Junction 25 is a young people’s performance company that puts young people’s voices firmly into the centre of contemporary performance. For their 2013 Edinburgh show, they’ve created a piece of interactive work which sits close to my heart having made a piece about a very similar subject matter: success, failure and how we are set up to achieve (or not as the case may be). The show was co-devised (with the young performers) and directed by Jess Thorpe and Tashi Gore of Glas(s) Performance.

We’re seated in two long rows in front of oversized 30-metre long school desks with a wide galley between us. Our names are called out and we diligently put our hands up: ‘Here!’ If anyone’s not quite loud or emphatic enough they are asked to repeat themselves. The fourteen-strong cast are all dressed in white shirts and black trousers, with some personality thrown into the shoes whether it’s Nikes or Doc Martins. An hour-long (mock) exam follows– we have a full-on exam paper in front of us, and the first three questions we’re asked to answer are genuinely terrifying.

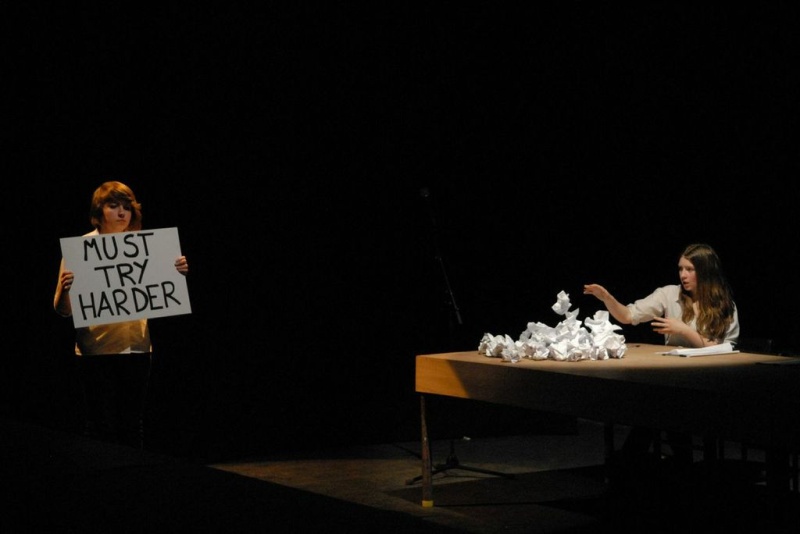

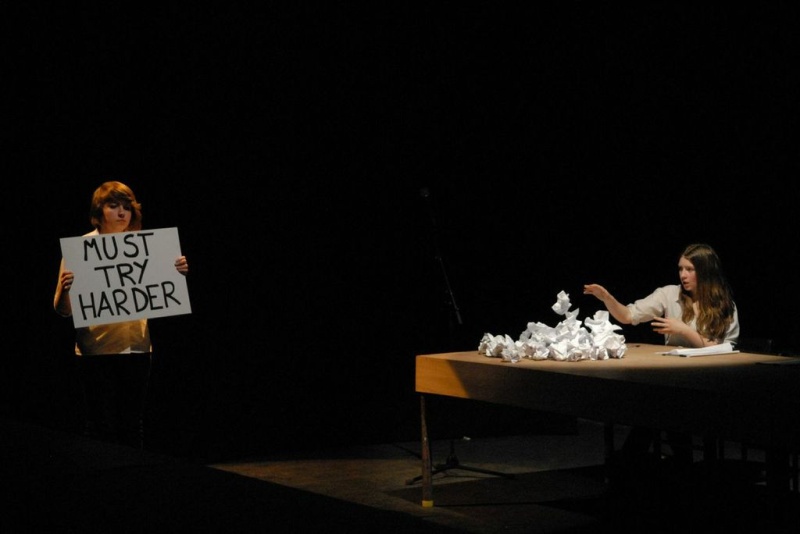

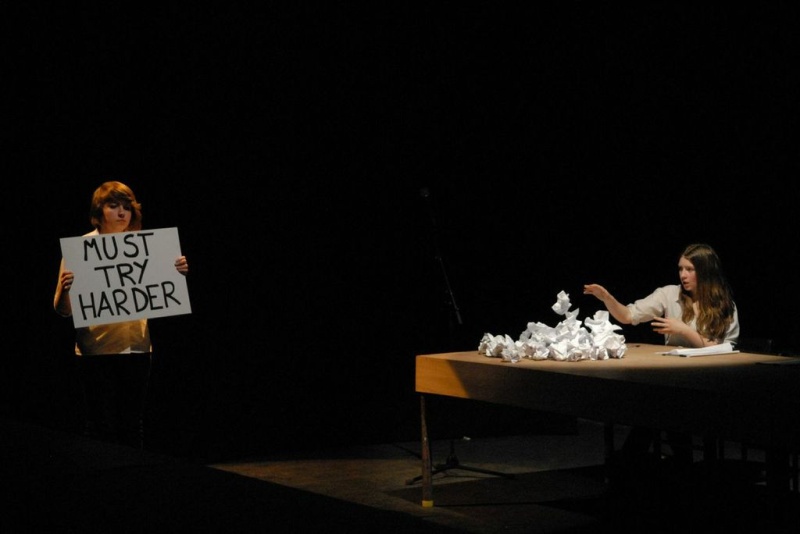

We meet the young people involved in dribs and drabs, often through report-card style overviews. Lily is often late and needs to concentrate more; Jack needs to improve or he’s not going to succeed… An audience member takes part in the multiple-choice exercise entitled ‘Who wants to be a successful human being’ in which she has lifelines that include: Google, calling the Samaritans, or asking a mate. Section B of the exam requires us to write an essay based on a picture of a maze, before one young girl is picked out for admitting she’s cheated and subjected to a humiliating walk of shame with a sign that reads ‘Must try harder’.

