As Butoh began as a reaction to the westernisation of Japan after the end of World War II, it might seem strange that there is currently such a huge upsurge of interest in the artform among western performers. But on closer investigation, it can be argued that what has traditionally been considered as an entirely new and uniquely Japanese theatrical language, was in fact partly born out of an exchange of both eastern and western traditions.

In Japanese 'Butoh' literally translates as 'stamping dance'. The formal term for the artform that first emerged in Japan in the 1950s is Ankoku Butoh, which translates as ‘dance of darkness'. Hijikata Tatsumi is widely regarded to be the founder of Butoh. He created his first performance, Forbidden Colours, for the Japan Dance Festival in 1959. It was a frenzy of stamping – an erotic, sacrificial ceremony in which a live chicken was killed by strangulation. One of Hijikata's sources of inspiration for Forbidden Colours was the French theatre-maker and essayist Antonin Artaud. According to recent research Hijikata Tatsumi, who did not understand French, responded to Artaud's screams on a recording of the radio play To have done with the Judgment of God, which he acquired in the late 1950s. He would play the tape over and over again as inspiration for his performance. Many of Hijikata Tatsumi's associates went on to form their own companies in the 1960s and 70s and thus created the basis of a Japanese Butoh movement which still exists and tours internationally today. These companies most notably include: Sankai Juku, Carlotta Ikeda and Ariadone, Musaki Iwana and Eiko and Koma, to name a few.

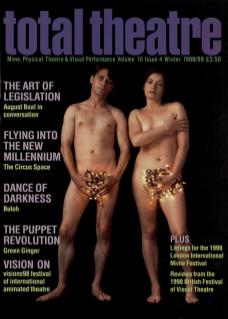

To define Butoh is in itself a mammoth task. There are many misunderstandings and preconceptions obscuring what is essentially a deeply spiritual artform. Butoh is in some ways not just an artform, but a philosophy and a way of life as well. The commonly held view amongst those not in the know, is that Butoh is a dance style performed by naked actors smeared in white body paint. This is the Butoh cliché: the shaven headed androgynous dancers, with contorted limbs and bandy legs; the agonisingly slow and deliberate movements; the uncompromising and provocative sexual imagery. No wonder it's known as the 'dance of darkness'. The Japanese dance critic, Nario Goda, sheds more light on the definition of Butoh, when she explains that: ‘In all of us there is fifty percent darkness – a dark place that we know nothing about. It is that darkness that Ankoku Butoh strives to preserve. It is something we do not understand completely.’

Every Butoh company, or solo performer, has a completely different style. Much Butoh does not even begin to resemble the stereotype of the artform described above. Carlotta Ikeda, who was recently seen at The Place with her company Ariadone, passionately believes that ‘Butoh belongs to no style, it refuses all stylisation, wipes away all techniques and therefore all aesthetic concepts that they generate’. However, there remain many commonly held misconceptions about Butoh. One of these is that it developed as an artistic response to the nuclear attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The gap of over a decade between World War II and the Japan Dance Festival of 1959, would seem to explode this myth, as Butoh dancer Masaki lwana points out: ‘Over ten years passed between the bomb on Hiroshima and the beginning of Butoh, so who said Butoh was anything to do with the bomb? The image of the body in Butoh performances were thought to resemble the images of Hiroshima victims. But they just looked the same that's all, it is simply a coincidence.’

The commonly held view amongst those not in the know, is that Butoh is a dance style performed by naked actors smeared in white body paint

Artaud was not merely an influence on Hijikata Tatsumi's work. He is also cited as an inspiration on the work of the experimental theatre director and poet, Tarayama (founder of the Tenjo Sajaki group), and in the work of the Gutal Group, both of whom were active in Japan in the 1950s. In addition to Artaud, there are further links between the Japanese performers of the 1950s and contemporary western performance and art movements of the 1950s and 60s. Parallels can be drawn between early Butoh performances and the Happenings of Allan Kaprow and Fluxus, which characterised the emerging performance art scene in the United States in the 60s. The work of John Cage and Nam June Paik, which embraced perceptions of body, music, space and time, also bears comparison. Additional western influences on the emerging Japanese artform include: Dada and Surrealism; the literature of Genet; Bataille and Lautremont; the painting of Francis Bacon, Willem De Kooning, Bosch and Breugel; and of course German expressionist dance as taught in Japan through teacher Kazuo Ohno.

