Trees are one of our most essential symbols; their twisted, aged forms are sacred to all human culture. In India, women place offerings at the foot of the banyan tree in hope of fertility: in Kyoto, Japan paper is hung from branches to attract good luck, and in Catholic Europe pilgrimages are regularly made to the sites of great trees. The oldest recorded living tree is 12,000 years old and most trees live into their hundreds. They are one of the cornerstones of our ecosystem, yet we clear land as it suits us.

The debate is as topical as ever – tree dwellers versus road expansionists, Swampy versus the bulldozers – our headlines are filled with battle stories. Surprising then that few theatre companies outside of theatre-in-education choose to address environmental concerns of this kind. Perhaps it's because political theatre no longer sits comfortably in the post-Thatcher world. Or perhaps it's that, in this saturated media age, all we really want from shows is a little diversionary entertainment. Either way political theatre is virtually dead. Still, the issues remain and it would be a shame for theatre to give up its political resonance. One answer may be to try gentler tactics, to communicate with metaphors and stories.

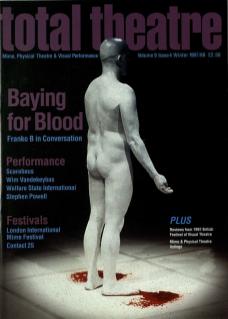

This is the approach being taken by street theatre company Scarabeus (the name comes from the scarab, a large dung beetle, regarded as sacred by the Egyptians), whose abstract shows are a visual mix of aerial and stilt work, framed by lighting and sound.

The company was formed in 1988 by three performers: Daniella Essart from Italy, Soren Nielson from Denmark and Kevin Alderson from Britain (who has since left). To date they have produced three shows which have toured to the car parks and shopping malls of Europe. Their first show, Ballet-tico Fantastico, was a parody of ballet's prima donnas, Syzygy (1991) was a ritualistic piece which drew on the myths and legends of different cultures, and Fata Morgana, their latest piece, was a theatre, circus and dance hybrid which explored the theme of 'mirage’.

Philosophically, Scarabeus are committed to raising the quality of outdoor work and to performing to a non-theatre-going public: at least 90% of their audience for any particular show will be locals, many of whom will have caught the act while out shopping.

Their new show Arboreal, which will premiere this spring, is the first issue-based production that the company are tackling. It will focus on the nature of our relationship with the environment and in particular the way in which landscapes, and specifically trees, shape who we are. It was inspired initially by a reforestation programme in the Highlands of Scotland.

There was a time when the forests of the Scottish Highlands were as great as those of Central Europe. This changed as early as the Middle Ages when through economic necessity, trees had to be felled for fuel and building, and land cleared for grazing. The forests became patchy as overgrazing destroyed new saplings and prevented them from regenerating. The situation was exacerbated in the eighteenth century, during the Clearances, when local landlords introduced vast numbers of sheep. Nowadays, forests are threatened by commercial forestry and tourists who, straying from designated paths, erode the top soil.

One scheme dealing with these forestry issues is the Crocach Crannah Project – a small reforestation programme in Skerray, managed by the local arts officer, Gavin Lockhart. The project, on the north coast of Scotland near the Kyle of Tongue, aims to remodel man-made landscapes into their original form. One idea has been to cut a peninsula into an island, another to plant 13,000 trees. When Scarabeus learnt about the project they approached the community for permission to do a show based on this work. 'They liked us,' explains Essart, the artistic director of Arboreal, ‘but they asked us not simply to do a piece of publicity because that would be against their philosophy. Instead they asked us to come back with a good metaphor.’

Essart proposed a piece based on The Baron in The Trees, a novel by the illustrious Italian author Italo Calvino. Calvino, born in 1923, was an avowed opponent of Fascism in Italy. During the war he joined the resistance movement and later became a committed member of the Italian communist party. His stories are inspired by folk tales and many have a fantastical quality. The Baron in the Trees is the tale of Cossimo, a twelve year-old nobleman living in the eighteenth century who, witnessing the destruction of his local landscape, decides to live the rest of his life in trees. ‘Central to the story,’ says Essart, ‘are characters with big ideals who stick to them. They are happy but they pay for it.’

The company have now been working on the piece for over three years: developing the show, securing funding and engaging collaborators. Those who will join them for this project are Gavin Lockhart who will provide video images for the piece; Giuliano Palmieri, an Italian composer, who will use sensory techniques to enable those on stage to provide the motor for the soundtrack; Claude Coldy, a choreographer who has developed the ‘Danse Sensible’ Technique based on osteopathy; Jerome Aussibal, a mountaineer; and Muir an artist and designer.

During the upcoming year the show will be staged both indoors and outdoors and will be performed on a set of artificial trees (which in the outdoor version will be set alight at the end of each performance).

It will tour to alternative venues and outdoor spaces, with the company continuing the process they began with Fata Morgana, of transforming the spaces in which they perform. As usual the shows will be highly visual and will involve stilts, though to a lesser extent than on previous occasions. Performances will be complimented by outreach work to ensure access to those in the community who will most benefit, with locals sharing the stage by participating as a chorus.

That Scarabeus should choose to step in this political direction is unsurprising. Despite this being their first issue-based performance, the company have always had an intensely political take on theatre. According to Essart this has taken place behind the scenes: ‘We are always being called the purists in circus, in the sense that we have always been uncompromising artistically. We pay a high price for that. I know that there are companies who work much more then us. But that's OK... because it's about negotiating the quality of space where you perform.’

In the past the company have found that they would be expected to arrive at a site in full costume and with full back-up. Where indoor performers would be allocated a changing room and access to toilets, Scarabeus would have to beg shops to let them use their facilities. The situation was similar with overnight accommodation. ‘As little as four years ago, in Germany we would be given private rooms with en-suite bathrooms but when we performed in Ireland we would be put in a youth hostel, sometimes sharing a room with 30 people; at the same time as an opera singer would be put in a hotel with a single room. OK there is the concept of “high art” but this is discrimination. So now we never compromise.’

The fight has also been on ‘not to produce as a factory, but when things need to happen’, and another stand has been taken over wages. ‘In indoor work there are levels of payment but outdoors it's cowboy country – really a cattle market. Many times we've talked to other companies and suggested price bands. Those are the things that we have been fighting, that have been the real political statements.’

It's logical for a company who are politicised to take this onto the stage: Arboreal is not only an ecological play, it's a product of the philosophy that drives Scarabeus. It's also a landmark for the company, taking them into new narrative and spatial realms. As Essart concludes: ‘Arboreal is the culmination of a number of things that come from our guts and from our heart. They make sense.’