Dorothy Max Prior goes to London International Mime Festival 2020 – and finds a fabulous feast of the best physical and visual theatre and performance from across the world

An intergenerational circus-theatre show about family relationships; a multi-media exploration of a fantasy love-affair with a kangaroo man; a show in which a musician and a puppeteer dance with death; a pair of clowns trapped in a cardboard world; and a darkly disturbing dance-theatre exploration of childhood.

London International Mime Festival is always an eclectic mix, and the 2020 edition (the 44th – LIMF is the longest running theatre festival in London) proved to be a fabulous feast of physical and visual theatre. Of the eighteen shows presented – ten from overseas companies and eight from the UK, all of them world, UK or London premieres – I managed to see eight. Another two I’d previously seen and reviewed at the Edinburgh Fringe 2019. So I have ten notches on my LIMF 2020 belt…

The two previously seen shows are This Time by UK company Ockham’s Razor, co-commissioned by LIMF and presented at Shoreditch Town Hall, a new venue for the Festival; and Raven by German company Still Hungry, presented in association with Jacksons Lane. Both use circus to explore the dynamics of the parent-child relationship: This Time has a four-strong cast ranging in age from 13 to 60, and mixes spoken word and floor and aerial circus to explore memory and intergenerational relationship: ‘’The spoken stories might be mostly of struggle, but the physical stories – enacted on a thrilling range of unusual and specially designed swinging and shape-shifting aerial equipment – is of love and support, counterbalancing the concerns expressed verbally.’ Raven is focused more tightly on the mother-child relationship, as three feisty feminist circus artists combine talents to explore personal identity and motherhood: ‘At the start of the piece, each woman, sporting a vest emblazoned with her name, introduces herself – physically, through her own chosen circus skill; then we hear her words, delivered in recorded voice-over, which she listens to attentively, looking out to the audience…Through meeting them via their physical skill, then watching them listening to their own stories, we get a real sense of each woman’s uniqueness.’ I passed on seeing these shows again due to time constrictions – but would happily go back.

