This year marks the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic, an event that continues to reverberate as an archetype of tragedy and disaster. But despite being very old news, the sinking of what the White Star Line billed as its biggest ‘super-liner’ captures the public imagination as if it happened only yesterday. In association with Aspire Trust and in the awesome setting of Liverpool Cathedral, Cut to the Chase Productions has produced Treasured, an immersive site-specific performance that offers a way of discovering the history of the Titanic while providing the space to commemorate and mourn its victims.

An indoor performance setting more immense than Liverpool Cathedral is unlikely to exist. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s building is dramatic enough on its own terms, so it is little wonder that director Jen Heyes was attracted by the vast potential of the space as a blank canvas for a multimedia performance. My journey began in the relative intimacy of the Lady Chapel, in which a girl dressed in the style of a crew member kindly invited me to ‘Enjoy your journey’. The historical irony of this phrase resounded as I walked around a tableau vivant featuring Nick Birkinshaw as ‘Artefact Man’, who sat amongst archive boxes scanning documents onto an iPad. Brendan Ball’s live trumpet solo – a kind of fragmented, atonal Last Post delivered from a balcony – left little doubt that Treasured was going to be a mournful traversal of its subject.

We then ascended slowly into the Cathedral proper. Barely visible in the rich darkness, performers from Aspire’s Ensemble dressed as Edwardian figures watched over us silently as we made our way. The sense of something being held back from the brink created eerie tension: at any second those figures might have addressed us in speech or emitted sound. But it was during my procession up the North Choir Aisle that Treasured’s nature as a site-specific performance came into focus, since it was impossible not to view the Chancel as the inverted hull of a ship. Along with the masses of plastic sheeting, spilling out of the building’s corners like water suspended in time, this conveyed the suggestion of history having gone awry. Like anyone peering into the wreckage, we traipsed our way through the ruins in order to make sense of it all.

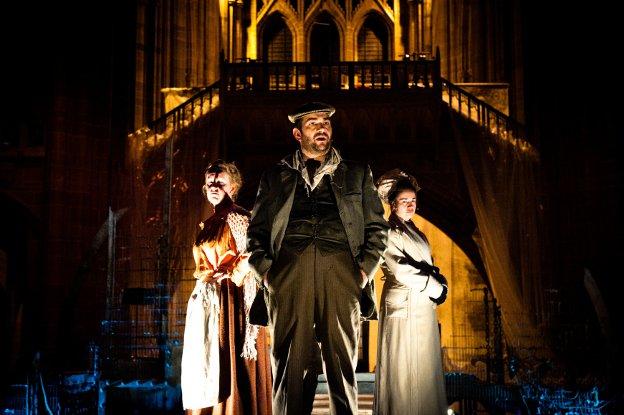

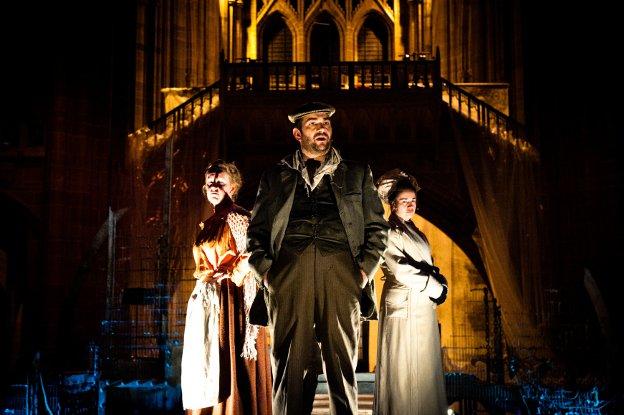

Our journey around the tableaux prepared us for the main performance in the Central Space. Banks of seating were surrounded by a stage comprised of a ship’s funnel lying prostrate; in its sculptural deterioration it resembled the carcass of a whale – indeed, as one repeated line put it during the performance, the Titanic was a ‘leviathan of the seas’. Despite its potent imagery and mixed dramaturgy (notably in the form of aerial dance from Wired Aerial Theatre),Treasured then had little option but to trace a linear narrative in naturalistic terms. This through-line, though, was interrupted by multimedia elements that tugged at the fictive nature of performance by reminding the audience of the archive’s presence. Illuminos, a company focusing on large-scale projections in the public realm, created abstract designs that harmonised well with Heyes’ imagistic-cum-naturalistic direction to form a critical representation of the Titanic story. Resisting a total immersion in the past or the present, the performance moved fluently between the two to orchestrate precisely this outcome.

‘We need the work’: these words, delivered by an implacable Scouser, opened a bracing exchange with a Belfast docker about whether Liverpool or Belfast was the city to build the Titanic. It was difficult in this moment not to think differently about the relationship between Liverpool and Ireland – perennial reflections on which course through the city’s lifeblood – or to consider the shrewd priorities of the city’s historic docklands. Liverpool in its broadest sense was absorbed into the performance site.

Before its maiden voyage, the Titanic inspired dreams of plentiful labour for a docklands workforce always desperate to earn a living. This is why our sympathies rest with Hollinshead’s docker, who spun the idea of Belfast building the Titanic into a paean of working class pride and symbol of a brave new world of technological progress and mobility. His wife touchingly held her husband’s dreams in check while loving him for dreaming in the first place. A maid from the West Country named Lucy was a doughty and sensitive working class woman yearning for a better life. With the news that Lucy survived the disaster but that ‘the Titanic had taken her tenacity’ comes the rueful acknowledgement that the super-liner’s after-life was disastrous in its own way for the survivors too.

Treasured was concerned with class critique and the internationalism of its passenger list, a number of whose names were called during the performance in the manner of official mourning. The history of the Titanic is world history. It is therefore unsurprising that the performance’s theme revolved around the merciless objectives of capitalist hubris, a point made startlingly clear by the repetition of the phrase ‘first class’ on the plans of the Titanic, projected in motion onto the Cathedral’s walls by Illuminos. Towards the end Treasuredmade a similarly eloquent statement about the inescapability of history when the projection of passengers’ names settled into an image of the offices of the White Star Line in Liverpool, a building still in existence today. Respectfully lifting the lid on the archives for dramatic purposes, Treasured demonstrated that unlike the physical ruins of the super-liner, this history will never be laid to rest.