There are certain institutions whose very existence feels reassuring. Often NGOs, they are the embodiment of certain principles and their ambitions toward fostering peace, international collaboration or environmental protection give the comforting impression that ‘something is being done’ if even if you yourself are too busy to get directly involved. The UN, and particularly news announcements of the deployment of UN peacekeeping forces (an oxymoron I have never noticed before) has always been, for me, one such institution. But, in these two linked productions, David Leddy shatters these illusions, weaving together extensive research with his richly imaginative approach to new writing to expose the UN’s role in corruption and power grabs through sexual exploitation in conflicts, recent and historic, around the world. The result is both shocking and compelling.

There are certain institutions whose very existence feels reassuring. Often NGOs, they are the embodiment of certain principles and their ambitions toward fostering peace, international collaboration or environmental protection give the comforting impression that ‘something is being done’ if even if you yourself are too busy to get directly involved. The UN, and particularly news announcements of the deployment of UN peacekeeping forces (an oxymoron I have never noticed before) has always been, for me, one such institution. But, in these two linked productions, David Leddy shatters these illusions, weaving together extensive research with his richly imaginative approach to new writing to expose the UN’s role in corruption and power grabs through sexual exploitation in conflicts, recent and historic, around the world. The result is both shocking and compelling.

In Horizontal Collaboration, the setting is fictional, though plausible: an unnamed African country, plagued by inter-tribal warfare, primitive perspectives, and a bloodthirsty history. Though the references feel convincingly of the now the action, centred around the family of a dictator’s wife and their grapples to attain and retain power through marriage and assassination, has the ruthless outline and epic resonance of Greek tragedy. ‘It’s biblical,’ several characters repeat, yet into this old testament world of power-plays and revenge enters the UN, not as an intermediary moving things forward, but absolutely as another player in the fight.

Leddy articulates a profoundly effective form through which to articulate this story. In the bowels of a UN building, a secret tribunal is being conducted: an assassination has occurred, war crimes committed, the murky contexts must be investigated. Its testimonies bring us the voices of the educated wife of the warlord Judith K, her mother Mary X, her servant and half sister Grace M and the UN doctor interviewing them, read on each performance by new actors who uncover and invest in the story at the same pace that we do. This allows for some lovely reversals and discoveries and also a rather acute sense of powerlessness (ours and theirs) – the narrative rolls forward like history, its destination unknown. The rigid structures of UN administration, here embodied by a precisely ordered and symmetrical mise en scene where, through matching laptops and neatly rolled scarlet cables, horrific experiences can be filed as coldly numbered testimonies and every shocking reference to UN crime and corruption bracketed by caveats about the bias and unreliability of its speaker. It perfectly encapsulates the limitations of large institutions and their ability to cover up corruption and mistakes. We are witnesses to the UN (re)writing history and the production is at is strongest when it resists dressing or poetically reorganising its material for dramatic effect, allowing story, characters and their clever frame to play out according to their own relentless rules.

Judith K is a disarming protagonist. Intelligent and cool, her inscrutability does allow her to take her place as a centre of power within the play. But the show as a whole goes much further in deconstructing various systems of power. Our awareness of casting choices heightens the gender and racial power structures at play on and off stage. Both productions are concerned with rape and sex as power play, racial and sexual prejudice. Here the spareness, elegant structure, and thoughtful form intensify our encounter with these ideas. Conducted entirely thorugh the staid stage picture of four bureaucrats sitting behind a long table and lit only by practicals – anglepoise lamps and computer screens – whose light, as the story progresses, gradually diminishes (Fire Exit are fantastic at structuring ideas through production dramaturgy), this is rich and provocative play whose testimonies linger as glimpses of possible and disturbing truths in a world that seems a lot darker than when I first walked into the theatre.