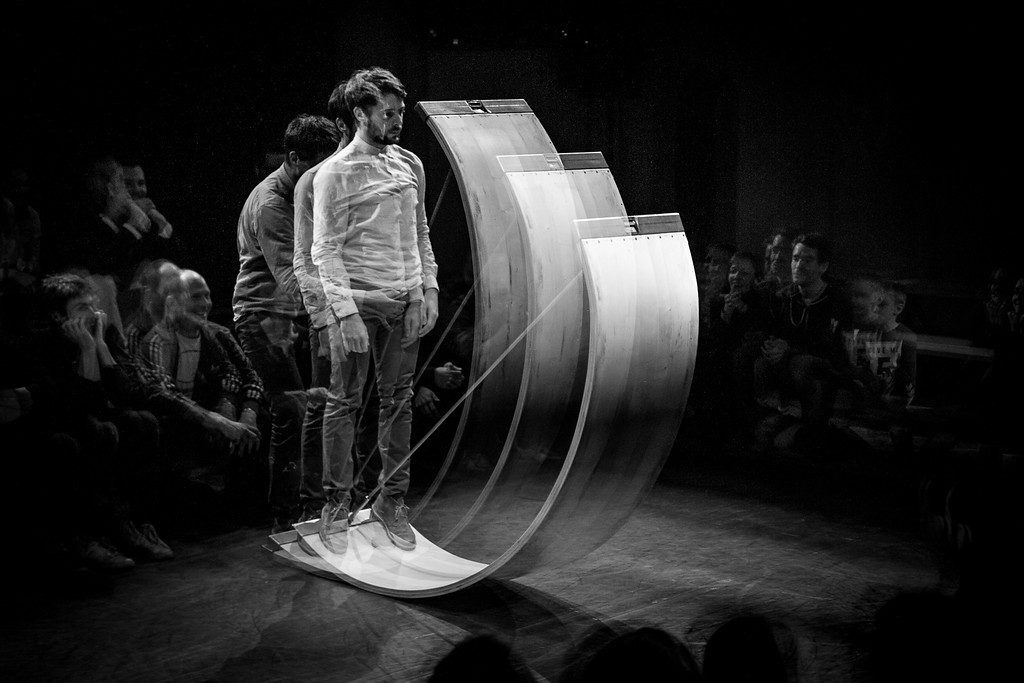

Compagnie HMG: 3D

Also part of the circus line-up was Compagnie HMG, from France, with 3D. It’s an extraordinary piece of work, conceived and performed by acrobat and wire-walker Jonathan Guichard, in collaboration with sound designer Mikael Le Guillou. The centrepiece of the show is a piece of equipment that is a wooden rocking boat (or half-wheel) strung with a wire that can be both plucked and walked along. The special wooden stage is mic’d up, so the show becomes a thrilling meeting of live made-and-mixed music and astounding physical performance as Guichard balances, tumbles, dances and plays with and around the ‘boat’. But that’s only half the story – one of the strongest aspects of the piece is the perfectly pitched interaction with the audience, who are wordlessly guided to co-create the soundscape – be it through call-and-response, mimetics, or sheer braving it out until a response is forthcoming. But everything, always, is done with kindness and cleverness. In the post-show discussion, Guichard said he had three intentions with this show: to explore how you can inventively make music (of different tones and timbres) from movement; to create an interactive piece using audience participation that ‘didn’t take people hostage’; and to work with an unusual piece of circus equipment, to see what that physical material could offer. And 3D certainly does all three magnificently – it is certainly one of the most inventive circus shows you are likely to see.

Fleur Elise Noble: ROOMAN

Puppetry and object animation featured heavily in this year’s programme (see TT’s preview article) – with shows presented including the genuinely cross-artform and experimental piece ROOMAN, seen at Barbican Pit, a visually and aurally sumptuous multi-media exploration of fantasy and addiction, in which the invisible performer-puppeteers move large paper ‘screens’ of all shapes around the stage, these mapped upon with gorgeously executed drawings, animations, and projected images of shadow theatre dancers, as we observe our office worker heroine on her daily trudge through the city to work and home again, to then follow her into what slowly becomes her real life – her inner world whilst asleep. The half-man half-beast ROOMAN character, object of the protagonist’s desire, springs from artist Fleur Elise Noble’s dreams, but also from our collective unconscious, with associations of other hybrid symbols of eroticism, from Greek satyrs and centaurs to Shakespeare’s Bottom in Midsummer Night’s Dream. In a very different mode, the long-string marionetting in String Theatre’s The Water Babies – presented on the fabulous purpose-built Puppet Theatre Barge – proved that beautifully realised traditional puppetry forms still play an important role in LIMF. The outrageously funny Coulrophobia, presented at Jacksons Lane by Opposable Thumb – a new company formed by Dik Downey (previously of Pickled Image) and Adam Blake, also has the traditional skills of puppetry and clowning at its heart – managing to both uphold and usurp the traditions simultaneously.

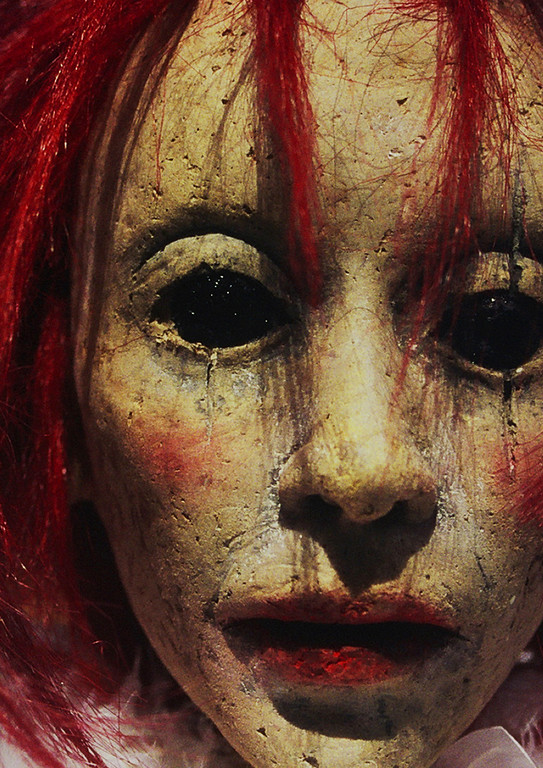

Opposable Thumb: Coulrophobia

Coulrophobia directed by John Nicholson of Peepolykus fame, has been doing the rounds worldwide for a number of years under the auspices of Pickled Image, but comes to LIMF as a fully-formed London premiere for the new company. Its slow-burn development and fine-tuning over the years has paid off, as it’s a truly fabulous showcase of clowning and puppetry skills. The relationship between the two clowns is played out exquisitely, with the traditional ‘master and servant’ status toyed with expertly; comic timing is immaculate; and the constant breaking of the fourth wall to invade the audience’s space done with breathless bravado and skill. The ‘trapped in a cardboard world’ scenario gives ample opportunity for play, as cardboard boxes turn into lifts or showers or tanks. It also provides a suitably surreal setting for what is often a loving nod in the direction of Waiting for Godot: here, the Godot-like Deus Ex Machina character Poco is at first a disembodied voice, but then arrives onstage as a grotesque puppet-clown who would truly justify the ‘abnormal fear of clowns’ that the show title references. The central clown characters are each a fabulous creation in their own right, honed to a T, anarchic, outrageous, and vulnerable in equal measure – but together, the two are invincible. Oh, and the ending is perfect – they do escape Poco’s tyranny, but I won’t say how…

