Dorothy Max Prior discovers a world of age-old archetypes and new mythologies in a diverse selection of work seen at the London International Mime Festival 2018

If there’s one defining characteristic of work presented at the London International Mime Festival, it is that the work is hard to define; slipping and sliding as it does between artforms and modus operandi. But diverse though the work that makes up its component parts might be, a curated festival inevitably takes on a personality of its own. Two strands that struck me when viewing, and musing on, the body of work presented in this year’s Festival is that it felt particularly strong in women theatre-makers; and that there were many shows that seemed, in various and diverse ways, to be investigating the lure of the mythological and archetypal.

Peeping Tom’s Mother (Moeder) ticks both boxes. The lead creative force on this show is director-choreographer Gabriela Carrizo, working alongside assistant director and dramaturg Franck Chartier (the two are joint co-directors of Peeping Tom). And Gabriela Carrizo is completely upfront about her desire to explore the Mother archetype, saying: ‘[The show] is not about one mother, but about several mothers. We talk about motherhood, and the absence of it [searching] the subconscious to reveal what the mother carries as desires, fears, suffering or violence.’

Moreover, this show gives us a fragmented, dreamlike narrative that explores attitudes not only to motherhood, but also to family dynamics, history and heritage. We meet, amongst many other characters, a matriarch at her funeral, a woman giving birth, a curator, a cleaner, a living museum exhibit, a patriarch who has outlived both of his wives, and a couple whose baby never made it out of the incubator – grotesquely, growing to adulthood in this contained environment. Amber Vandenhoeck’s set is a marvellous thing to behold, morphing as it does from museum/art gallery to labour room to recording studio to funeral parlour. These changes are enacted by switching our point of view from one part of the stage to another, or by changing our perception of the space, using light and sound. As, for example, when we see a glass-sided booth at the rear of the stage lit in the cold blue light of a hospital, suddenly (with the birth of the baby) morphing into a red-lit recording studio, the mother now a diva howling ‘Oh baby, baby…’ into a mic. Sound is often used as a dramaturgical driver of the piece. There is a quite extraordinary scene exploring the archetypal feminine element, water, in which not a drop is seen but we hear the constant splashing and slurping of water filling the stage, the performer responding to this with an exquisite choreography of twists and turns and backward falls, flailing around in an imaginary pool like Alice in Wonderland. Elsewhere, family portraits come to life, revealing bloody guts within, and a coffee machine takes on a persona of its own, a motherly figure dispensing solace in the form of espresso – or is that expresso? – to all the family. It is a magnificently slick and clever show, with tremendous performances given by actor-dancers with exceptional physical skills: Mother is an enormously intelligent work, its images deep and resonant, coming back to haunt you long after the show. I felt something of a lack of emotional engagement, but there was so much to occupy my mind that this didn’t bother me too much.

From the Mother to the Bride (the female manifestation of Jungian archetype The Lover). Gabriela Muñoz’ Perhaps Perhaps Quizas is a very different kettle of fish: where Mother is epic, distanced, cinematic, cool, exploring and presenting us with a million and one ideas and images, Perhaps Perhaps Quizas (featuring Gabriela Muñoz, aka Chula the Clown) gives us the perfect example of the intimate, one-woman, ‘one idea beautifully executed’ show. As we arrive in the auditorium, we see a simple set depicting an old-fashioned drawing room, with a little table sporting a lacy cloth and cake-stand, a chintzy sofa, and a coat-stand. We see a woman onstage, behind a net veil which is draped from the ceiling. She’s in a bridal dress, and sits quietly writing letters, like a Victorian heroine. She comes out, and it becomes clear that she is preparing for her wedding day. But where is the groom? He is there, but he needs to be discovered. After some playful exploration of the men on offer in the audience, one is picked, and invited on stage. He is flirted with, and put through a wedding ceremony (priest and bridesmaid also picked from the audience); and then comes the cake, and the champagne, and the wedding dance, and first kiss…

It is an enormous risk, to share your stage with an audience member as your leading man for almost your whole show. But Gabriela Muñoz knows what she’s doing. The encounters with the ‘groom’, and indeed with all of her chosen accomplices, demonstrate her exquisite sense of timing, and her feeling for how far you can push someone in the moment. We never feel worried for the audience members on stage – they are handled with care and love in every moment, even when (especially when) they are being teased. The play with objects is also superb: the way the strawberry on top of the cake is thrown away with a wrinkle of the nose; the gentle handling and fondling of the man’s jacket on the coat stand; the champagne ‘accidentally’ poured down her front; the endless rolls of toilet paper unwound to become aisle or priestly dog-collar or bridesmaid’s fascinator gone awry.

