Sitting in BAC’s café on a sunny afternoon awaiting Punchdrunk is a rather odd experience. The venue is a working building; yet meetings are taking place, coffees drunk and deals struck in the midst of– well, normally one would say ‘the set’ but this word is insufficient – the carefully-built environment of Punchdrunk’s Masque of the Red Death, a show which has been running at – or more correctly in, through, and around – South London’s prime fringe theatre venue for the past six months.

And, as director and designer Felix Barrett later puts it, this isn’t a case of the illusion of theatre exposed to the daylight – I’m sitting here within a ‘heightened reality’. The paintings I am looking at are real paintings, lovingly created by associate artists (‘120 people have contributed to this show’ says Felix). The lazured paint on the walls, the metal fireplaces, the lanterns, the tables, and upstairs the beds, the wardrobes, the clothes in the wardrobes, the desks, the letters in the drawers in the desk, the perfumes in the glass vials, the wine in the bottles, the sumptuous silk cushions – it is all ‘real’. When you ‘see’ the show, you also touch, smell and feel the show. The level of detail is astonishing, and ‘in the atmosphere whether you notice it or not’ as Punchdrunk producer Colin Marsh says. Which is why even bits of the rooms that can’t be properly seen are still painted and decorated.

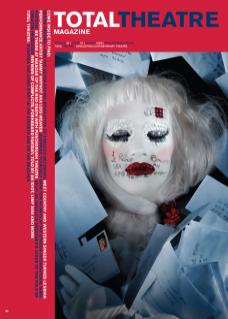

There’s no ‘backstage’ here – except for backstage at the Palais Royale (a show-within-the-show that is a delightful centrepiece of the production) and of course that backstage is as real as everything else: feathered fans and ballet pumps discarded by dancing ladies, Pierrot costumes awaiting their owners, and gentlemen magicians awaiting their cues.

No surprise then to learn that Felix Barrett’s early work included both installation and performance: it was just that he saw these as separate paths he could take as an artist. Studying drama at Exeter, he was fortuitous to have Steven Hodge as his tutor. Hodge is a founding member of the revered site-specific company Wrights & Sites, and it was he who allowed, nay, encouraged Barrett to see that ‘real’ environments, installation and theatre could all work hand-in-hand. He thus created a version of Woyzeck (a text popular with visual theatre-makers!), and a ‘show’ that involved driving audience members off into the forest alone… It was this early work that set the scene for the model of practice that Punchdrunk have made their own: a model in which the audience are ‘immersed – plunge them in!’ as Felix says gleefully.

When Felix moved to London, the next major phase for Punchdrunk started when a producer working for dance agency Independance (Colin Marsh) was on the lookout for an interesting collaboration for one of his artists, choreographer Maxine Doyle. He had a ‘tiny pot of money’ for this work, and it was he who brought Doyle and Barrett together. ‘I spent a lot of time watching her’ says Felix, ‘even though I’d done some dance classes in the past, I felt completely out of my comfort zone. We both spent time observing each other; when we started to work together, it was straight in on the rehearsal floor. It is a genuine collaboration; we bounce off each other, have a shared vision but different paths. It was clear from day one that we both believed that the light is as important as the sound, which is as important as the architecture, which is as important as the movement.’

Even when the work starts from text – and in fact most of the company’s work takes its inspiration from classic texts: Shakespeare numerous times over, Marlowe for Faust, Edgar Allan Poe for Masque – the company start with action. I learn that their usual starting point is a game of hide and seek in whatever building or space they have chosen to site their work – a disused factory for The Firebird Ball, an empty warehouse in Wapping for Faust, a Victorian old town hall (BAC) for Masque. Felix talks of the thrill of allowing the building to dictate the evolution of the show: Masque is ‘ back to the purest form of how I want to ‘write’: get a place, get a date and let the place create the show’. At BAC on that very first devising session with the cast it was lights off and off you go… apparently some cast members were so spooked by that first experience that there are still corners and hidey-holes they avoid. ‘Plenty of ghosts in that building’ says Felix.

So in their initial devising process, the cast kind of pre-figure the audience’s experience of entering the space expectantly but with some trepidation, wondering what they will find. How then do the company feel about the very unusual relationship that is fostered between the cast, the audience and the environment they share?

‘We’ve learnt so much over these past few shows that we feel confident we can really play with it’ says Maxine. Although it is a crude assessment of their roles in the company, we could say that Felix is more involved with the creation of and placing of objects in the work; Maxine with the physical dynamics between the cast, and the movement of bodies – cast or audience – around the space. ‘’The cast of Masque have become really good at moving people around’ she says. And talking of the structure and pace of the show, ‘We learnt from The Firebird Ball that a show needs to have a crescendo, so for Masque we worked on the ending first (as Poe did).’

Despite Masque being in some ways a continuation of models established in other productions, it is constructed in a fundamentally different way, with each main cast member given an Edgar Allan Poe story to make their own. Everyone has a mission, everyone their own separate story to tell within the bigger picture. Poe’s tale of the decadent Prince Prospero and his cohorts, who hole themselves up in a castle to escape the plague rampaging outside, forms the nucleus of the show, but audience members familiar with his work will take pleasure in discovering characters from The Fall of the House of Usher, The Tell Tale Heart and The Black Cat, to name but a few. ‘It was challenging to dig into Poe, to go to the darkness at heart,’ says Maxine.

At this point, we talk about the company’s earlier show at BAC, The Yellow Wallpaper, based on the book of the same name by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Maxine describes it as ‘an epic in a tiny space’ (it was set in BAC’s attic). This story of misogyny, loneliness and creeping insanity was presented for one audience member at a time. Maxine says that the experience of developing such an intimate performance piece, and the ‘microscopic attention to detail’ this involved really informed their large-scale work: ‘In Faust we learnt to get the balance between individual experiences and manipulating the space’.

After the experience of being in a massive, empty five-floor warehouse for Faust, setting Masque in BAC has meant learning to use a more contained space for a nightly audience of 250 visitors – and to make good use of the things which can’t be moved, and which tell stories of their own: fireplaces, marble staircases, skylights, rickety attic stairs and all. Yet it was a challenge they very much embraced. They were helped in the initial devising stage by architect Steve Tompkins, who is working with BAC in an ongoing collaboration called ‘The Playground Projects’ which, BAC director David Jubb says, ‘seek to invent the future of theatre spaces through the collaboration between artist, staff, audience and architect.’ So collaboration has been at the essence of the making of the work: the collaboration between Felix Barrett and Maxine Doyle, the two artistic directors of the company; with their creative producer Colin Marsh; with BAC producer/director David Jubb; with architect Steve Tompkins; with the 120 associate artists, makers and cast members; and last but not least – with the audience.

The fruits of that collaborative process are paying off: Masque goes from strength to strength, with the BAC run now extended to April. Punchdrunk are taking Faust over to New York later this year, and have plans to re-create this and other works at various places worldwide (including Australia 2009). So they are more than happy with way things are going.

But at the same time, there’s a desire to challenge expectations and try something radically different with the next show. What might that be? ‘An opera!’ says Felix. And who knows, that might just happen. Watch this space, as they say.

The Masque of the Red Death continues at Battersea Arts Centre, London until April 2008. See www.bac.org.uk

For more on the company, including the plans for New York and other new ventures for 2008–2009, see www.punchdrunk.org.uk