La Pendue: Tria Fata

More puppetry – also with more than a little of the grotesque – in La Pendue’s Tria Fata (again at Jacksons Lane). A musician holds the space with a beautiful mix of pared-down drum kit, clarinet, and accordion. A female performer-puppeteer moves and manipulates, speaks and sings, dons wigs and deconstructs the art of puppetry – all in the service of a story that loosely references the myth of the Three Fates (who decide when our life thread has run out), mixing and mulching this with Mexican Day of the Dead iconography, as we witness an old woman close to death reliving her life and striking bargains with Madame Death to gain a little more time. It is often said that puppetry is the perfect medium for dealing with difficult subjects, and that is demonstrated here. In one gasp-worthy moment, the little old lady puppet, sat in a wheelchair as she reminisces about her life, offers her leg up as an interim payment to Death. The skull-masked puppeteer greedily pulls the wooden leg off… Tria Fata is full of similarly exquisite moments: sublime and subversive glove puppetry in a fight to the death, drum solos and love poems from the fabulous one-man band, beautiful and inventive lighting, a lovely shadow puppetry section, even a flying puppet – and one of the best uses of slide projection I’ve seen in a long while, as we see frozen moments from the dying woman’s life flashing up, overlaying each other, and passing by. The show is delivered in French with English surtitles – and my only criticism is that these titles are hard to read, and probably unnecessary, as the physical, visual and musical elements of the show are enough to carry the story. Life, death and everything in between – this show is a real joy.

Nick Lehane: Chimpanzee

Nick Lehane’s Chimpanzee brings us a very different sort of puppetry. The heartbreaking story of a chimpanzee reared within a human family, then removed to captivity in a research lab, is written and directed by Lehane and enacted with enormous skill and sensitivity by a three-person team of puppeteers using Bunraku-like rod puppet techniques with a beautiful carved-wood puppet. This is a show that is very much what it says on the can – exploring the contrast between the chimp’s current reality in the lab and her memories of a former freedom living life as a member of a human family. There are no enormous surprises in the story – but everything presented is beautifully executed in the service of this story. A dramaturgy of sound and light drives the piece, sharply contrasting ‘then’ and ‘now’. When we are in the lab, the lighting is a harsh fluorescent strip above the animal’s (invisible) cage, and the clever sound design gives us a disturbing bombardment of noises – clattering metal cages, staccato footsteps moving all around the space, and shrill voices and cries. When we are in moments of revery and remembrance, the lighting takes on a soft amber glow, and the soundscape brings us the sounds of a loving home life, playtimes, and outings to meadows and woodlands. We witness the young chimp playing with boxes of pop-up toys and floaty scarves; see her luxuriating in a bath, with loving hands gently pouring water over her; and share her success in learning sign language. The relationship between puppeteers and puppet is beautifully fluid. Sometimes, all three manipulate in classic Bunraku style (with full focus on the puppet). At other times, two will manipulate whilst a third becomes ‘mother’ or ‘father’ or ‘scientist’ or ‘cage wall’. The piece seems to end – but then doesn’t. In the moment, I feel unsure about the ending. On reflection, I see why we need the final picture. It is probably not giving too much away to say that when enduring life imprisonment on what is essentially Death Row, ‘escape’ can take many forms. A disturbing but beautifully realised piece of work.

