‘What is a memorial device? Is it like a pocket watch that you’ve inherited? Is it like a gravestone? Or is it more like a dictaphone – a dictaphone where you can record your memories? Is it like a marker in the sand? What is a memorial device?’

This is Ross Raymond speaking. He’s invited us here, to this theatre, to celebrate and commemorate Memorial Device. Ross wants to share his memories of the band with an audience who may or may not remember them, too; for us, collectively, to rediscover these experiences in a ritualistic manner. ‘I can’t do this without you,’ he says. ‘You are the final element of this ritual, this spell.’

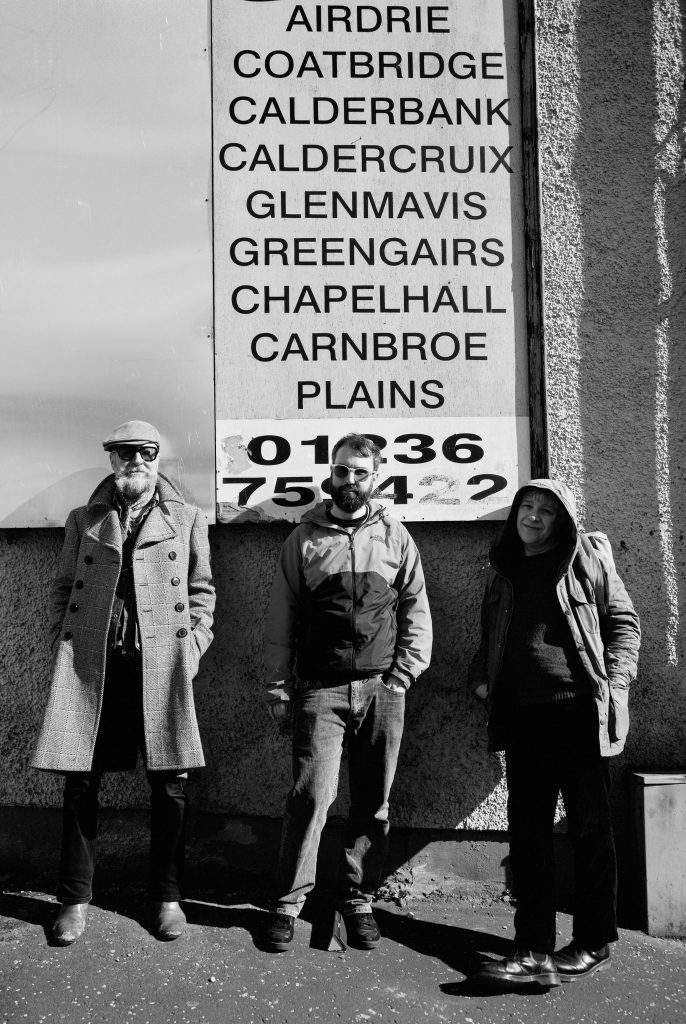

I’m sure you do remember the band, am I right? Well, if you’re of a certain age, anyway. From Lanarkshire in Scotland (Airdrie, specifically)? Made waves – industrial strength waves, to be precise – in the early- to mid-1980s? Kind of a cross between garage band psychedelia and Krautrock? Although it’s hard to pin-point their sound exactly…

And yes, after performances of the newly re-staged theatre show, This is Memorial Device, or after readings from the book of the same name that it is drawn from, by acclaimed Scottish author David Keenan, people do come up and share their memories of the band – or even suggest point-of-information corrections about which band members lived where in Airdrie, and who did what back in the day.

There’s only one problem with this: the band never existed. Or perhaps it is more correct to say that the band only exists in the imagination of David Keenan – and nowadays also in the heads of the very many people who have read the book sometime over the past seven years, or engaged with the very many Memorial Device manifestations in the real or virtual world, which include the theatrical adaptation (touring Spring 2024), the numerous fan-fiction tributes, and the band’s Twitter/X account – which has nothing at all to do with David Keenan, but has an independent life of its own. So Memorial Device have been conjured up into the world, as if by magick. They exist as much as anything else exists in our memories and imaginations. And who on earth knows where memory ends and imagination begins?