Like all good clown shows, the laugh-out-loud humour is balanced with pathos – moments of ludicrous bathos taking us from one to the other. The archetypal event that is the wedding offers a lot for a clown to play with, and expectation, desire and disappointment are all portrayed cleverly. The Lover is the archetype of play and sensual pleasure: living in the moment and tuned into her physical environment. Gabi Muñoz captures her perfectly.

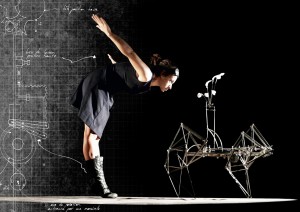

Compagnie L’Insolite Mecanique’s promenade show Lift Off is a beautiful exploration of the Child archetype, and particularly the Innocent or Magical Child, whose qualities are an optimistic desire for freedom. ‘Let’s open my cage and see what happens!’ says creator and performer Magali Rousseau. The show is a heartwarming exploration of playfulness and the world of the child, enacted by Magali Rousseau, a musician on laptop and clarinet, and a roomful of little machines operated by cranks and pulleys, designed and made by Rousseau herself.

The audience processes through a room filled with these extraordinary automata whilst the performers animate each structure in turn; ambient music, poetic text, and simple, stylised physical action lending weight to the images and bringing us stories of family life and heritage. We learn about the girl’s mother, grandmother, grandfather, and a great many great-greats in this family of fishermen and farmers. The room plan of a house is drawn with chalk on a revolving turntable, as Magali Rousseaux says: ‘Always leave the house with a clean sink, little girl – a clean sink and clean knickers…’ As the girl-child learns to spread her wings and fly – a recurring image throughout the piece, expressed in the performer’s body, and with beautifully-crafted metal figures zipping along wires – she wonders: ’What happens to the air I’m stirring with my wings? ’and ‘If I fall, will you catch me?’ In the yard are chickens with clipped wings – represented by a whirring and spinning contraption in which little feathers flutter up and down without ever going anywhere. The element of air, the lyrical element of the child, balances with the motherly element of water: one of the more complex of these beautiful machines gives us a revolving metal ball heating water to produce a hiss of steam; and another features a goldfish in a glass bulb orbiting slowly around within a solar system. Listen closely and you can hear the song of the mermaids… A truly beautiful show that left me humming with delight.

If there is an archetype that we might align to Yasmine Hugonnet’s Le Recital des Postures, it would probably be the Empress, who represents the physical body and material world; worldly power and earthly pleasure. Hugonnet presents us first with a clothed body, then with a naked body, which is placed sculpturally in the space (a bare white stage, the only adornment being in the excellent lighting design by Dominique Dardant). The gaze is all: she is there to be seen, we are there to see – but what are we seeing? Hugonnet says in her programme note: ‘it is a symbolic body, archetypal, social, as well as a place of communication.’ As the piece progresses, we become ever-aware of the archetypal images of the sexually mature female body. Here, a Geisha pose; there, an image from an Egyptian frieze or a Grecian urn. Hugonnet is a very able performer (in every sense of that word) and the poses she creates through almost imperceptible movement from one state to another are indeed visually beautiful and evocative. Her control of her body’s movement is exceptional, although for much of the hour, delivered in silence with just the squeaks or thuds of her flesh on the floor’s surface as accompaniment, I feel that I am watching an exercise in the physical capabilities of the artists’s body, rather than a show. In the final section, in which Hugonnet allows her voice to enter the space, the hair that she has been teasing and playing with as a sculptural object throughout the piece is pulled up into a kind of beehive formed around a plastic drinks bottle. With the arrival of the voice, and with a hint of humour and idiosyncratic humanity, I become far more interested in the body on stage. Suddenly the object of our gaze seems to be addressing her own part in all this in a way that I felt was previously lacking. Yes, there are beautiful evocations of a whole history of representation of the naked female form in art, culture and mythology; and I am aware that a woman presenting her naked body (whether onstage or in a gallery) is different to a man presenting a woman’s naked body, and that everyone should be free to perform in whatever state of dress or undress they wish to – yet I find myself musing that in this day and age, placing a young, fit, naked female body in a space and inviting the audience’s gaze just doesn’t feel enough. I want some sort of challenge or commentary from the artist, and this only begins to emerge in the last five minutes. I think comparatively of the work of La Ribot, and feel that Hugonnet has a lot yet to learn, beautiful though her Recital des Postures might be.

