immaterial. The book was internalised long ago. For those of us coming of age in 1980s Scotland it was, to some extent, as much a life saver as a game changer. The appearance of Lanark was big in every sense. It was a door stopper of a tome, and once opened it fizzed like a new bottle of Strathmore, frothing with playful intellectual vigour, unhinged flights of fancy, typographical ellipses, polemical heat, and, above all, craft.

In an otherwise antipathetic culture a young generation of Scots were shown in these pages how the voice of the artist, however personal, doubting, obsessive or tortured could and should be considered as a strong and positive force within the fabric of a healthy and coherent society.

Many of those involved with the staging of Lanark were part of that generation and there is much in Citizen Theatre’s ambitious (could it be anything else?) and exuberant (again, could it be anything else?) production that presents as a playful and affectionate tribute to Alasdair Gray himself – not least of which in the double-take doppelganger impression of the author provided by Communicado’s Gerry Mulgrew.

Writer, Director, and Composer roles are taken up, respectively, by Suspect Culture founders David Greig, Graham Eatough, and Nick Powell. And while it’s easy to imagine that Greig must have been as much terrified as thrilled at the task, Eatough and Powell have tackled the steep challenge with gusto and a great deal of style.

Three very different stylings have been adopted for each of the acts that chart the parallel lives of Lanark, a lost soul seeking cause and reason in a dystopian, daylight-starved city that just might be Hell, and Duncan Thaw, a boy growing towards what he perceives to be his destiny as an artist in post war Glasgow.

The first – well, Act 2, actually – is perhaps the most hesitant. Set largely in the Orwellian Unthank, the surreal, nightmarish styling is filtered through a lens of Glaswegian jazz and a certain panto-style delivery that often stops one cry shy of ‘fandabidozi.’ Special mention has to go, on that front, to the beautiful comic turn of George Drennan. Himself no stranger to the Scottish pantomime having played the villain in numerous seasonal Tron productions, his characterisation of the lift that whisks people through the multiple departments of the sinister Institute is high camp incarnate.

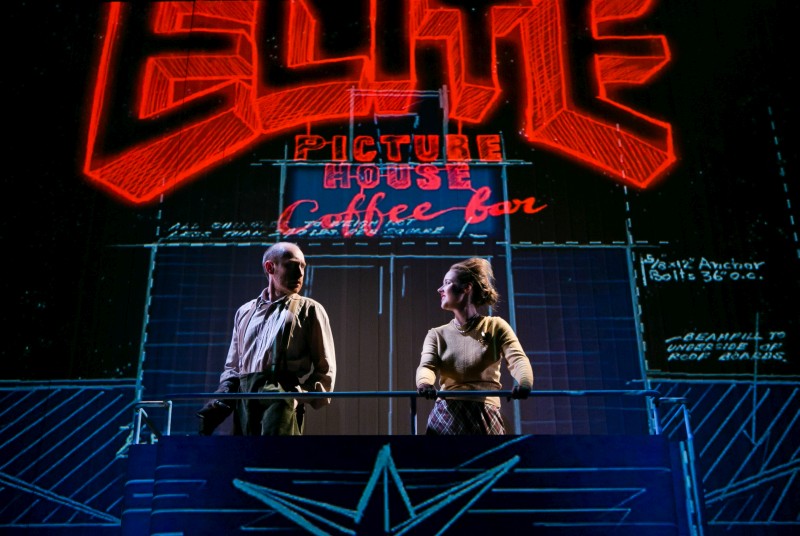

In the second act – Act 1, actually – the approach is much more austere, with the 10 performers making maximum use of a minimal, sketched scaffold and some incredibly taut writing from Greig.

Whereas in the book, much of this period addresses the artistic, political, and societal awakening of Thaw, as much as a young man’s struggle to understand the biggies of time, mortality and love, Greig has tended to focus upon sexual awakening and the adolescent waypoints of lust, infatuation and rejection.

The third act – indeed, it is Act 3 – is really where this epic gets into its stride. One gets a palpable sense of the entire company relaxing and beginning to play with the material – the way it was probably meant to be. It begins with a curtain call and ends with Gray’s signature ‘Goodbye.’ What we have in between, despite an occasional clumsy reference to 80s fashion and electronic music, is a bravado display of theatrical confidence and imaginative flow.

Lanark, in Sandy Grierson’s poised, balanced performance, embracing both the obstinate and the vulnerable in equal measure, movingly reaches some kind of contentment having realised that ‘without death, even love turns to farce.’

The postmodern games of the original text translate to the stage with the breakdown of scenery, the appearance of technicians, line prompts, a copy of the novel, the author himself and – beautifully – an interview with the author which we view from the inside of Gray’s own head and which leads to a re-write in the working script (‘Is this an adaptation? Well, fucking adapt!’). The whole thing becomes so beautifully cluttered, chaotic, and messy that even in the closing seconds of fire and flood one wonders what new inventive twist might arise from the turmoil. In this respect it is most faithful to the book.

Lanark: A Life in Three Acts plays as an affectionate, moving, and gutsy tribute to a man and his work from a generation of artists, writers, and activists who internalised that immense book and, from it, found their own way.