‘People do think it is real,’ says David. ‘I’m interested in how you can retrospectively affect people’s memories.’

David’s novel is a fabulous smorgasbord of first-person accounts that can be read as stand-alone short stories, but taken together add up to a history of the mysterious and legendary Memorial Device and the post-punk and alternative arts scene of Airdrie and surrounding districts in 1983 and 1984. A history, yes, but not a definitive one. There are numerous narrators, reliable and unreliable. There are conflicting accounts, and incidents are revisited from multiple viewpoints throughout.

‘The book is unfathomable,’ says David. ‘There is no bottom to get to. You don’t solve the mystery of Memorial Device. The reason This Is Memorial Device is so alive seven years after publication is that it is a living, growing entity.’ He says that readers could read the stories in any order they wished; and, gleefully approving of the fact that I found it hard to keep up with all the characters and events in the book, suggests that I re-read it from the end story back to the beginning. ‘It’s designed like an ouroboros – when it ends, you can begin again. There are multiple entry and exit points.’

I’ll say also that it all feels true to life because it is. The characters and plots might be fiction, but it’s informed by David’s own experiences growing up in Airdrie in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and his involvement in the post-punk music scene. So all the details – the houses people live in, the objects in their homes, the bands, the music, the rehearsal rooms, the venues, the weird makeshift art installations and zines and happenings – all live and breathe. There’s a real sense of emotional truth and lived experience at the heart of it all. And despite a few harrowing incidents, and the background of tough working lives and lurking violence or abuse, the overall feel is one of optimism – a ‘let’s say yes to life’ vibe that is ever-present.

‘The book is all about possibility,’ says David. ‘Things were so incredible then, post punk, especially in small working-class towns. The avant-garde was on the street – it really felt like anything was possible.’

Book, and theatrical adaptation, also serve as psychogeographic journeys to an Airdrie that no longer exists. The opening shot in the show is of a grainy photograph of David playing guitar, back in the 1980s. A photo taken by schoolfriend Martin Clark, who happens coincidentally (and what is coincidence, after all) to have come on board as the show’s video maker. Still photos are a crucial element of the show’s scenography.

‘For the past 25 years, I’ve been photographing Airdrie with absolutely no goal in mind,’ says David. ‘I’d go there and drive around and take black-and-white photos of streets and cafes and houses – often unpopulated shots. The Airdrie that exists in those photos is gone now…’

Which prompts another interesting reflection: photo as memorial device. The camera captures a second, and that image replaces any memories we might otherwise have had of that moment in time. The stage show uses those images, projected as a backdrop: ‘It’s remarkable how it has all come together’.

Sometimes we don’t know why we are doing something, but the reason emerges much later. It’s an argument in favour of instinct-led art making. As David puts it, ‘artistry is uncovering, finding out what the piece wants to be, rather than going in with a fixed idea of what it will be’.

‘OK. Why am I doing this? I’m doing it because of Memorial Device. I’m doing this to stand up for Airdrie…I’m doing it because for a moment, when everything seemed impossible, everyone was doing everything – reading, listening, writing, creating, sticking up posters, passing out, throwing up, rehearsing rehearsing rehearsing in dark windowless rooms, like the future was just up ahead… and now already it’s the rotten past, isn’t it?’ – Ross Raymond

This is Memorial Device is not your regular kind of theatrical adaptation of a novel. It’s a piece of collaboratively made total theatre that merges first-person storytelling, ritual, quirky choreography, striking visual imagery, and video and photo projection; with a musical score developed in tandem with the other elements.

The starting point came pre-pandemic when writer/director Graham Eatough mentioned to David Greig – Suspect Culture collaborator and artistic director of the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh – that he had read and loved This is Memorial Device, and would be interested in musing on ways the novel could be adapted to a stage show. Graham had previously worked with David Greig and Nick Powell on the stage adaptation of Alasdair Gray’s 1981 novel Lanark, presented at the Edinburgh International Festival in 2015.

Graham was a friend of musician Stephen McRobbie of Glasgow band The Pastels – also known as Stephen Pastel – who is a longtime fan of This is Memorial Device and a friend of David Keenan.

