'The easy bit of ventriloquism is how to talk without moving your lips.’

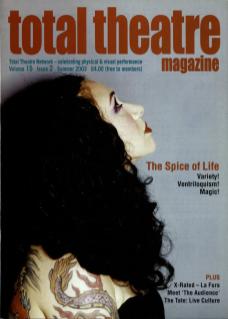

Ken Campbell's Children of Bisu is a paean to the dying art of ventriloquism – an art which he is on a mission to revive.

Bisu, legend has it was an African pygmy and a courtjester to the Babylonian King Pepe in 5000 BC. He had perfected the art of gastromancy whereby he could draw spirits from beneath the ground up into his sphincter and through to his stomach. Once inside, the spirits, good or bad, could mock and parody the king and his court, much to the amusement of all. So well-loved was Bisu and his talking stomach that when he died he was declared a god, the god of gastromancy. And so began the history of ventriloquism – also giving rise to the meaning of the word, which is taken from the Latin venter loqui, to speak from the belly.

As an accompaniment to the show, and as part of the International Workshop Festival in collaboration with Brighton International Festival, Ken Campbell held a ventriloquism workshop at the Gardner Arts Centre – to recruit prospective children of Bisu to the dark art of talking ventriloquially.

Ventriloquism's great secret is that talking without moving your lips is not that difficult; twenty letters of the alphabet can be said without movement. So one method would be to script everything you do, avoiding the six difficult letters. However, the dedicated ventriloquist would master the hard letters: M, P, B, F, V and W. Campbell has a mnemonic sentence for this:

'Who dared put wet fruit bat poo in our dead mummy's bed; was that you, Verity?’

When it comes to learning how to speak these letters, there is actually very little to know. Here is a quick summary of the basics: The M is a humming NG, the P a Tork, the B is a Dora G (hence Gottle of Geer), F is TH, V is also a TH and W is huh-oo. Simple as that! The trick is to speak these letters as though you have 'secret lips' inside your mouth.

Campbell tells us that by the end of one day we will be able to ventriloquise. And with daily practice of at least ten minutes in front of the mirror to correct any movement of the lips, known as residual flutter, and with dexterity of the inner mouth, we could become competent ventriloquists. However, doing that is only the first step on the path to becoming a ‘real ventriloquist'... the ultimate goal is advanced ventriloquism.

‘In advanced ventriloquism you should look like you are listening to what – in fact – you are saying,' says Campbell – you have given life to the ventriloquial (vent) puppet and it exists apart from you. He argues that ventriloquism is very different to usual puppet manipulation. Normal puppets, marionettes, etc., are great for the purpose of storytelling, but they don't tell a story ‘in the here and now'; they will be recreating the story, whereas there is an immediacy to the material you can develop with vent puppets. As Campbell says: 'You are the straight element of the relationship, the star, the comedian, is the puppet. It has been tried the other way round but I can't tell you who they are because they never became famous.’

The trick is to find out who you are in relationship to the doll. An example Campbell gives is Nina Conti, daughter of the actor Tom Conti, who went to his classes and discovered a latent talent for ventriloquism. Within six months she had cracked advanced ventriloquism by discovering an attitude of embarrassment towards the doll and upon this attitude she could build an act.

Campbell explains that coming to a ventriloquism workshop is more instruction than any of the legendary ventriloquists ever had. They simply saw someone doing it and went home and worked it out for themselves. So it is unusual to have it taught, but it ‘is necessary at the moment because people in Britain have stopped doing it'.

As for why anyone should learn ventriloquism, Campbell believes that there is a myriad of uses. For example, as we see demonstrated on stage later, a Shakespearean soliloquy could be delivered ventriloquially (it perhaps makes more sense for Hamlet to be pondering on whether to be or not without moving his lips!). Or, as he also demonstrates in the show, ventriloquism might have been used in more superstitious God-fearing times during the exorcism of demons. With the help of his ventriloquising assistants he artfully illustrates this by bringing an audience member on stage and asking him to kneel on all fours. The assistants stand over him and then battle to drag a cursing, blaspheming demon out from the backside of the afflicted volunteer. Fanciful stuff and definitely designed for comic effect, but the theory of ventriloquising priests is compelling, and even if it is apocryphal it is a great example of the dramatic possibilities open to you if you can speak without moving your lips.