‘At the beginning we didn’t have a map, or even a destination’ say Ockham’s Razor in the programme notes for their latest full-length show Not Until We Are Lost, which opened the London International Mime Festival 2013 at the brand spanking new Platform Theatre in King’s Cross (a cavernous building that is home to the newly enlarged Central Saint Martins art school).

‘It’s terrifying to be lost; to not know whether to keep moving forward, or try and find your way back, or whether you should stop’, they say. Yet in the getting lost, straying from the usual path into new territories, we discover things we might never have otherwise discovered – new ideas, new experiences, new aspects of ourselves. In life, as in theatre-making, ’tis better to have run the risk and really lived, rather than to have just taken the path you know best which offers the least challenges and risks. It is for all these reasons and more that Ockham’s Razor cite the Thoreau quote ‘not until we are lost do we begin to find ourselves’ as the inspiration for their new show.

The company – Alex Harvey, Tina Koch, and Charlotte Mooney – have, for quite a while, wanted to make a show ‘with the audience on stage alongside us’. In March 2012, before the process of making this new show got properly underway, I met the trio at artsdepot in North London, where they were working with Oily Cart on Something in the Air, a show for young people with severe physical and/or learning disabilities. In this tender and lovely show evoking the turn of the year and the flavour of the seasons, the children are placed in swinging cradles while the Ockhams aerialists unfurl from brightly-coloured silk ‘nests’ to swing gently around with the children, bounce balls and flutter leaves above, between or under them, and perform gentle trapeze or corde lisse routines so close that the children could almost reach out and touch them. Alex and Tina tell me that they loved working in this way for the Oily Cart collaboration, and the company were keen to explore the possibilities of a similar intimate relationship with the audience in their own new show. At that time, they had just started working with composer Graham Fitkin, and were excited by the idea of exploring the concept of a mobile choir interweaving with the audience (an idea also explored recently by H2Dance whose show Something to Say, also a promenade work featuring a mobile choir, played at Summerhall at the Edinburgh Fringe – there must be something in the air, so to speak). In the Ockhams case, the desire to work so closely (literally) with singers came out of their experience working as performers on Improbable’s version of the Philip Glass opera Satyagraha for the ENO. Alex says he ‘loved the power of being that close to the singers – the physical effect’. For the early dates of Not Until We Are Lost the company have worked with local choirs in regions they’ve toured the show to, but the LIMF run features a choir specially put together for the show.

A residency at the Generating Company’s space in France, then a block of time back at artsdepot (where they were circus artists-in-residence 2011-2012) culminated in the first showing of the work there in September 2012. Something in the Air is also supported by Dance City in Newcastle, and by the Lancaster collective Live at LICA, who specifically supported the development of Graham Fitkin’s specially composed score. Also name-checked for their support are Circomedia, the Bristol school for circus and physical theatre where the Ockham’s Razor trio trained and met. Circomedia co-founder Bim Mason is on board for the show, credited with ‘additional direction’, as is Matilda Leyser, the renowned aerialist who taught the company and whom Alex cites (with Bim) as one of his main influences.

Talking of influences and early training: it is interesting to note that the company members have backgrounds in visual art, scenography and literature that prefigure their circus training – so hardly surprising to note that their productions have an intelligent and multi-textured sensibility offering a view of ‘circus’ as a place for metaphysical reflection on the nature of human existence. The visual aesthetic is such that entering the space at The Platform there is the feel of having walked into an all-enveloping sculpture.

It’s always interesting to meet artists thick in the process of making work and hearing what the intentions might be – then to compare and contrast those impressions with what you witness when you finally see the show. I’m impressed by the great metal structures above my head, glinting in the ghostly, deep-sea green light – but my eyes are most strongly drawn to two ‘stations’ on either side of the room: one features an impressive pair of harps; the other a kind of see-through tower flanked by a Chinese pole. I recognise, if that’s the word for something you’ve pulled up from an image in your imagination, Alex’s description all those months ago of creating a ‘Perspex chimney’ with which to play with the notion of ‘rock climbing in reverse’. He said then that he wanted a scene in which all the performers get wedged into the ‘chimney’ together, and that he wanted the audience close up, peering in – and indeed, that’s what we get, although not till the end of the show. My favourite scene using this particular structure is a duet on, in and around the ‘chimney’, a play on quest and struggle and the offering of a helping hand to a fellow human being. And it’s very lovely that it’s a ‘she’ who offers the hand of support from above to the ‘he’ floundering below.

When I met with the company, they had commented on the fact that the equipment often leads the way in the devising process – and that this was particularly the case in the creation of short pieces Memento Mori (a haunting and tender trapeze double by Alex and Charlotte that made them Jeunes Talents Cirque laureates in 2004) and the gorgeously forlorn Arc (which premiered at the London International Mime Festival 2007), performed by the trio of Ockhams on a less conventional piece of circus equipment – a specially constructed tipping and rocking ‘raft’ made of metal bars. These two pieces, with a more lyrical third called Every Action…, formed a very successful triptych that subsequently toured extensively across the UK and really established Ockham’s Razor on the contemporary circus map. A first full-length show, The Mill, premiered at LIMF 2010.

