‘A wilderness of desolation with miles of ugly, vulgar, shoddy stuff, without one touch of imagination, one message to history'. This is how King George IV described Walworth after a visit in the early twenties. Today, travelling the Walworth Road, staring blank-eyed from the top deck of a bus, it is easy for those unfamiliar with the area to sympathise with his sentiment.

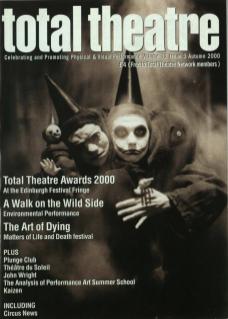

Artist and founder of Plunge Club, Rene Eyre knows better, and last month staged a twenty-four hour 'ambient event' – Theatre of Memory, Theatre of Myth – at one of London's best kept secrets. Behind the unexceptional frontage of Walworth Methodist Chapel lurks Clubland – one of the country's first youth clubs – a product of the imagination, stamina and charisma of the diminutive preacher, James Butterworth.

Butterworth began his ministry in Walworth in 1922 having been appalled by a declaration made by one of the local slum-dwelling boys that he would rather commit another crime and return to reform school than stay in Walworth where there was nowhere to play. Butterworth determined to build a haven where local children could play and create. By the end of the twenties, a new chapel and club stood on the site of the old Wesleyan chapel and, during the thirties, slum property was purchased and demolished to build a gym, theatre, art studio and workshops.

Clubland opened in 1939 only to be destroyed two years later by German bombs. Butterworth undertook a massive post-war fundraising campaign to rebuild the chapel and club. In the hidden courtyard five hundred donor stones, sold at £100 each, bear the names of luminaries of sport, cinema, theatre and politics whose contributions led to the rebuilding of Clubland. Consequently the place resonates with a bygone glamour that's strangely at odds with its prosaic South London setting.

It is difficult to believe that this potent brew of mid-twentieth century celebrity could be so thoroughly hidden. Yet, these days Clubland is seldom used. 'It's so strange,' says Rene Eyre, 'because this place found me.' Approached by Southwark Council to stage an event for the millennium, Eyre already had the idea for Theatre of Memory, Theatre of Myth and was searching for a suitable location in which to stage it. ‘I was looking for a place with big and small spaces and both indoor and outdoor locations,’ Eyre tells me. In the run up to New Year’s Eve 2000, the present Reverend of Walworth Methodist Chapel found his congregation swelling and feared that by December 31st he would be unable to fit them all into the Chapel. Consequently, he invited Eyre to discuss the possibility of installing a live video playback so that those members of the congregation unable to get into the Chapel could listen to the service outside. Her excitement at having discovered this neglected gem is still undiminished.

The idea behind Theatre of Memory, Theatre of Myth came from an investigation into the history of memory, as Eyre explains: 'Greek orators had a memory trick in which they imagined a building and filled each room with a resonant object. The orator would then move from room to room – the object serving to remind them of the next stage of their speech.' Clubland's rooms are already full of resonant objects, and remain very much as they were. Responding to the space, Eyre invited artists to make work that drew upon the history and mythology of Clubland or their own memory and mythology.

Thus, in the canteen, artist Victor Mount staged a nostalgic event that drew on his own memories of youth clubs. The contribution of Dartington College graduate Sarah Butterworth pulled together both strands of the suggested remit, for she is founder Jimmy Butterworth's grand-daughter and used the opportunity to create a shrine to her grandmother. Where underprivileged youth once played cricket on the roof, artists' group Syzygy created a huge kite. In the shell of the gym Eyre performed My Father's House, an autobiographical piece about her father inspired in part by an etching of him that she had done when only nineteen. 'My dad would barely talk to me and it was an attempt to communicate with him,' she explains. 'I always start work with an image that somehow embodies the piece that I'm going to work on. Finding the etching was sort of spooky. I thought, "Oh God, I've been doing this all along really. I’ve been pursuing my dad and trying to get to grips with him and understand him all this time.”’

My Father's House was a barren landscape of earth and fetid pools, a veil of tears was projected and an outsized hessian doll represented the deceased patriarch. Eyre describes it as 'creating an alcoholic reverie and nostalgia for Ireland that every immigrant feels'. This is not the first time that she has turned to her family history as source material. In 1993 she created Say a Little Prayer, a dance piece about her mother. ‘A lot of my work has been autobiographical,' she concedes, ‘and I'm sort of ashamed that I'm constantly pulled back into memory and exorcising my family but I've given up fighting it.' Her art is a kind of alchemy where she transforms the base material of her childhood into performance, and her family history – at least the way she tells it – is so full of violence and abuse that it makes an embarrassing inadequacy of the word ‘dysfunctional'.

Given the show's themes of memory and myth, it is worth a look at the history of the Plunge Club itself. Born in Brixton in 1994, Plunge Club was a response to funding problems. Eyre's own work – informed as it was by her background in fine art illustration and dance (she has degrees in both) and her enthusiasm for theatre and music – was becoming more difficult to categorise and, therefore, fund. 'This was pre-Combined Arts, I think, or just on the cusp of it,’ she says. ‘Categorising my work was becoming increasingly difficult, so myself and a bunch of Brixton artists decided to create our own context, a club night once a month – not banging techno and hard drug abuse (although there was quite a bit of that) but rather seasons of monthly platform events.’

Plunge Club provided an umbrella for as wide a range of artists as possible – established and neglected artists, students and chancers of every stripe responded to the monthly themed evenings. 'It was a chance to fail, to take the plunge. It provided an opportunity for established artists to migrate to different forms. A lot of healthy throwaway work was created that would not be seen and done again,’ remembers Eyre. 'We all pulled together. We had no money, we did it for love. All the artists were complicit. There would always be a meeting to discuss how your work would be programmed, it wasn't just "come in, do the work, fuck off again".’

One of the Plunge Club's great strengths was its informality. 'It allowed everyone to take chances that they wouldn't have in a more formal setting – it wasn't going to ruin their career, but it would inform their practice. Artists are on something of a treadmill of applying for funding and making a piece and getting it all right and its very pressurised. If you do appear to squander your money on a piece that doesn't work, then the likelihood is that you won't get funding again.'

In addition to monthly events in a club environment, Plunge Club staged larger-scale events at Nunhead Cemetery and the Oval House. These days, however, it is more of a banner for occasional spectacles such as the one at Clubland. Still, Eyre is not yet tempted to lay it to rest, despite the mountain of administrative worries it presents: 'I need the warmth of a community in which to make work,' she explains.

In a sad footnote, Theatre of Memory, Theatre of Myth may well have been the last chance the public had to see Clubland in its present state. Modernisation, and even possible demolition, is due next year. Walworth will be robbed of a remarkable tribute to working-class culture and energy as Clubland itself passes into myth and memory.