A year and a half ago I sensed a big change was necessary in my work, which had been attempting to bridge the gap between the mainstream and the so-called fringe. Visual and physical theatre were finally becoming recognised as influences on establishment theatre. In a way I had nothing left to fight about.

My last production, the musical La Dolce Vita, had tried to use a populist medium to explore the theme of loss of values in our time. I had been hounded and hated by the critics, the audiences had stayed away. I was very proud and deeply compromised by the work and needed a big change. I did not want to make theatre which simply entertained. The only things to do were to fall in love or take a year off. I did both.

Lost Childhood

Then I had an idea, well really two. The first was to create a company which worked together for at least a year. I'd found it was only after this amount of time that creative ensemble work became possible. The second was to explore the world of children and childhood, or more particularly lost childhood. In my years of touring abroad I had heard extraordinary stories of children surviving the most terrible traumas through the use of their imagination. These two ideas propelled me through the next year of travelling. I went to South America and Asia. I spoke to experts, care workers, NGOs and, of course, children.

I read and observed and gradually a seed was planted that became the foundation for the project. What was originally to be a show now became a longer process; a series of pieces linked by the theme of lost children and childhood. The first two pieces would be developed by the year-long company. The first would explore, from a child's perspective, what we do to children when we abandon them. The second piece would be the inner stories of children from around the world. The final part was yet to be decided upon. I decided the company should place itself in an international context to really discover the global/archetypal nature of the work. Therefore residencies around the world with displaced children were central to the process.

I knew the work would deal with a universal subject, lost childhood. By this I meant not only children who are literally lost, abandoned or killed but also those that are lost within their homes; living in abusive or emotionally absent environments. And finally and perhaps most importantly of all, the child in all of us who has disappeared or become hidden.

Universal Language

For this I needed a universal language: mime, dance, music and storytelling. I assembled a team I was familiar with: Jamie Vartan (designer/stage manager), Jonathan Cooper (composer/musician), T.C. Howard (choreographer), Pam Vision (tour manager), and Helen Maguire (production manager). My cast would comprise Kevin Walton (Medieval Players), Danny Scheinmann (Bescht Tellers) and Sarah Sutcliffe. They were all multi-skilled and had a background in teaching or workshop leadership.

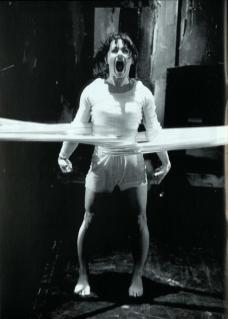

Once the company was in place I began to lay down a number of criteria that would help define the first part of the trilogy, The Hansel Gretel Machine. The piece would not use text but would be expressed through tableaux and visual action. I wanted all aspects of the work to be seen from a pre-verbal child's point of view. I had to find a language that, whilst allowing narrative development, would enable us to open up the archetypal abandonment/redemption myth of Hansel and Gretel.

I knew also that I wanted to explore the fear of loss and losing things, which are primal human emotions. We fear aloneness more than anything and will do anything to avoid or avert it. I also felt that, like fairy tales, I wanted the piece to be open-ended, interpretative rather than proscriptive. Part of my research had been in child psychology and particularly Jungian Dream Work and the Child in Dreams. I wanted to give the piece the feel of a dream. The stories in dreams often make emotional rather than narrative sense. Finally, logistically, the work had to stand on its own but at the same time be part of an, as yet, unfinished trilogy. In fact the touring of the first piece would be the process by which the second and third pieces would develop.

Lost Things & Lost Sounds

The next part of the process was to connect up with the designer and composer. I wanted the theatre language to comprise of lost things and lost sounds. I didn't really know what these were but I knew that if we surrounded ourselves with them we would immediately sense this emotion of 'lostness'. Underscoring every conversation I had was a basic insistence that because arts, children and developmental work are all marginalised and easy to push aside, I would not let financial or bureaucratic objections get in the way of the project happening. I knew if I did not say this from the start, the project would almost certainly founder.

Then we began proper. The image of the production and the trilogy was a circle. I wanted to explore the idea of a circle of people. This would be of value later when the company worked abroad and the circle would extend to include aid workers, local artists and of course children. We did class together. People sometimes think it's pretentious that I call warm-ups 'class'. It comes from my dance training, to daily re-evaluate the body, the centre and the voice. The main enemy of ensemble work is ego. Ego is always created and built on through fear. So learning about and working with fear is important.