‘I felt that if David was on board, I’d be happy to be as well,’ says Stephen. ‘It is such an incredible novel that I wanted that affirmation from David. As it happens, Graham and David got on like a house on fire. And we all agreed that we wanted the show to keep the intensity of the book – we really didn’t want it to be lightweight nostalgia for the 1980s.’

The three worked together to create an initial workshop and a reading with music, presented at the Royal Lyceum Theatre’s Playing With Books slot at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. This experience gave them the impetus to pursue the project into a full theatrical adaption – and prompted the Lyceum to commission the work.

‘It was great to work with the author; the primary source,’ says Graham. ‘David was so generous with his material. The book invites you to reconsider your own experiences of this time… Adapting became a process of selection and amplification. The book has so many different voices in it, and so many different stories in it, that the process of selection was really challenging!’

Which is understandable, as the book has 26 different stories, mostly narrated by different characters – although it starts with Ross Raymond, would-be music journalist and zine editor, who is one of the few to get more than one story in the book.

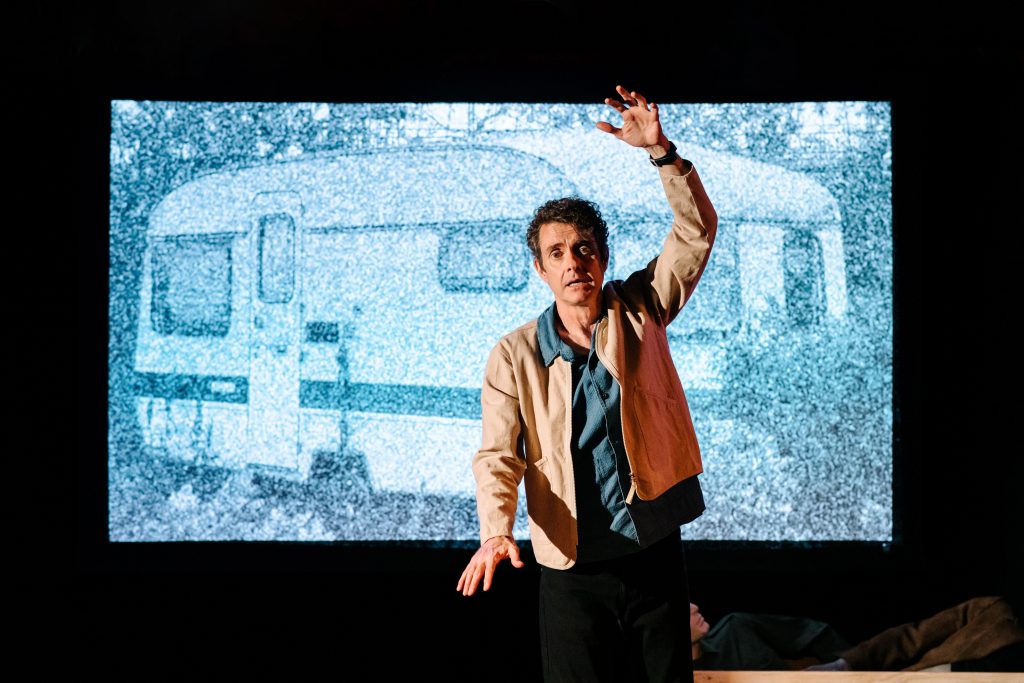

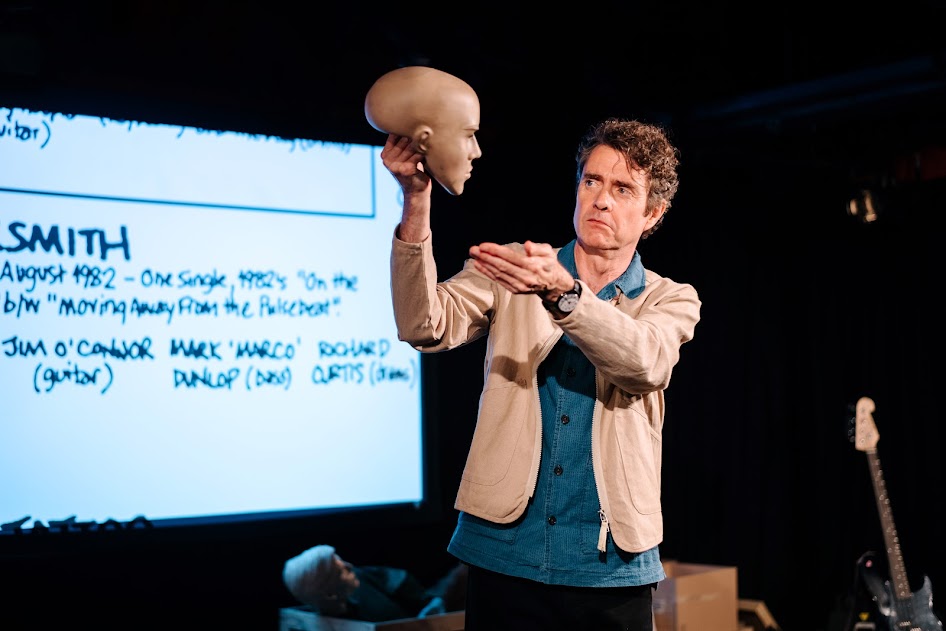

The solution was to make Ross Raymond the narrator of the theatre piece – although with some material filched from another character, Johnny McLaughlin. Ross, played by renowned Scottish actor Paul Higgins, is the only onstage performer – other characters are represented on-screen.

