Cuckoo! Here they come, the Cuckoos – red and white and shiny, rolling along the conveyor belt as a cheery jingle sings out. What is a Cuckoo? It’s a rice cooker – the brand so popular in Jaha Koo’s homeland, South Korea, that Cuckoo is to rice cooker there as Hoover is to vacuum cleaner here in Britain.

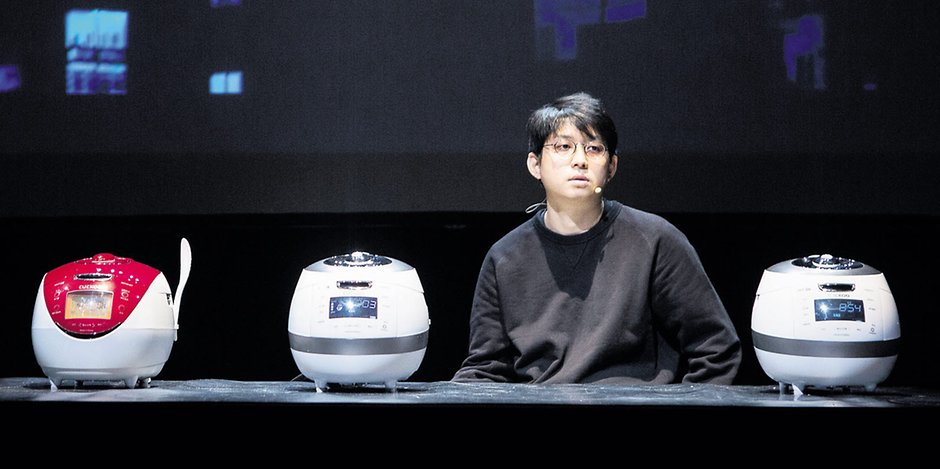

So we see an ad for the Cuckoos on screen, as part of the luscious and lavish video work that is integral to this show, but there are also three Cuckoos on stage, sat seductively on a table, behind which stands the lone and lonely figure of Jaha Koo. The onstage Cuckoos have been ‘prepared’ (in the John Cage sense of the word) – Jaha Koo is not only a writer and performer, he’s a contemporary electronic music composer and producer, working under the name GuJAHA, and he has turned the rice cookers into ‘telerobotic’ objects that manifest as singing, talking, swearing divas. But, as we find out further into the show, they do also still cook rice – or at least, one of them still does. For others, such a mundane reason for existing as making rice is far, far below them.

The Cuckoos are here as foils to Jaha Koo’s monologues, punctuated by very cleverly edited filmed footage, exploring his angst as a thirty-something South Korean, growing up in a country crippled by a financial crisis that, in 1997, resulted in National Humiliation Day, in which the country’s leaders accepted a 55-billion dollar bailout from the International Monetary Fund, on the condition that they implement the organisation’s extensive and damaging changes to fiscal policy that led to a widening gap between rich and poor, endless riots, and a level of national anxiety that permeated every area of life.

Twenty years on, Jaha Koo appraises the effect the past two decades have had on himself and his peers. On screen, and in Jaha Koo’s words (spoken in Korean, with projected text captions in English an integral part of the visual design of the piece) we experience a deluge of challenging ideas and images: two that particularly haunt me are the statement (and accompanying harrowing image) that the artist as a child was cared for by a grandmother who put a clear plastic bag over his head when they went out to protect him from the tear gas; and that when South Korea co-hosted the Olympic Games, the colourful street parades and processions of dancers were the first time he had seen large groups of people on the streets who weren’t demonstrating, rioting or being beaten up by the police.

The piece is beautifully constructed, with different sections each adding another layer to our understanding of recent history and contemporary life in South Korea. I’m not the only person in the audience, I know, who was shocked by the revelations about the part of Korean peninsula that we’d always seen as the saner and more civilised. In particular, the multi-faceted reflections on suicide, which has reached epidemic proportions amongst young people living in the pressure-cooker that is modern Korean life. The generalised observations – on, say, the anti-suicide glass screens separating platform and track on the subway – give way to a very specific story about a dear friend who throws himself from a balcony: ‘When he died, I made this music,’ Koo says, then lets us just listen to the music. It’s a terribly sad but beautiful moment.

Jaha Koo, who now lives between Belgium and the Netherlands, has created a work that captures his native culture astutely – the work is intrinsically Korean – but which also has a modern European style and sensitivity, and sits very well into the body of Flemish new theatre work that explores the possibilities of the performance-lecture. A week later, I’m still haunted by the show’s sounds and images. Food for thought indeed.