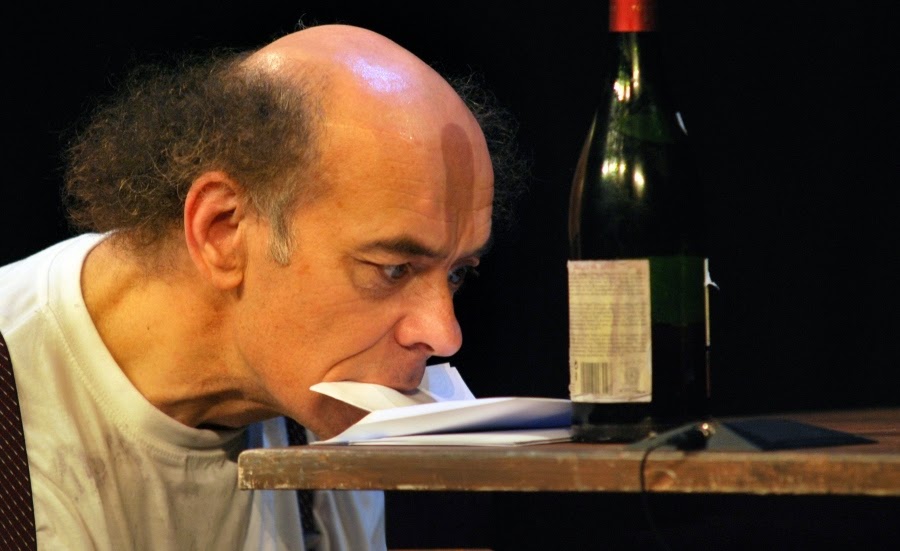

Paulo Nani saunters onto the stage, wearing a minimal costume of black trousers, lace-up boots, a white T-shirt and clip-on braces, with his hair in tufts. He pauses, looks at us and raises a quizzical eyebrow. We laugh and are subtly drawn into his world. He bows and we applaud, which he acknowledges yet undercuts with deprecating looks and gestures. He rapidly speaks a couple of sentences trying out several languages, French, Italian, German, Danish, punctuating each one with bewilderment at our lack of understanding, as though to say, ‘Where am I and who are you?’ Eventually, he seizes upon English, and announces that he’s going to write the same letter in several different ways. Shrugging his shoulders apologetically, he gestures towards a small table on which are a few small props – a pile of envelopes, stamps, a half-full bottle of wine, a glass, a framed photograph, and a red pen. In these few minutes he has set up a tension between the apparent simplicity and naivety of the clown and his precise skills, in which each gesture and look is calculated to respond to and engage with our reactions to him. There is a complicity with the audience which suggests ‘I’m just like you’ – but it is already clear that he is a master clown.

He holds up a storyboard on which is written ‘Normal’. Sitting down at the table, he picks up the pen, takes a swig of wine, evidently horrible, which he spits out, looks at the photo, turns it away from him with regret, which reveals portrait of a woman. He quickly writes the letter, licks the envelope and sticks on the stamp. He stands up, but realises his pen had no ink, so takes the letter out, and throws it away, then exits to our applause. He returns with the storyboard, resets the props and reveals the next style. The resetting becomes a running thread, punctuating the styles, and is playfully woven into the fabric of the performance. Likewise, throughout the performance he creates a soundscape with the props. Banging down the wine bottle, the sound of the wine being poured, tearing up the letter, scraping the chair on the floor, plus his use of grunts and tuts, provide a varied musical and rhythmic accompaniment to his actions, fitting each style.

Some of the styles are performance genres, such as ‘Western’, ‘Horror’, ‘Silent Film’. Others, such as ‘Backwards’ ‘Surprise’, ‘Two Things at the Same Time’, ‘Without Using Arms’, ‘Repetition’, demanding virtuosity in the physical difficulty of accomplishing them, and imaginative play in how to approach them. Each style requires a different performance rhythm and level of play. He uses grotesque mime in ‘Horror’, in which drinking the wine turns him into a monster. In ‘Circus’ he includes many over-the-top bows, and cries of ‘hup’ at each movement. ‘Drunk’ is beautifully nuanced in that Nani performs it as someone who is clearly drunk, but is attempting to appear sober. In ‘Without Arms’ he constantly teeters on the edge of failure. To pour out the wine he has to pick up the wine bottle in his mouth, hold it in his knees, remove the cork with his teeth, manoeuvre the bottle onto the table, tip it to gently dribble the wine into the glass, using the pen in his mouth to guide him. The tension mounts during this sequence, but there is laughter at the absurdity of the task, the contortions he has to go through, and applause when he succeeds. Whilst he uses some time-honoured clown gags throughout, such as a routine where he gets his braces stuck round his chair in ‘Drunk’, his timing of the gags and the skill with which he builds them up, delaying the moment of realisation for him and the audience, are superbly done.

Throughout the performance he playfully engages with his audience with looks and gestures, occasionally asking them to help him by holding props. This culminates in ‘Circus’ in which he chooses a seated audience member to throw the pen directly into his hand. As expected she fails at first, but eventually she achieves this feat to both applause and laughter. He then presents her with a bunch of flowers, but again undercuts this by exiting and returning with a handful of heather to announce that this is the first time anyone has ever succeeded, and this would have been her consolation prize for failure. Yet the finale is itself a beautifully fluid piece of movement in which he reprises the show and all the styles he has performed, before ending with a magic trick in which the photo has disappeared from its frame.

Created in 1992 with Nullo Facchini, Nani has been performing The Letter throughout the world for 27 years and has done over 1500 performances honing and polishing it, so that it has become a classic of clowning. Whilst it might be argued that the show is not pushing performance boundaries, I was nevertheless reminded of Raymond Queneau, the French experimental writer and member of the avant-garde group Oulipo, whose book, Exercises in Style, first published in 1947, consists of a short story about a man catching a bus, who sees a man in a straw hat, and then sees him later at the station. This deliberately banal story is then reworked in 99 other literary styles and is an experiment in form and virtuosity. I don’t know whether Nani has drawn on Queneau’s book for The Letter, but it strikes me that the show is an experiment in virtuosity and creativity too. The constraints of compression, and working on a small canvas, plus the simplicity of the story, paradoxically give Nani the freedom to play across a broad yet detailed range of styles. The show is an absolute delight, and Nani is a consummate performer, who also reminds the audience of great clowns of both the past and the present – of which Nani is undoubtably one.