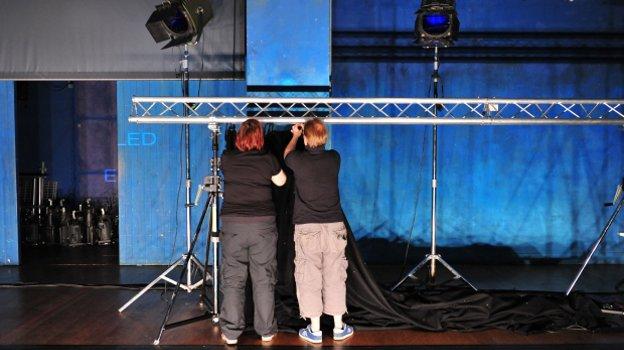

Let’s hear it for the technicians, those anonymous, uncredited foot soldiers of the performing arts who, dressed in black, with bowed heads, put in the cables, the leads, the woofers, the tweeters, the mixing desk, the amp, the mics, the floods, the cans, the spots… Quarantine’s Entitled puts the technicians centrestage, using the usually hidden choreography that creates the performance environment as the subject of the show.

It is, I suspect, a ‘Marmite’ show. Taking the form of a get-in, then a get-out, it invites a love-it or hate-it response. I hated it. I could try to temper this very raw subjective response, but let’s get that response out of the way upfront! As someone who does get-ins and get-outs all the time, I just despaired of what I was witnessing, and failed to understand why anyone would think this would make interesting viewing. Apart from any other criticism, it was pseudo-realistic rather than realistic – and I found that even more irritating than the basic concept. By the time they got round to putting down the dancefloor, I had my head in my hands. When it reached the point where I realised that the get-in was going to be followed immediately by the get-out, I was close to despair.

In situations like this, I start to imagine how I’d feel if I invited someone who was intelligent and open-minded, but unversed in contemporary performance trends, out to see this work. What would it tell them about ‘performance’ as an artform? I think Entitled would confirm many people’s prejudices of ‘performance’ as a forum for self-indulgence. What, I wonder, is the purpose in creating work that that can only be read by people versed in the form? There’s a smug knowingness to it that makes me itchy with irritation.

That said, if you take away all of the above – the physical/visual narrative of the get-in/get-out – there is another, interweaved ‘offstage’ story not about objects but about the people who perform: the musicians and the dancers (and indeed technicians) who have lives beyond the limits of the footlights. I enjoyed some of the (presumably) autobiographical-confessional texts reflecting on the role of the dancer/musician/technician, the balancing of home and work lives, and the dictats of body image, abilities, and ageing. This, I felt, was a far more interesting line of theatrical enquiry than the ‘play’ around the soundcheck and tech run and whatever (which, in any case, I think was explored more successfully, and with more wit and vim, by Forced Entertainment in Bloody Mess).

I should add here that I have enjoyed Quarantine’s work immensely in the past, and indeed that I saw this show on the same day as I went to the Quarantine installation The Soldier’s Song, also presented at Summerhall, which is as beautiful and moving a work as I could have hoped to witness…