‘Paul is absolutely magical,’ says Graham. ‘He has been completely central to the project, and really owns it. He’s around the same age [of the story’s main characters] with a similar background and some comparable experiences. He loves the book, and he’s bought into the idea of really doing something extraordinary in collaboration with the audience for that hour and a quarter they are together.’

So, no fourth walls here! The fact that Paul once trained for the priesthood is probably an added bonus when it comes to creating a sense of communion and shared ritual with the audience. It turns out that Ross has his own agenda that is slightly different to that stated at the beginning, this revealed as the show progresses, but that is for the audience to experience and discover.

So Ross and his, and our, relationship to Memorial Device is at the heart of the show, with some other elements of the novel necessarily sacrificed.

‘A lot of our favourite stories aren’t in the show,’ says Graham, ‘because we had to be true to our chosen narrative; to put the real-time onstage storyteller Ross at the heart of the 75-minute show.’

It’s a wise decision – to give time and space to the limited amount of chosen material, rather than trying to shoehorn in too much. And although the focus is on Ross’s memories of Memorial Device, we never actually get to hear the music the band made.

‘One of the things that was always on my mind is that there shouldn’t be any music by Memorial Device in the production,’ says David. ‘Everyone has their own Memorial Device and I don’t think any music could live up to the idea people have of them in their head. Stephen and collaborator Gavin Thomson did this really well – worked around it somehow, without overtly stating it.’

