On 30 October 1984, in the unlikely surroundings of The Ralph Thorsby Community Centre, a myth was born. It was here that the fruits of Impact Theatre Cooperative's collaboration with Russell Hoban were premiered and The Carrier Frequency first saw the light of day.

Founded in 1978, Impact Theatre Cooperative comprised Pete Brooks, Claire MacDonald, Steve Schill, Graeme Miller, Tyrone Huggins and Richard Hawley with Nikki Johnson (now Nikki Cooper) joining in 1982 and Heather Ackroyd the following year. The company were, in Richard Hawley's words, ‘tribal, stylish and radical’. As Nikki Cooper explains, ‘They viewed themselves as cultural guerrillas with a mission.’

In some ways Impact Theatre Cooperative were a part of the same University of Leeds milieu that produced bands such as The Mekons and The Gang of Four. Like countless post-punk bands, Impact Theatre Cooperative initially set up and funded themselves through the dole. It is probably fair to say that, by the time of The Carrier Frequency, Impact had outgrown Leeds. But it had in some way provided a sympathetic environment in which to start their work.

To the already fertile Leeds landscape Pete Brooks, Claire MacDonald and the others brought their own obsessions. ‘We were interested in fantasy and science fiction,’ explains Claire MacDonald, ‘particularly J.G. Ballard, Anna Kavan (whose novel Ice we adapted in 1979) and Angela Carter, as well as children's literature which mapped imagined places... Myths and epics combined with road movies, war films and Ealing comedies went into the mix, along with heady doses of structuralist art and film theory which led us to address acting and action, real time and narrative structure.’

Simon Vincenzi, who designed the set for The Carrier Frequency says, ‘Most of [Impact’s shows] were based on myth. And that myth was Paris in 1920 or post-war Germany. They were based on received ideas of another life. They would use huge literary influences unashamedly because that's what they were interested in.’

Writer Russell Hoban, like Impact, was interested in myths, language and parallel worlds. Hoban admired Impact's work. He had written a warm review of the company's 1983 piece No Weapons for Mourning. So, when he met Pete Brooks and Claire MacDonald shortly afterwards, it is perhaps not surprising that they decided to collaborate. ‘Working with Russell Hoban presented us with a new challenge,’ says Nikki Cooper. ‘We had to respect some of his working methods and not keep discarding his text. At one stage, later on, we were going to forget about text altogether, but then we decided to work with its constraints. God knows what Russell made of us all. My diaries depict him as incredulous for much of the time. I think he just couldn't understand why we didn't just get up and get on with it.’

Curiously, at the time, Russell Hoban noted in his diary, ‘I like being with Impact and I'm learning from them. I'm learning more about art. I'm learning more about what doesn't need to be spelled out brick by brick, learning more about inviting action by putting the right elements next to each other.’

From the start, The Carrier Frequency was an extraordinary show. Nikki Cooper remembers: ‘The Carrier Frequency was different from previous (Impact) shows in two respects: firstly it didn't change very much from the opening night to the final performance – usually our shows changed enormously in performance. Secondly, it was the only show that was, I suppose, robust enough to let other people perform in it. Three of us didn't complete the run and several different people took over.’

Andrew Quick, now a lecturer in Theatre Studies at Lancaster University, says of the show: ‘I remember vividly the first performance of The Carrier Frequency in that strange venue... seeing it raw, rough, actually not perfect by any means... Some performers, you could see almost struggling to get through the actual performance which created extraordinary energy.’

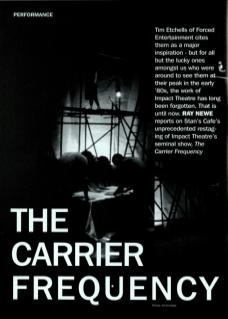

Forced Entertainment's Tim Etchells wrote of the show in a recent issue of Time Out: ‘It stays burnt on my retina – desperate, madly comical and deep in poetry.’ Reviewing the show at the time in Performance magazine, Steve Rogers wrote: ‘In theatre such as this it would not be unreasonable or surprising to see people fly.’

Given The Carrier Frequency existed in a post-apocalyptic landscape, it is appropriate, not to say ironic, that its final performance took place in Warsaw on the 26 April 1986 – the night Chernobyl exploded. After The Carrier Frequency, Impact Theatre Cooperative began to disintegrate. ‘The Carrier Frequency was sort of an implosion,’ says Vincenzi. ‘Implosion is probably the wrong word but I remember watching it on the first night and thinking, well, that's probably the last one.’

