Cartoon de Salvo is celebrating fifteen years of ‘surreal, unpretentious, swashbuckling theatre’. This perfectly describes Hunting the Shark, an entirely improvised play created on the spot on 5 April 2012 as part of Made Up‘s run at the Soho Theatre. As the title suggests, Made Up will yield an entirely different tale each evening, inspired by an audience member’s randomly selected offering.

Artistic director Alex Murdoch performs with company co-director Brian Logan and associate artist Neil Haigh as sea-faring men, monkeys, limping Irish shark-hunters, and a castaway in the middle of the Pacific ocean. Armed with a harp, guitars, double-bass, violins and a SpongeBob SquarePants child-size drum kit, the improvised band The Adventurists both score and drive the atmosphere, as well as helping to create surprisingly effective songs.

Improvised shows have a habit of sliding into a stand-up / Whose Line is it Anyway? comedy schtick. Cartoon de Salvo purposefully set out to eschew this result, and with a title such as Hunting the Shark it’s a challenge. Haigh, Logan and Murdoch rapidly respond to each other’s offerings and, amidst some perfectly timed comedic lines, they gently weave a complex story of long-lost love, rivalry and regret over a slightly too long ninety minutes.

The challenge, and joy, of improvised work for an audience member is working out the story yourself, and the knowledge that the performers don’t know the answers. It creates a stirring liveness, and permits us to actively engage with the craft of the storytelling itself. I found myself creating twists and turns, trying to pin down who the shark should be, as we gently sailed towards the climax. It can also be a frustration. It’s difficult to truly empathise or invest in characters who are being created on the spot in a story that we are well aware does not yet have an ending. Cartoon de Salvo quietly manage to avoid this.

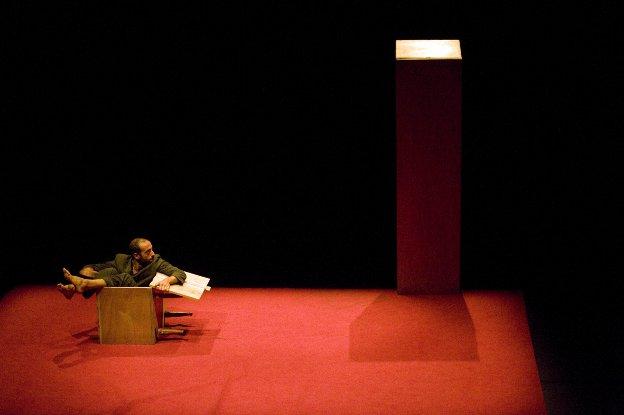

The company are incredibly generous performers, completely invested in supporting each other’s ideas and building upon the tiniest of details. The performers’ utter belief in their characters and their willingness to dive into darker and more abstract moments entirely make Made Up more than a night of amusing but forgettable play-acting. About a third of the way through, Haigh summoned a spotlight and began quietly singing ‘My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean’ whilst he mimed dressing and posing in front of an imagined mirror. Intimate, slightly sexual and intriguing, it became the crux of the plot, and elevated Cartoon de Salvo’s ‘making up’ high above the generic improv show. Here’s to another fifteen years of their swashbuckling.