This summer, as advertisements in the Tube trumpet, the world will come to London. For some theatregoers, the world will already have arrived, with the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s revival of their late, visionary choreographer Pina Bausch’s Global Cities, ten pieces of ‘dance-theatre’ inspired and commissioned by metropoli ranging from Rome to Hong Kong. The current revival is part of the London 2012 Festival and concludes the Cultural Olympiad. At the Barbican on 9 and 10 June, the 1996 Global Cities instalmentNur Du (Only You), was presented. Nur Du was researched in California, Arizona, and Texas, but according to the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s publicity, is Bausch’s ‘Los Angeles’ project. A thematically clear, technically impressive, whimsical work of art, bursting with Bausch’s trademark overcharged emotion,Nur Du demonstrates that the worlds of dance, theatre, and performance art have lost a treasure by Bausch’s untimely 2009 death. As a portrait of 1990s Los Angeles, however, Nur Du is far less of a triumph.

Admittedly, the neo-Expressionist Bausch has never claimed to hold a mirror up to nature. In Nur Du, the set, designed by frequent Tanztheater Wuppertal collaborator Peter Pabst, consists of an ultra-realistic three-dimensional representation of a stand of giant redwood trees, but the real landscape is that of the human psyche. Early in the piece, a blonde woman in a little black dress walks through the air, carefully, deliberately, always looking ahead, never down. The woman balances not upon a tightrope but the contracted biceps of a queue of men in baggy suits. As she progresses, the men behind her scramble to queue up at the front. Like an icon in a street festival, she is paraded across the stage. Only this woman’s beauty, her devotees suggest, could inspire such idolatry. Only her perseverance could bring her across the wilderness of the West to Los Angeles. Her arrival is therefore impressive, but she still appears tiny and insignificant in relation to the redwoods.

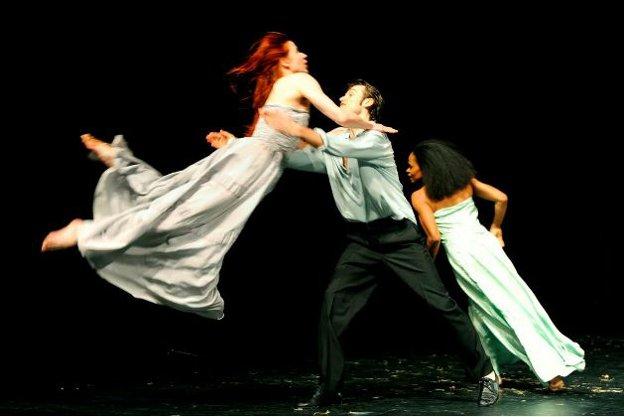

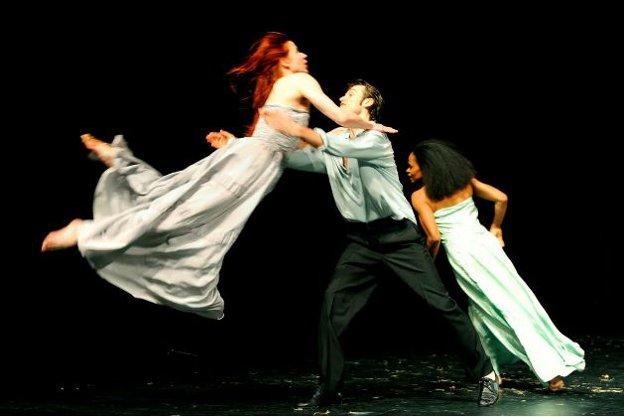

Nur Du innovatively explores this contradiction in the global image of California: its juxtaposition of rough, sublime, outsized, eternal nature with a culture in which people, and particularly women, are constrained to artificiality and ephemerality, where no woman can ever be too thin, sculpted, or synthesised. This point is made often wittily but somewhat repetitively in Bausch’s episodic drama. Suits in coke-bottle glasses stare voyeuristically at women in awards-ceremony gowns, smug expressions on their faces and unconcerned with their own appearance. A row of women sit holding their skirts up in box shapes, framing their bare legs for display. The same women flip their hair and their eyelashes for a bored, exasperated camp hairdresser clothed only in a loincloth of white mink, complete with the heads. Off to their left, a woman in a jilbab sits on the floor, refusing to participate in this ritual. A screaming fan in gaudy lingerie reacts hysterically to the possibility of an unidentified ‘he’ showing up, then is disappointed when he doesn’t –several times. Indicting the aesthetic cliches of classical ballet, passive women are carried about by judgemental men. Perhaps in retribution, a woman encloses her admirer’s head in a plastic bag, then slowly, deliberately, fills it with water. His features magnified, he sneaks offstage with her, breathing saved-up air, like a swimmer. Finding refuge in the ocean, another woman finds herself eyed from above by a giant puppet whale. Throughout all these episodes, the dancers execute the realistic yet frenetic movements and exaggerated, alternately ecstatic and tormented facial expressions long associated with Bausch and derived from the German Expressionist film and theatre of the 1920s and 30s.

Expressionism projects the characters’ psychological dramas upon the surrounding world, and in Nur Du, Bausch projects the drama of body image anxiety, celebrity culture, and the rat race upon the landscape of California. Only you, the Tanztheater seems to tell Los Angeles, are wholly consumed by these concerns. In 1996, body image was a daring theme for a choreographer to address, given its tyranny across the dance world. With that tyranny essentially unchanged since, the theme remains urgent.

It is Hollywood with which Nur Du is concerned, not, as the publicity claims, Los Angeles. On 29 April 1992, a group of white Los Angeles police officers were acquitted of the brutal beating of black citizen Rodney King, which act had been captured on videotape by a member of the public. The verdict catalysed the Los Angeles riots. This event redefined that city before a global television audience, ripping the lid off of Los Angeles’ resilient problems with institutionalised racism and vast economic disparity, and, by implication, America’s. During the riots Korean-American-owned shops were looted and gunfire was exchanged for reasons that continue to be the subject of debate. Today, the event is known in Korean as ‘Sa-I-Gu’, which translates as ‘4-29’. In experimental theatre, the zeitgeist of the riots was powerfully explored by the writer-actress Anna Deavere Smith in her solo show Twilight, Los Angeles: 1992 and in a number of other works. In Nur Du, this facet of Los Angeles takes a back seat to the shimmer of Hollywood.

There is some evidence that Bausch attempted, when devising Nur Du to examine the cultural makeup of the city. In one scene, a white male stylist dolls up a Black ingenue in a garish platinum wig; she appears to be sleepwalking. The soundtrack of mid-twentieth-century music includes non-white voices, including some Americans, such as Duke Ellington and Dinah Washington, as well as South American ballroom dance tunes and pathos-filled Indian flute music. According to the New York Times’s Ann Daly’s 1996 review, the New York premiere of Nur Du incorporated ‘prominent blackface’, which disappeared in the run’s second week. In Nur Du, the usually fearless Bausch seems to avoid Los Angeles’s complexities.