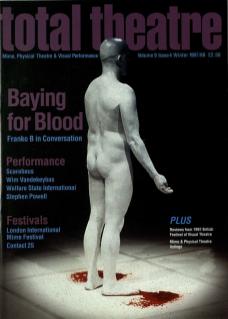

The last time I saw performance artist Franko B was at the ICA. He was hanging from a meat hook at the end of a show in which he lay naked in a pool of his own blood. In other shows Franko has cut his skin with a scalpel, bled from open wounds, vomited blood, and had his lips stitched shut with gut. Meeting him face to face for the first time was going to be a nerve-racking experience. What would he be like at home?

Franko B's South London flat clearly doubles as his studio. On the VCR a video of one of the ICA performances is playing. In it he is daubed from head to toe in thick white paint and blood is dripping from the veins in his forearms. Franko is making a copy to send to a friend. All in a day's work. The ordinary becomes extraordinary in Franko's flat: along the length of the sitting room wall a metal urinal acts as a handy book shelf; old fashioned wheelchairs provide the seating and medical detritus – syringes, swabs, assorted shiny clamps – decorate every available surface.

I would feel disconcerted, except Franko is the perfect host; making espresso and providing the guided tour. He talks rapidly, his guttural accent a combination of native Italian and South London. Franko left Italy in the early 80s. He was living in a squat on Railton Road at the time of the Brixton riots. Later in the decade he studied Fine Art at Camberwell. For the past five years he has been building a reputation as a performer who endures the sort of pain that you or I would run a mile to avoid.

Of course artists have been performing radical acts on their bodies for years. Since Duchamp shaved a star into the hair on his head in 1919 and declared himself an art object, a succession of artists have put themselves into situations of palpable physical risk in the name of art. During the heady days of the 1970s, American performance artist Chris Burden had himself shot, imprisoned in a tiny locker without food for five days and nailed to the roof of a VW Beetle. The previous decade witnessed a flurry of bloody performances in Vienna. Artists known as the ‘Viennese Actionists' staged events in which they disembowelled dead animals, smeared themselves with bodily fluids and toyed with razor blades, nails and scissors in frenetic scenes of simulated self-harm. The public were simultaneously revolted and fascinated. The work was banned.

The viewing public's fascination with extreme risk and the vicarious pleasure to be derived from watching a performer in pain continues into the present decade. French circus troupe Archaos played havoc with chainsaws and pyrotechnics and sold-out their death-defying shows. Camden's Roundhouse recently hosted the Circus of Horrors in which, for the price of a seat, punters could watch 'strong men' stick needles through their cheeks, lift heavy weights from their testicles, and swallow fluorescent tubes. Clearly the public has a taste for blood. But what are the performers trying to prove?

Franko insists on his own sanity. His art school tutors thought he might need psychiatric help, but perhaps they were too eager to dismiss as 'madness' that which they struggled to understand. Franko admits his art is a product of his own psyche: ‘The work is a product of who I am.’ But he suggests that his bloody performances are simply manifestations of psychological impulses common to us all: ‘I'm like everybody else, I don't think that I'm special. My work is made up from my insecurity, my feelings of inadequacy and so on.’ But insecurity doesn't make us all take a knife to the nearest vein. Or does it?

In some ways Franko's performances express a self-destructive drive which is shared by many and often manifested as alcoholism, substance abuse or bulimia, for instance. Self-harm can seem therapeutic, as Franko admits: ‘The performance is to do with survival. What I do in performance makes me feel totally free... This obviously goes some way towards making me feel better in myself. I am doing something which allows me to feel that I have some kind of respect, of dignity; feeling that it's worth me living.’

As well as providing personal catharsis, Franko's work is an impassioned plea for unrepressed self-expression. It started as a protest over the prosecution of a group of gay men for acts of sadomasochistic sex in the controversial 'spanner' trials. That these acts were performed consensually and in private raised the thorny issue of the right of the state to intervene in the private activities of the individual. Franko got his boyfriend to carve the words 'protect me’ with a scalpel into the skin on his back. His message was clear; he needed to be protected from society and its draconian laws, not from the lovers with whom he might chose to practice SM sex.

Through the act of cutting his own skin and drawing blood, Franko asserts his right to control his own body and is liberated from rules imposed by those in authority. His fear of powerlessness, he explains, stems from an unstable family history: ‘I was brought up in an orphanage for seven years and then I lived with my mother for two and a half years, and then I was taken away from my mother by the state and I was put in a Red Cross Institute in Italy for battered kids and I was there for five years.’ He explains that his work helps him cope with the insecurity, because through it he recreates himself as his own independent being: ‘I am nobody's baby. I don't want to play your game. I don't want to be assimilated into a club. The idea is simple, I am not what you want me to be. I am trying to do things for myself.’

Nonetheless, Franko is cagey about providing too much biographical detail, because he wants to stress the universal themes in his work. He is also quick to remind me that he is making art; a fact that often gets overlooked by commentators who obsess about the psychosis of the artist at the expense of the art itself. He is after all an image-maker, as he explains: ‘I am concerned with beauty. You can use anything to make beauty.’ Furthermore, he points out that he needs an audience for his work. He is not interested in committing acts of self-mutilation in private: ‘I have come to the conclusion that I will not perform these acts just for myself. I am making art, I am making paintings, these are available for people to consume.’

As an artist his tools might be unorthodox – he has abandoned paint and canvas in favour of the body, skin and blood – but his intention is not to shock. ‘If people want to be shocked, they get shocked. It's what they want,’ Franko says. Furthermore he doesn't want physical pain to become the point of the work, so he cuts himself off-stage. To explain, he points to a scar in his chest, the product of a deep knife wound inflicted backstage at one of the ICA performances: ‘I would never do [this] on-stage, because I don't want my work to be about that. It is not about the action it is about the language, it's more about the metaphor.’

But surely Franko must be putting his own personal safety at risk in performance? His answer is disingenuous: ‘No more than if I were to cross a road without looking and ran the risk of being hit by a bus. It's not about risk.’ However, he does explain that his doctor has advised him to do no more than three or four performances in a year. ‘I lose over a pint of blood in performance,’ he says by way of explanation. ‘Once I've bled,’ he goes on, ‘there's not much else I can do. To me bleeding is the ultimate. Eventually I will have to stop performing because I cannot do anything else. The only other thing I can do is to open myself up, which I've been wanting to do for a long time but which for practical reasons I can't.’