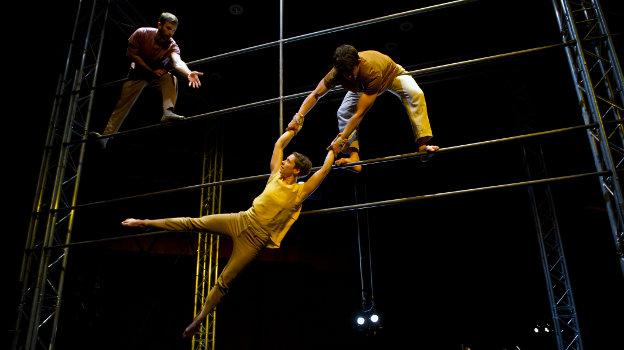

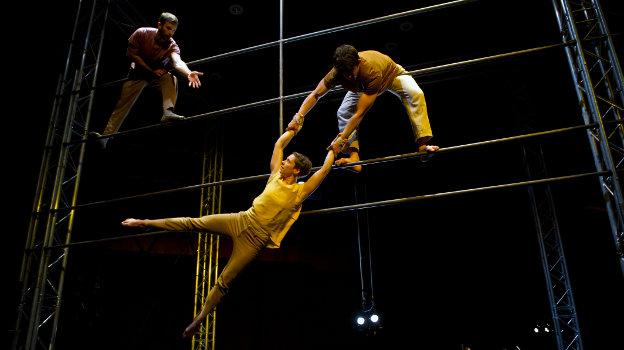

In the case of Not Until We Are Lost, the equipment offering devising possibilities included not just that Perspex tower but also an enormous reworking of the metal rack cum raft idea used in Arc, here mutated into a great swinging thing that occupied the space in many different ways using various planes and levels. At first it makes a kind of triangular configuration with the floor, the five aerialists clambering up like monkeys, or human babies, only to slide down again, or dangle by the arms until ‘rescued’ by their mates. Again, I remember Alex’s voice all those months earlier talking about wanting to work with a kind of human snakes-and-ladders idea. One step forward, two steps back – two steps forward, one step back… the human condition in a nutshell.

At another point in the show, the frame becomes a great big playground swing, the five performers chasing it with childlike glee, playing the game of daring to jump, or chickening out at the last moment. When all five are sitting side by side, it has the feel of a Busby Berkeley moment of unified swinging. Then again, turned upright the frame provides the site and wherewithal for a whimsical threesome (two boys and a girl) to act out signs of flirtation and friendship, acceptance and rejection.

Despite the impressiveness of all the bits of kit, some of my favourite moments of the piece are the small ones: a solo performer way above our heads, up in the ceiling of the space, making her way quietly along the metal walkway usually only used by technicians and riggers; a choir member weaving through the crowd, walking past me, singing and smiling to herself; the harpist completely focused on the creation of the music, almost oblivious to the audience; a performer tearing paper into pieces that float to the ground like the paper leaves in Something in the Air. Time and again I find myself thinking that the development from that piece to Not Until We Are Lost is clearly on display: from working with children with severe disabilities, Ockham’s have developed a lyricism and tenderness in their performance that is very special. All the elements of the piece – the robust but understated physical performance, the angelic music, the magical lighting, not to mention the beautifully understated costumes in their soft and sensual palette of taupe and rust and rose-pink (designed by Bicat & Rigby, Tina Bicat being a long-standing collaborator of the company) – come together to create one very aesthetically pleasing whole.

If there are criticisms of the show, they are minor niggles. There’s a device for moving the audience around using a rope which people are encouraged to catch hold of that just doesn’t work well– at least not on the night I’m there. The fact that it is ‘explained’ at the start of the show by one of the company’s producers is something of an alarm bell – audiences shouldn’t need to be told in advance how they’ll get moved round a space. And the inclusion of a large number of woven bamboo portable stools for the audience to sit on means that there is an incredibly annoying squeak and creak going on throughout, marring the mood set up by the gentle singing and harp-playing, not to mention the trip hazard as we move around. Ditch the stools, folks!

For some people, the fact that the show is made up of a series of self-contained vignettes rather than having an obvious through-line is an issue – but not for me. The analogy with shows of this kind that works for me is that it can be viewed like a book of themed short stories or poems that develop and interweave ideas and images, rather than as a novel or traditional ‘play’ – and personally I can see nowt wrong with that. I’d say further that attempts to forge hour-long linear narratives that hammer home a plot often go awry in circus-theatre. Anyway, as Tina Koch puts it, ‘theatre is naturally inherent in circus’. One thing I’ve always enjoyed about the company’s work is the awareness of, and play upon, those moments of intrinsic theatricality – the arm reaching out to help, the girl passed from hand to hand, the momentum of that swing, the clutch for dear life on the bar… I’m also very fond of the way that the equipment is allowed to tell its own stories: in this case, that things aren’t necessarily what they seem, that nothing in life is as rigid as we think it is, and that a change in perspective can change everything we think we know.

With a decision (to-date, anyway) not to use text in their shows, Ockham’s Razor are working hard at proving that stories – meaningful human stories of loss and gain, joy and sadness, solitude and togetherness – can be told using physical, visual and musical forms. A great choice, therefore, for the opening of the latest London International Mime Festival.

Ockham’s Razor are produced by Turtle Key Arts, and are an Arts Council England National Portfolio Organisation.

Not Until We Are Lost was seen by Dorothy Max Prior on 10 January, the opening night of the London International Mime Festival 2013, at The Platform Theatre, King’s Cross, London.

Ockham’s Razor tour Not Until We Are Lost across the UK from February to June 2013. For dates and full details see here