The Japanese Butoh company Sankai Juku, which arrives on British soil this month to perform at Sadler's Wells, is arguably responsible for the commonly held image of Butoh as an angry and subversive artform. The company, under the Artistic Direction of Ushio Amagatsu, gained widespread notoriety for the artform when it first performed in North America in the mid 1980s. Butoh was to become ever more associated with danger and risk-taking, following Sankai Juku's famous performances in which company members were suspended from ropes, at heights of up to 80 feet, above city streets. Butoh's reputation as an extreme artform that blurs the boundaries between art and life was sealed during a fatal performance in Seattle in 1985 when one of Sankai Juku's performers plunged to his death during a show.

Sankai Juku's latest performance Shijima, promises to be less risky and more contemplative. It is described as a religious ceremony in seven scenes, which begins and ends in silence. In it, a huge white mural imprinted with human shapes, envelops the stage. With shaved heads and white painted bodies, five male dancers, robed in chalk-white dresses, perform a series of simple, controlled movements like ancient sculptures brought to life. Clearly the company still make work which conforms to the commonly held stereotype of the Butoh performance. Some detractors claim that Sankai Juku has been single-handedly responsible for deepening the misconceptions about Butoh and claim that the company has 'aestheticised' the artform to unhealthy and often damaging ends.

In the UK the Butoh flag is being flown by the London Butoh Network, established in 1997 to promote Butoh and to organise training opportunities in London. The Network was established by Marie-Gabrielle Rotie and Fran Barbe, both of whom trained as dancers and now teach and perform Butoh in London. Rotie combines visual art, Roy Hart Voice techniques, release-based improvisation and Butoh in her solo performance works which to date have included: Plaits, Angel Animal and Scapula. In her own words, Rotie is on a ‘crusade to promote European Butoh’. She is interested in the existential qualities of the artform and, far from considering Butoh to be a uniquely Japanese theatrical language, sees it as touching on the universal human condition: ‘We all experience life, birth and death regardless of cultural origin - Butoh tries to approach those things.’

Both Barbe and Rotie are concerned to educate audiences about Butoh in order to correct the many ‘pre-conceived ideas and superficial observations’ from which the artform suffers. Fran Barbe, who first came across Butoh in 1992, found the artform instantly liberating. ‘It opens up so many possibilities for me as a performer and choreographer,’ she says. ‘I had been seeking an escape from technique for its own sake and Butoh showed me an approach which put ideas and emotions first, and form and technique in their service.’ Rotie and Barbe teach classes in Butoh at the Drill Hall which are attended by a varied selection of actors, physical theatre practitioners and non-performers. Interestingly, few dancers are numbered amongst the participants. One individual who attends the class is actress Karin Heberlein. Heberlein explains that ‘Butoh is interesting for a performer because it gives you a new way to open your body – new physical vocabulary’.

Clearly for Japanese and European Butoh practitioners alike, there is no simple definition for such a complex and varied artform. That Butoh is an intense and soul searching journey for those performers who practice the form, is perhaps the one unifying link. Isamu Ohsuka, of the company Byakka Sha, explains that Butoh is a process through which the dancer can learn to awaken the subconscious in performance and find a way to connect with some universal human truth. ‘When humans are in the womb it is said that the development process they go through is like the process of human evolution. For me Butoh is when those memories from the womb are re-awakened.’

The 'dance of darkness' might perhaps be better described as a journey toward enlightenment.

Emi Slater is Artistic Director of Perpetual Motion Theatre.