At its best the work of Hofesh Shechter, director of this year’s Brighton Festival, can feel almost shamanistic – an overwhelming spectacle of pounding sounds, visceral movement and visuals. When I saw 2012’s Political Mother as part of last year’s Derry City of Culture programme, the arena was set up for a gig and hundreds of young people piled in, standing and dancing close to the stage, soaking up the atmosphere. Shechter’s gestures are writ large and accessible, bold and uncompromising: he wants to make strong statements and make them loudly.

At its best the work of Hofesh Shechter, director of this year’s Brighton Festival, can feel almost shamanistic – an overwhelming spectacle of pounding sounds, visceral movement and visuals. When I saw 2012’s Political Mother as part of last year’s Derry City of Culture programme, the arena was set up for a gig and hundreds of young people piled in, standing and dancing close to the stage, soaking up the atmosphere. Shechter’s gestures are writ large and accessible, bold and uncompromising: he wants to make strong statements and make them loudly.

In Sun, the object of his ardent scrutiny seems to be false dualisms: the over simplified dichotomy of good and evil set up by our instinctive, primitive relationships with light and darkness. It begins with a threat: ‘You will never catch us,’ growls his sinister voice, close to the mic, evoking contemporary anxieties about difference (what better catchphrase for the enemy within is there than ‘the war on terror’?), before morphing into something more ingratiating – a conventional and reassuring welcome. There’s a cheeky teaser of the end of the show, to ‘reassure’ us it will ultimately all be alright. Then a bathetic, pencil-drawn cardboard sheep on a cardboard flat appears in a powerful spotlight, to the bagpiped blasts of Abide with Me. There’s a lightness, comedy even, in these opening moments that feels intriguing. But when his opening voiceover is repeated a few minutes in, already it feels more heavy handed, a reminder we don’t need – did we hear him? Did we get it?

The first half of the piece develops through a looped sequence: courtly dancers evoke studied postures and gestures, occasionally disturbed by ripples of something more primitive, but overall their movement and costumes (they’re dressed by Christina Cunningham like eighteenth century harlequins and courtiers) evoke the civilised order of the harem or medieval court. They are here to entertain us, gently. The court dissolves and, in blackout, the sheep multiply, and then they dance, bouncing and gambolling with balletic irony. ‘Look how simple we are!’ they seem say, before a 2D wolf appears, sidling closer with discomfiting menace. The tense stand off is interrupted by a bloodcurdling scream from the front row and we are plunged into ear-splitting darkness, where hellish, dimly lit figures flit and roil about the stage. Finally, the balm of the sun – cleverly created by a simple upstage lamp casting a rich amber disc onto a sheet held midstage. In later episodes the wolf and sheep are replaced by more contemporary figures of threat – colonisers, bankers and hoodies. The sequence plays with false dichotomies – order versus chaos, blasting sound versus silence. Difference and perceived threat trigger the collapse from one into another: it’s significant that we never see the threatening figures actually attack – it’s the onlooker’s scream of fear that ruptures the scene. But the repetition, again, flattens out the meaning, like the cardboard cut outs of the enemy Shechter is presumably satirising. The rich, ambiguous poetry of his movement is reduced to a pretty simple message – that those we think of as the enemy may well not be. Hey! We, the middle class audience quietly consuming the show, might even be the bad guys, complicit in some pretty terrible deeds done in the name of our comfort! Do you feel like you’re a sheep yet?

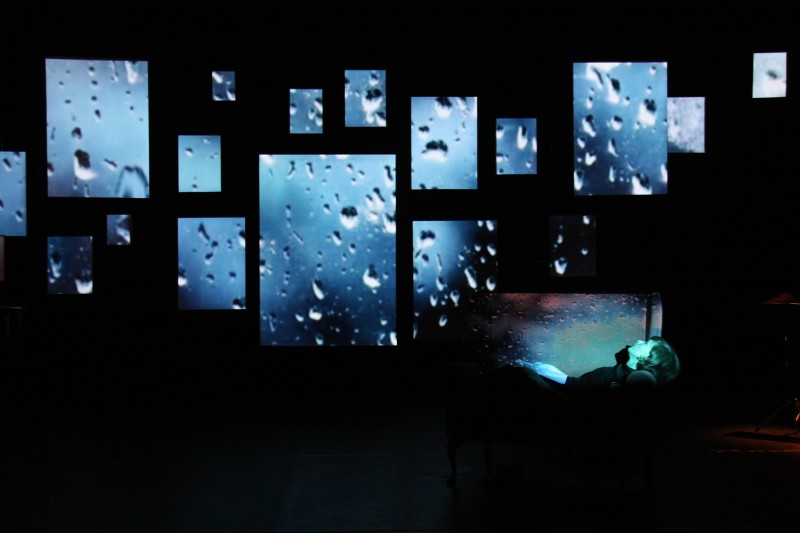

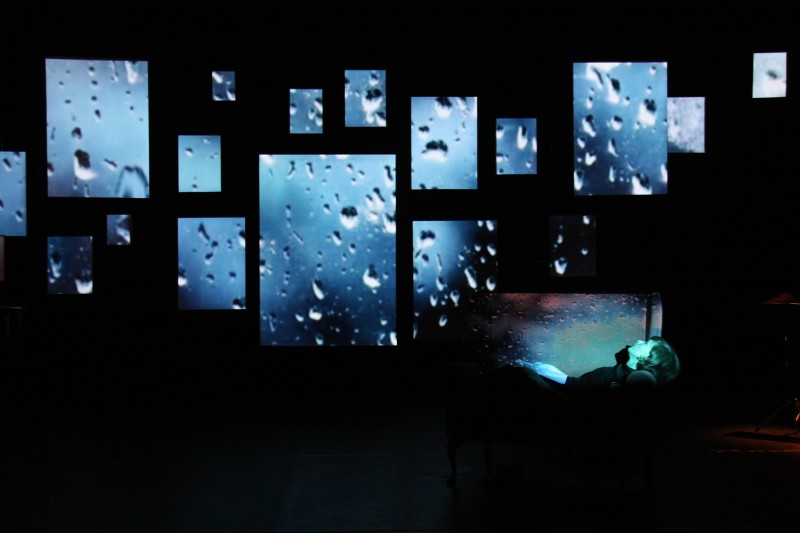

Later sequences where this tight structural form breaks down offer greater interest: there’s a ravishing image of man in thrall to the power and beauty of light, as embodied by designer Merle Hensel and lighting designer Lee Curran’s stunning firmament of pendant tungsten bulbs, whose rich amber glow and glass reflections seem to ripple above him as he chases, or perhaps follows, their swirling movement with his fingertips. The significance of the standalone sequence where some of the female dancers stripped down to their underwear passed me by, however. Sun worshippers perhaps? The visuals as a whole are gorgeous: a stony, granular upstage wall shifts through an array of painterly tones courtesy of the incredible lighting design, transforming the stage picture from the feeling of Breughel right through to Bosch.

Shechter’s choreography is densely patterned and intriguing, jewelled with lovely moments and images, almost too rich a meal to fully absorb through this 70 minutes. And so we fall back on the structural ‘message’ and it is a polemic, shouting at us. I am left feeling that Shechter’s approach to his audience is rather too closely informed by his approach to his work – which he composes, choreographs and often dances: one of absolute control. But when everything is conducted at full volume (and despite the moments of silence, make no mistake, this is a performance whose ideas are expressed almost entirely at that pitch) we stop being able to hear any subtlety. His politics and ideas feel heartfelt; I hope he can start to trust us a little more, and realise that there’s no need to shout.