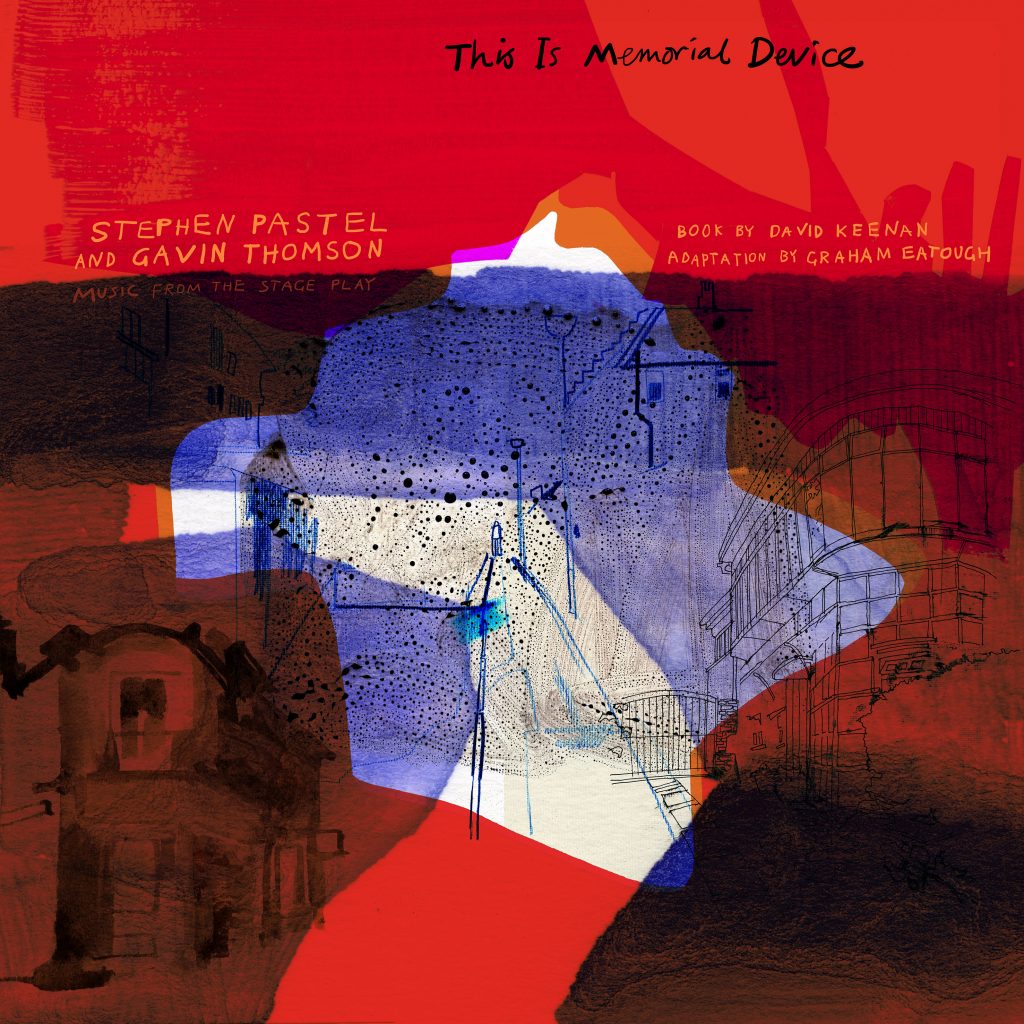

Stephen talks of the process of creating the score, which evolved in tandem with all the other elements of the production, in consultation with Graham and David – so a truly collaborative venture.

Stephen learnt, after the Playing with Books workshop, that it would be crucial to get trusted sound designer and technician Gavin, who he has worked with on Pastels live gigs, on board. And Gavin became far more than a technician:

‘Gav always does The Pastels live sound. He’s easy to be around and great with sound – and he’s a problem-solver, no tantrums. With This Is Memorial Device, I suppose we brought him in as our tech but he became a trusted and equal collaborator for me. I’d never worked with him in the studio before this, but will probably do so from now on.’

Stephen started with revisiting old cassette tapes of music he had made in the 1980s – so, music that existed before the book was even written:

‘The first music that I found that I thought fitted was made with my friend Corky [John McCorkindale]. We’d made this stuff as teenagers in his bedroom – usually when very drunk! We had this track called We Have Sex. We were trying to sound like Cabaret Voltaire, but were pretty inept. David heard it and thought it was a masterpiece!’

This and other 1980s pieces aren’t presented in their pure forms in the show, as Stephen says they are ‘too gnarly’, but have been worked into new sound compositions, created with Gavin: ‘There is a lot of beauty in the book and we wanted to bring that out.’

He cites a track called ‘The Most Beautiful House in Airdrie’, which he describes as reflecting the fact that the house is indeed lovely, but infused with an air of decay. The resulting instrumental piece is a softly melancholic, bittersweet mix that captures the essence of the house perfectly. I see the track as featuring a typical Pastels guitar sound, but Stephen clarifies:

‘Gav and I both wrote chord progressions for ‘The Most Beautiful House In Airdrie’ – both of us on keyboards away from each other, unaware of what the other was doing. Gav played the guitar on this, as I had bad arthritis on the day we recorded it. I think he played it with a nod to my style and we didn’t revisit. I really like his playing! I’m on keyboards and xylophone on this one.’