Whilst Claire MacDonald remembers: ‘Impact was a group of people who made work and threw it away, who gave parties rather than made videos and who lost most of what we should have kept... in romantic retrospect, we were full of beautiful wasteful gestures – but I don't think we would have had it any other way.’

Since then, The Carrier Frequency has persisted as fragment and rumour. In the awed testament of those who saw it; in the poorly discernible images left on various videos of the show – all of questionable legal status – and, perhaps, in the work that Impact's members and audience have made since and still make.

All this changed in April this year, when the theatre company Stan's Cafe – none of whom had seen it first time round – decided to restage The Carrier Frequency. Throughout the nineties, Birmingham's Towards the Millennium Festival has presented artworks connected with a decade of the 20th century. 1999 is the year of the 1980s. Stan's Cafe director James Yarker says: ‘I couldn't abide the idea of this thing happening with absolutely no reference at all to any theatre activity that wasn't based on a script.’

Stan's Cafe is by no means a fixed company. For this production, performers from companies such as Frantic Assembly, Reckless Sleepers, Vincent Dance Theatre and Talking Birds were drafted in to restage The Carrier Frequency. ‘I didn't want it to look as if Stan's Cafe were attempting to take possession of... a show that means a lot to so many different people,’ states Yarker. ‘I wanted to share the discovery of this project with artists from a range of companies who I suspected may, wittingly or not, have been influenced by Impact.’

Restagings of another company's work are rare, if not unheard of, in the sphere of Live Art and it called for an unusual rehearsal method. ‘We spent the first week working very closely with the original text and video documentation, doing a very literal learning process – gesture for gesture, inflection for inflection. In the second week we barely looked at the video and worked on the performance as if it were our show. Although we had the full cooperation of the original company, we resisted the urge to quiz them much about their production. We wanted to work it out ourselves,’ explains Yarker. The video from which Stan's Cafe worked did not include all of the original devising cast members, which raises interesting questions about where, exactly, this production stands in relation to the original show.

I think, ultimately, that Stan's Cafe's The Carrier Frequency is a footnote to the original. Even given the performers' best diaphoretic efforts and the tempest created by Miller's original soundtrack, The Carrier Frequency 99 is a polite and respectful affair.

Yet Stan's Cafe's production also serves to shore up the myths around the original; its very existence a testament to their power. Why else would a company, described in one of their press releases as specialising ‘in creating new theatre works of intelligence, beauty and humour', be interested in recreating a fifteen year old show? ‘I'm sure that it wouldn't have crossed Impact's mind to restage say, Kantor's work,’ says Vincenzi. ‘Culturally, I find it quite depressing.’

‘Thank God our art doesn't last. At least we're not adding more junk to the museums. Yesterday's performance is by now a failure.’ – Pete Brook

If, indeed, Stan's Cafe's restaging represents a failure of their imagination, as Vincenzi appears to suggest, then it is a depressing state of affairs. However, not all of those involved in the original production are disparaging about the restaging, For the writer, Russell Hoban, the Stan's Cafe production is simply a logical continuation of Impact's work: ‘Once you start a repetitive pattern, whether of two-dimensional design or of action, it continues to infinity. You can put a graphic boundary or a temporal one around it but the thing keeps going unseen beyond that boundary until it's made visible again. The action of the original production has been continuing on its own since 1984 and now new actors step into it and move with it.’

Given its themes of myth and memory and its own mythic status it is indeed appropriate that of all Impact's shows, perhaps of all the experimental theatre made in the 80s, The Carrier Frequency should be the one revived. Watching Stan's Cafe's The Carrier Frequency, it is impossible to avoid the feeling that the show itself somehow demanded restaging. ‘Here we are at the end of the second millennium and the “end of days” is still just around the comer,’ continues Hoban. ‘I don't remember the precise state of the world in 1984 when The Carrier Frequency was first performed but the planet is certainly no safer now.’

James Yarker seems less sure of his motives: ‘We didn't have clearly stated objectives at the start of this project. We wanted it to happen. We wanted not to get pilloried for it. We wanted the original company not to disown us or our version of the show. We wanted lots of people to see the project and be inspired by it. We wanted not to be bankrupted by the procedure. We wanted to place a marker in the Millennium Festival for experimental artists who, because of the nature of their work, have not been absorbed into the classical repertory... Ultimately, maybe we just wanted to experience a live version of The Carrier Frequency. I think we achieved most of these things.’

This clamour of demands is confusing yet, amidst the fog, it appears to demonstrate a desire for tradition and the establishment of a canon, both of which are already in existence in the cultural monolith that is mainstream theatre. Yarker wants the respect of those whom he perceives are his elders; he wants to spread the word and to stake a claim for his inspirations. This is Stan's Cafe's gift to those they admire.