Jamie created an environment of pictures and abstract words. The room was a horrific dump by the end of the rehearsal. I loved and hated it. It was like working in a garage. We were thrown together with pictures and objects that slowly accumulated. On the last day of rehearsal Danny said, ‘Thank God we're getting out of here.’ I felt the same but also a part of me wanted to stay.

Returning to Childhood

We restructured the room on a regular basis to try and stop formalism but I was the worst offender. Day after day I swore I'd change my working position, but I'd stay and get stuck. Jonathan spent nearly all the time in the room with us. He had chosen to work with an ewi, which is a reeded blown electronic instrument which can be given any voice through a number of gadgets and modules. He also had a keyboard and sampler. He rarely moved from his spot behind the keyboard. Accept for Jamie we failed miserably at changing our positions.

In the morning we ‘did' and in the afternoon we ‘explored' and reported back. Or, should I say, I sent the actors into different emotional territories and then asked questions. People found it hard to return intellectually to childhood but were able to re-find the big emotional states easily. I found there was a simplistic, undernourished side to their childhood memories which were dusted in nostalgia, judgement or uncertainty. Having spent time in therapy, I recognised the intellectual difficulty of journeying into the land of childhood. Yet when it came to the emotional/physical work there was no such resistance. Jonathan called the talking banal and hated it and yet he would immediately write music wholly connected to the emotions involved. I asked him about this process and he could not answer how it happened. This side of the work intrigued and bothered me. I felt that the quality of discussion between us was being eroded.

Dreams & Myths

I slowly began to see something emerging. It often dwelt in the periphery of the work: it was a descent into the archetypal realm which is the state of pre-verbal childhood, the time before we make sense of things and experience almost exclusively through our senses. We stepped increasingly into a the world of dreams and myth.

Early on the company read Hansel and Gretel then stuck the story onto the set. I think it helped us feel secure. We all knew it was only a stepping off point. I found the story annoying and limiting. During the time of research I realised how Victorian the whole notion of childhood is. Now I realised why I was having difficulty with the discussions and why I was irritated by the story. Victorian values simply see childhood as an idyllic waiting station before the main event of adulthood. Everything I'd seen, read and experienced in the past months contradicted this. Childhood is not the problem, it was our notion of adulthood. A better model seemed to be that as adults we are children who have developed very large bodies.

When I began to apply this to the process of work things began to spark.

I slowly placed the centre of the story on Gretel, giving her a birth and early life prologue. We explored the world of abandonment, the sense of total despair at the death of her mother. This emotion lay at the heart of the piece. The emotional world for a child is everything, it is totally linked to their physicality, to their sense of self. Gretel's hair became an important symbol as did the bird that reoccurs throughout the story. I tried not to over-define these symbols. Our resident Psychotherapist Alaine Krimm would occasionally comment on their nature and power. Thankfully as the work developed we had no need for language. It was a world of images and pure gestures. A Noh-like play began to appear. A heightened melodramatic/mimetic style that seemed to emerge naturally.

Sleepless Nights

I began to direct and structure short tableaux and vignettes without necessarily knowing how they would fit together. Character was touched on but left. Deep inside I knew I was waiting for the story to reveal itself and gradually it did. I kept saying that, like dreams, we must not stare directly at the work but like particles of dust on the eye, let the material float by of its own accord. When this happened I was really happy. When it didn't I'd have sleepless nights. I had absolutely no idea if it all meant anything, it was exciting and frightening. However, I felt we were on the right lines.

Meanwhile Jamie was looking at objects and textures and possibilities. He was drawing scenes and storyboards. His designs all came out of the process of watching the performers work. The room was getting messier and darker. Light bulbs kept blowing, people were getting ill. Jonathan kept having migraines and I seemed to see less and less in front of me.

Two weeks before we opened I was at a drinks party for the opening of the London International Mime Festival. Suddenly I was surrounded by friends and colleagues. I felt an overwhelming sense of failure and futility. I had recently turned forty and thought I really know nothing. The programme for the festival smacked of innovation, success and vitality. I thought of my dingy garage as a nightmare. I thought of the unbelievable trouble I was getting everyone into. That night my partner Val came down with a double kidney infection that gave her a rocketing temperature and I dreamt of my body decomposing. There were only two weeks left to go before our first night.