And yes, elsewhere we get dashes of post-punk, industrial and noise music – but these merging effortlessly into melodic tracks that have more in common with Ryuichi Sakamoto than Throbbing Gristle. Stephen has employed his Pastels bandmates Katrina Mitchell (vocals) and Tom Crossley (flute) together with drummer Jennifer Hamilton; and he has worked with Gavin – a self-declared synth enthusiast – on creating a score that constantly echoes and references the experimenters and garage bands of the 1980s whilst sounding contemporary.

The final track of the show is the one that comes closest to evoking Memorial Device. The theatrical conceit is that it is the last piece of music made by the band’s singer Lucas Black before his death. Lucas has made field recordings outside his home at the break of dawn, and this track, ‘The Morning of the Executioners’, has been subsequently ‘sonically dicked with’ by Lucas’s bandmates, guitarist Patty Pierce and bass player Remy Parr.

‘That final track is euphoric, uplifting, transformative,’ says David ‘Audiences have responded so well to it. It’s a big YES!’

And David likes the word ‘yes’! His favourite ever book ending is James Joyce’s Ulysses, which ends with Molly Bloom saying ‘… yes I said yes I will.’ The on-stage This is Memorial Device similarly ends with a yes – this written in by Graham without him making the Ulysses connection until David pointed it out. Another meaningful coincidence…

‘I’m learning more and more about the book by watching the production,’ says David.

A story from the book that becomes a lynchpin of the show is that of band fan and associate Anthea Anderson. She recalls the Memorial Device rehearsal room under the railway arches, where a train would pass every fifteen minutes and the whole room would shake with this industrial noise: ‘You can hear it on the early recordings’, she says. ‘They said it added to the ambience.’

She goes on to recall a landscape painting on the wall that she said seemed incongruous:

‘But when I would go to the rehearsal to hang out, I would sit and stare at it, this forest scene. It was as if I could imagine myself entering it… It was as if the music had made it open up, as if it were alive. This is only me probably, but I’d go wandering amongst the trees and the bushes along this path. It was always confused. Like, it wasn’t really happening, but I wasn’t imagining it either. It was like a portal, you know? Does this sound crazy? It was there to get inside.’

The notion of portals through which we can pass to explore the music of Memorial Device and the enigma of the band, and indeed to find out more about ourselves and our memories, is central to the stage production. In essence, we are taken on a quest of discovery – and we must commit to that quest.

This story also includes a description of the band’s music, which has made it into the show’s recorded score – a track that emerged from Stephen and Gavin jamming a response to the scene. Their music invites us to form our own impressions of the band, complementing rather than illustrating Anthea’s description:

‘Patty playing one chord on the guitar, Richard playing a mechanical rhythm on the drums, Remy alternating between these two notes on the bass… and Lucas would step up to sing and he was so handsome back then. His big lips, big Bambi eyes, his long fringe… He’d step up to sing and his lyrics would be about one thing at a time – thinking something, then seeing something, then doing something. One thing would happen after the next, like an automatic voice playing out without any personal volition…’

Although Memorial Device remain the focus, I’m pleased to learn that the story of another Airdrie band, Chinese Moon, makes it into the show…

Chinese Moon are showroom dummies. Literally. The narrator of this story is Chinese Moon member David Kilpatrick, who tells the tale of how band member Duncan’s dad, who had a high street clothes shop, agreed to let the boys appropriate the store’s mannequins, dress them in their school uniforms, and place them in the shop window with tapes playing behind them – something in between an installation and a gig. So this becomes how the band always appear when they play – absent but present. Chinese Moon appear on stage in the production as, naturally enough, mannequins.

‘The mannequins are a great way of populating the stage,’ says Graham, ‘and there are all the associations of animation and resurrection that are relevant metaphors’. Another element he highlights is the choreography (by movement director Kally Lloyd-Jones), inspired by a story in the book that describes Lucas Black leading a dance workshop in the local library. The idea of what that might be is turned into an element of ritualistic performance; a recurring movement motif that weaves through the show.

‘We invent endings, really… There is no resolution. No fixed beginning, no neatly tied up end. People have tried to read into it so much, but it was just a moment – passing.’ – Ross Raymond

So for an hour and a quarter we are taken on the quest with our narrator. From a theatrical point of view, it is a complete experience – but it isn’t one that answers all questions. There is room to think on.