Peeping Tom: Child

Also disturbing – although this time through a bombardment of surreal imagery dragged up from both the collective unconscious and the content of 24-hour news channels and social media posts – is Peeping Tom’s Child (Kind), the final part of a family trilogy (families seem to be something of a motif in this year’s LIMF). Like its predecessors, Father and Mother, Child is dark and disturbing, and features fantastic physical performances and a stunning scenography. But for me, Child was a step too far – a really uncomfortable roller-coaster ride. A grown woman – the marvellously named mezzo-soprano Eurudike de Beul – plays a parentless girl child, abandoned in a mythical forest, replete with psychotic hunters and surreal stiletto-heeled fauns. The child is a simpering parody of girlhood – knee-knocking, tugging on her pink party dress, showing off her big white knickers – as she rides her little bicycle round and round in the forest, and (with a nod to numerous fairy tales and to Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories) befriends and interacts with the ‘magic helper’ creatures she encounters therein. The forest is bordered by crumbling cliffs tended to by white-coated forensic scientists/archeologists. The cliffs are very obviously made of lightweight polystyrene, making a mockery of the heavy lifting and avalanching tumbles (deliberate, we assume – perhaps to remind us that this is all unreal). A couple of hikers appear, pursued by the hunter who kills the female, shooting her repeatedly (cue an immensely clever choreographic section as the body twitches and leaps from the ground with each shot). He then trains the little girl to use the gun. And so it goes. I’m afraid I also twitched uncomfortably in my seat for a very long 85 minutes. On reflection, I can appreciate the archetypes referenced, the challenge to our, on the one hand, idealising childhood in general and the innocence of little girls in particular; and, on the other hand, sexualising girls and bombarding children with our mess and distresses. I get it. But I didn’t feel happy – particularly as a real child is there onstage in the mix, exposed to these horrible images. I just wanted it to go away, and was relieved when it ended… Key question: are you part of the problem or part of the solution? In Child, Peeping Tom stay fixated on the problems without offering any solutions. It’s a common stance in our contemporary society. Personally, I need to witness some inkling of hope or redemption, not just the relentless, satirical flagging up of all that is wicked in the world.

Told By An Idiot: The Strange Tale of Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel

Also showcasing magnificent physical skills – this time in the honourable tradition of mime, clown, vaudeville and slapstick – came Told By An Idiot with The Strange Tale of Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel. In the programme notes, director Paul Hunter’s expresses a fascination with ‘the deconstruction of an iconic figure and the idea of creating a true fantasy’. Here, he imagines a relationship between Chaplin and Laurel that almost certainly didn’t exist; a ‘comically unreliable’ tribute to these two greats of physical comedy. It could be said that in the retelling of known facts, the re-imagining of the relationship, and the speculation on events that might (in a parallel universe) have occurred, Hunter is inventing the truth.

It is such a beautifully realised show. The relationship between live music (mostly piano and sometimes drums or clarinet) and physical action is magnificent – a thumped bass pedal and a mimed knock on the door perfectly synchronised; a drum solo tumble down the stairs. The live piano playing emerges from a recorded ragtime soundtrack; the pianist emerging from the ensemble, as figures leap on board a ship about to depart from the UK to America. Charlie and Stan turn out to be cabin mates, supposedly the start of their relationship. A repeated motif of ‘Smile though your heart is breaking’ becomes the theme of the show. We have flashbacks to Charlie’s birth in an impoverished Victorian London, and his drunken father singing ‘I beg your pardon, you’ll find me in the garden’; flashes forward to years later when Stan calls on Charlie in his Hollywood mansion only to be sidelined by the butler, leaving him mournfully clutching the portrait that was to be a present.

The multi-tasking ensemble are fabulous – bringing a a mix of ages and experiences to the show. Heavyweight Nick Haverson is a wonderful actor with a great vaudevillian sensibility. Amongst other roles, he plays impresario Fred Karno, Charlie’s dad, and – in a wonderful moment of theatrical transformation, stuffing a pillow down his shirt in full view of the audience – Ollie Hardy. Amalia Vitale (in true Music Hall style, channelling Vesta Tilley and other legendary cross-dressers) plays Chaplin with an immense amount of brio. Younger actor Jerone Marsh-Reid captures Laurel’s lanky gawkiness perfectly, and is also put to work as various small roles (bell boy, doctor etc.) Sara Alexander, like all the others, is rarely off-stage. Her principal role is as pianist – and she tickles the ivories beautifully – but she also doubles up as Chaplin’s mother in a fabulously funny birth scene.

It was so wonderful to see this show in Wilton’s Music Hall, which has been beautifully and lovingly preserved, with multi-levelled stage, gallery, and gorgeous spiralled-wood posts. The use of the auditorium (and audience) in the piece is so good: jaunty entrances and exits through doors; nods to the venue’s origins in a grand sing-a-long with Charlie’s dad; and a fabulous scene where the pianist abandons her post and demands that someone from the audience steps in to play piano (we got Fur Elise on this occasion – apparently it can be anything from a Rachmaninov concerto to Chopsticks, but there is always a volunteer.)

It was great to see that in a London International Mime Festival programme that embraced so much experimentation and playing with form, one of the most successful shows is right back to the roots, with a wonderful demonstration of the power of mime, clown and devised physical theatre.

Featured image (top): Told By An Idiot, The Strange Tale of Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel. Photo by Hugo Glendinning

London International Mime Festival 2020 ran 8 January to 2 February 2020 at various venues across London. See mimelondon.com

La Pendue: Tria Fata