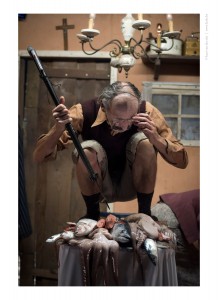

300 el x 50 el x 30 el is an epic production, both in its subject matter and its execution. It takes as its starting point one of the most archetypal stories of all, a version of the Noah’s Ark myth of natural disaster and salvation, and it explores this through a delightful interplay of live action and live-feed video enacted on an ambitious film-set-on-stage, comprising a village made up of six wooden shacks, a forest, a clearing, and a pond. In the clearing, by the pond, sits an angler, biding his time, seemingly at peace. In each wooden shack, a different surreal scene unfolds, as people play a waiting game, knowing that a disaster is imminent; that only some will be saved; and that nobody quite knows exactly when this will occur. Meanwhile, three men with a camera on a dolly track work their way around the village, filming the shacks through the open fourth walls, so that we get to see what’s happening inside. Or do we? There is of course the possibility that some scenes might be pre-filmed – we assume not, but how are we to know? The fact that we only see the inside of the shacks onscreen, never in the flesh (so to speak) offers us the opportunity to reflect on the ‘real’ versus the mediated image: just when and why do we believe the evidence of our own eyes? Is it true that the camera never lies? What we see is the stuff of dreams – or nightmares, more like. Images dredged from the collective unconscious Jung’s primordial soup of innate archetypes, which turn up in religions and mythologies worldwide, pass by in quick succession, framed by the ever-faster moving camera lens. Sacrificed beasts, people who grow bird heads or morph into fish, people who watch other people gorging while they go hungry. With each camera circuit round the space, the scenes become more bizarre and darkly humorous: a darts match turns into a William Tell act gone wrong, a wild-eyed boy blows up toy villages with fireworks, and a limp-dicked masturbator watches his wife give birth to a conch shell. There’s an Hallelujah moment as a dead sheep is dredged up from the pond, and the energy of the piece shifts, with a sense of waiting growing more intense, occasional forays outdoors by the villagers, who gather to gaze dumbly at the sheep swinging above them. Our focus now moves to a young couple who venture out into the woods to consummate their love, with a sense of living for the moment, as time might be about to run out. A grand finale sees all of the cast of fifteen actors joined by a horde of extras in a glorious shamanic shake-out to Nina Simone’s Oh Sinnerman. There is nowhere to run to, nowhere to hide – let’s surrender and await our fate joyfully…

The show is rough at the edges, a little raw and wild, which only adds to its appeal. It is great to learn afterwards that this highly ambitious piece of work was created a few years ago by a group of young artists, theatre-makers and film-makers with very little resources. FC Bergman, as they are collectively known, literally made it themselves – building the shacks, gathering together the excessive amount of props, roping in actor friends. They had no idea then that their one-off creation – envisioned more like the making of an independent arthouse film or a site-specific show rather than a regular touring theatre piece – would still be on the road many years later, now supported by Toneelhuis in Antwerp, where the company are resident artists.

There is a lesson here: don’t shy away from making work of scale, step beyond perceived limitations and see what happens. To evoke the archetypes one last time: be a Dreamer; be a Hero.

Featured image (top): Toneelhus/ FC Bergman: 300el x50el x 30el

Peeping Tom: Mother (Moeder) was seen at Barbican Theatre, 24–27 January 2018

Gabriel Muñoz: Perhaps, Perhaps, Quizas at Jacksons Lane, 19–21 January 2018

Compagnie L’Insolite Mecanique: Lift Off at Barbican Pit, 23–27 January 2018

Yasmine Hugonnet: Le Recital des Postures at Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells, 19–20 January 2018

Toneelhuis/ FC Bergman: 300 el x 50 el x 30 el at Barbican Theatre, 31 January–3 February 2018

All shows were presented as part of the London International Mime Festival which ran at various venues from 10 January to 3 February 2018. www.mimelondon.com