‘People want art that can be solved, wrapped up, and thus abandoned – filed away in a folder marked “understood”. I’m much more interested in art that is an organic entity,’ says David.

He is confident that Memorial Device will continue to mutate into new incarnations. The book and the theatre show will live on, as will the spin-offs not authored by David Keenan – who in any case sees himself as ‘a vessel, a channel, not a puppet-master’. Having toured Scotland through Spring 2024, the show is at Riverside Studios for its London premiere from 23 April to 11 May 2024.

The album – another part of the story – is in the can, created by Stephen and Gavin and collaborators, with a gorgeous cover by former member and long-term Pastels collaborator Annabel Wright (aka Aggi).

So who knows what will emerge next. An installation, a site-responsive event, a painting exhibition, an exploration in contemporary dance, perhaps…

‘There’s that stupid expression – that writing about music is like dancing about architecture – but why not dance about architecture?’ he says. ‘You can definitely fucking dance about architecture’.

Why not indeed.

This Is Memorial Device.

To be continued… whenever, wherever.

Featured image (top): This Is Memorial Device. Photo: Mihaela Bodlovic

Dorothy Max Prior spoke to David Keenan, Graham Eatough and Stephen McRobbie via Zoom, 2 April 2024.

This is Memorial Device, adapted and directed by Graham Eatough from the novel by David Keenan, was commissioned by the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh: @lyceumedinburgh

It was developed with the support of the Stephen W Dunn Theatre Fund and originally produced in a co-production with the Edinburgh International Book Festival.

Scottish Spring 2024 tour dates:

Tron Theatre, Glasgow – 27-30 March 2024

Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh – 3-6 April

Lemon Tree, Aberdeen – 18-20 April

This Is Memorial Device comes to Riverside Studios for its London premiere from Tuesday 23 April – Saturday 11 May 2024

7.45pm (Wednesday and Saturday Matinees at 2.30pm, not 24 April) £30 (£20 concession)

www.riversidestudios.co.uk

Twitter/X: @riversidelondon | Instagram:@riversidestudioslondon

David Keenan was born in Glasgow and grew up in Airdrie, in the west of Scotland. He is the author of six novels, including the cult classic This Is Memorial Device (Faber & Faber), which won the London Magazine Award for Debut Fiction 2018 and was shortlisted for the Gordon Burn Prize. He is also the author of England’s Hidden Reverse (Strange Attractor Press), a history of the UK’s post-punk/Industrial underground, as well as To Run Wild In It and Empty Aphrodite, (Rough Trade Books), two experimental novellas, and is the co-designer, alongside Sophy Hollington, of his own tarot deck, the Autonomic Tarot (Rough Trade Books).

Twitter/X: @reversediorama

Graham Eatough is a theatre maker who also works in visual art and film. He is the writer/adapter and director of the stage show This Is Memorial Device. Other recent work includes co-writing and co-directing the book and film for the Floating Worlds project made with Dutch artist Andre Dekker on the Island of Mull in Scotland; an adaptation of Naoki Higashida’s book about autism, The Reason I Jump staged in a specially designed outdoor maze for National Theatre of Scotland; How To Act written and directed for National Theatre of Scotland; Nomanslanding a large scale floating public artwork to commemorate the First World War (Sydney Harbour, Ruhrtrienalle, Glasgow Tramway). He was artistic director of Suspect Culture theatre company from 1996 to 2009 creating over fifteen pieces of new work with the company, shown across the UK and internationally.

Stephen McRobbie (aka Stephen Pastel) co-founded The Pastels in Glasgow in 1981. They were a key act of the Scottish and British independent music scenes of the 1980s, and are specifically credited for the development of an independent and confident music scene in Glasgow. The group have had a number of members, but currently consists of Stephen McRobbie, Katrina Mitchell, Tom Crossley, John Hogarty, Alison Mitchell and Suse Bear.

The Pastels now operate their own Geographic Music label through Domino, and are partners in Glasgow’s Monorail Music shop.

Instagram: @pastelsthe

The album This Is Memorial Device by Stephen Pastel and Gavin Thomson will be released 28 June 2024.

Available from https://www.dominomusic.com/uk and https://monorailmusic.com/