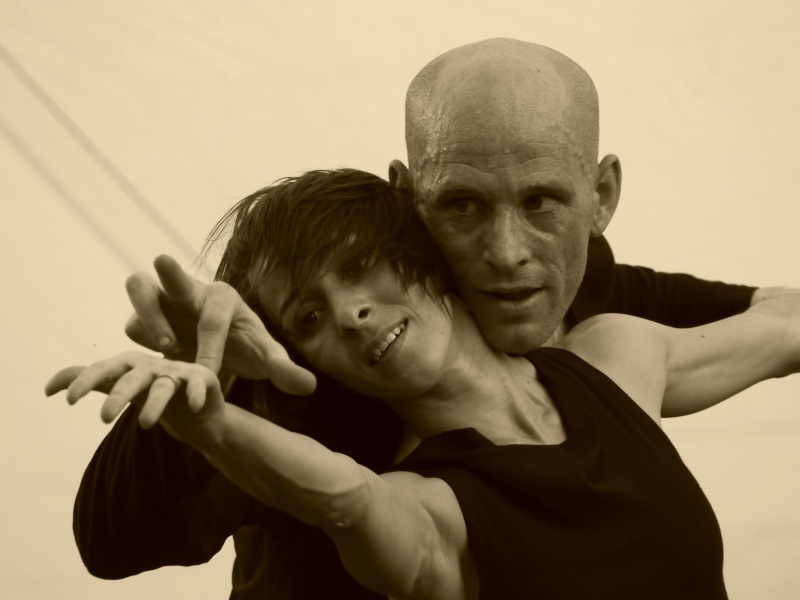

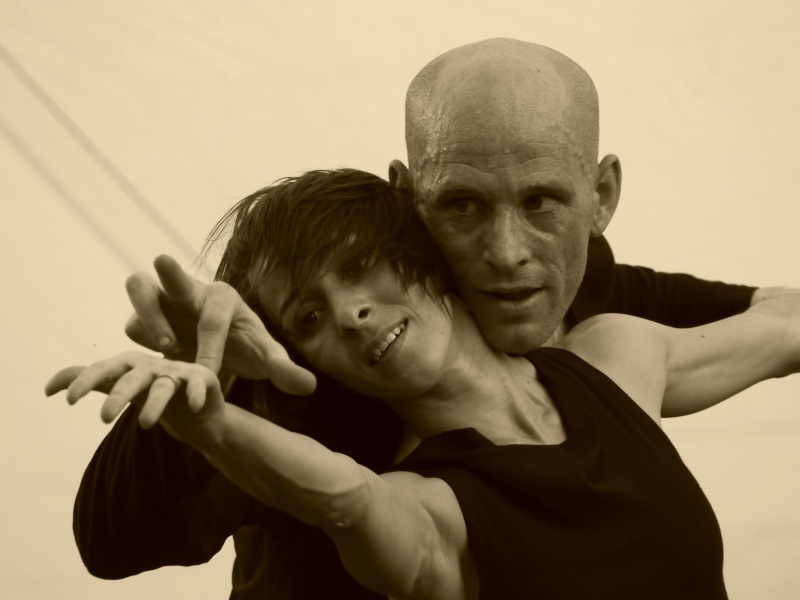

Interspersed between the test and report cards are lovingly created movement sequences that lift the show out of the classroom and into our hearts. A line of paper stars is hung across the space and the desks at which we sit become catwalk-like runways for the ensemble to race each other, walk a tightrope, hug, hold hands, and cartwheel. It’s a gentle and honestly performed musing on the realities of school-life from the fun to the friendship to the stresses and loneliness. Elsewhere, the gang push themselves forward up and down the gangway in the centre of the room. Slowly one falls, followed by another. The rest power on through as another falls and picks themselves up again. We’re all in the race of life, and sometimes we fall behind.

One of the cast reads a letter he wrote to the Cabinet Secretary for Lifelong Learning asking questions like “Why can some raise their voices and others can’t?’ He had received a reply, but you’ll have to go see the show to find out what they made of it. Despite the piece feeling like a massive critique of an education system that asks people to conform and learn without knowing why they’re learning, Junction 25 finish with a sweet and uplifting ending as the previously wayward Jack figures out what he is good at – it’s an ending that lifts the heart and reminds us that we can find our own way in spite of the stifling systems that govern how we are valued.