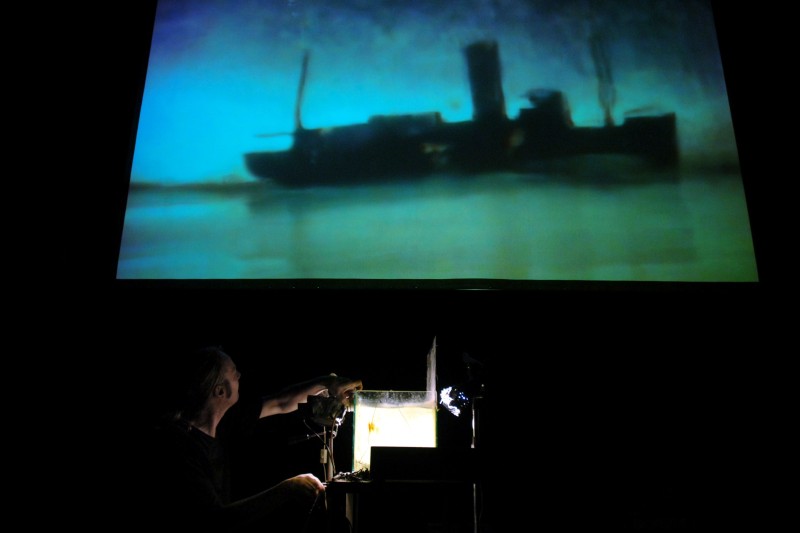

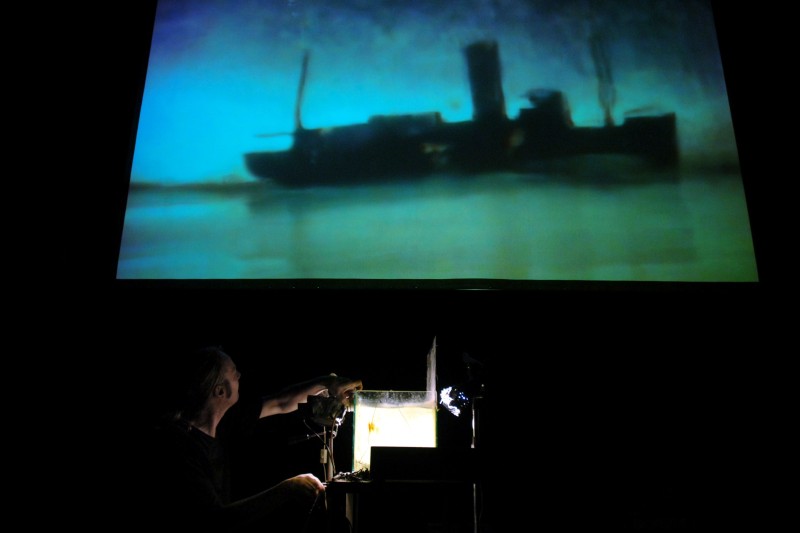

In counterpoint to this, City of the Blind is a full and detailed journey expanding on many of the play’s ideas: a Russian novel to the play’s poetry. It has a similarly original approach to form: a set of six episodes streamed to your own device and comprising linked fields of video, audio and photographs. Now we are in the belly of the beast and all of this ‘paperwork’ reflects the experiences of a forensic analyst investigating the trial of crimes concealed by and within the UN. There is a conscious incorporation of the real – each episode is backed up with a host of articles and essays that demonstrate the corruption discussed in the story is a live issue and passing references are made to recognisable international figures such as Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

The story clashes this hyper-reality with mythology – our protagonist Cassandra suffers from a conversion blindness – stress can affect her eyesight profoundly, and these mythological connections are increasingly hammered home in threatening story books she starts receiving to warn her off her investigation. This theme is perhaps an attempt to theatricalise and stylise a form which, though compelling, can’t quite stand up to comparisons with big budget films and TV shows that explore some of the same conspiracy thriller memes. It’s intriguing to encounter the story through your phone and laptop, but in a world when much big budget media can also be consumed this way it doesn’t quite make itself different enough to avert direct comparison.

What both productions self consciously share is a desire to muddy the water between a person’s morality and their actions: ‘Why do good people do bad things?’ Judith asks and is asked, repeatedly – the question itself starts to feel naive. The amorality of desire is a theme woven throughout City of the Blind and the more expansive and flexible form here allows us to delve into characters’ private sexual worlds as well as their actions on public record. The hypocrisy of drawing a line in the sand about where judgement should be made becomes more apparent. The other recurring statement that spans both shows is ‘I have absolutely no idea what happens next’ – deliciously metatheatrical in Horizontal Collaboration and an admission of powerlessness or suspense in City of the Blind. What is encapsulated is the heightened sense that our own actions have the possibility of initiating change (an idea, of course, intrinsically linked to performance). For me the underlying impact of this double bill is, in fact, a call for action, as well as a call to re-think.