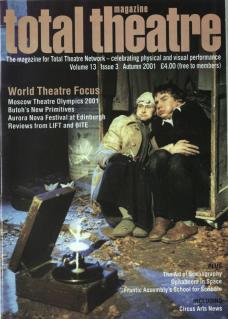

Gekidan Kaitasha are one of the most pioneering and provocative ensembles in Japan today. They are currently conducting a world tour including the UK as part of the Japan 2001 Festival. The work they will be performing is called Bye-Bye: The New Primitive, Kaitasha's culminating stage production of the 1990s, dealing with the physical and political aspects of the human body. The work consists of scenes that were reconstructed to document how that decade fell into functional and political disorder. It is a work that has seen several manifestations, a work that has evolved and will continue to evolve.

Gekidan Kaitasha, which means the 'Theatre of Deconstruction', was founded in 1985, inspired by Noh theatre, the philosophy of Tatsumi Hijikata (the pioneer of Butoh), Pina Bausch and Martha Graham. Kaitasha's work is influenced by the atmosphere of each venue in which the performance takes place. The company began working in environmental locations, including city ruins, streets, parks, train stations and riverbanks. Their narratives are composed primarily of physical movement and expression, sound and rhythm rather than words. Language – mostly English and consisting of single phrases or words – is used sparsely.

The company has from its origins experimented with object installations, electronic music, film and other visual media. These works are highly emotionally charged, and some of the images they create are profoundly disturbing. Their characteristic repetitive, obsessive movements are brimming with ferocity imbued with violence.

As mentioned before, the company has been influenced by Tatsumi Hijikata. The term Hijikata coined – Ankoku Butoh: the dance of darkness – is an apt description of Kaitasha's work. Ankoku Butoh, founded by Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, was a revolutionary underground art movement in the Japan of the 1950s, profoundly influenced by German expressionism and the work of Antonin Artaud. Other seminal influences included Arthur Rimbaud and Jean Genet and Japanese artists such as Yukio Mishima.

Hijikata's first work, Forbidden Colours, inspired by Mishima's work of the same name, in one blow reinvented Japanese contemporary dance-theatre, which had previously slavishly drawn on western forms. Such a process had been impacting on Japanese art primarily since the Meiji Restoration. The revolutionary experimentation taking place in the art world was inextricably linked to the socio-political situation of Japan in the post-second world war period. Although influenced by a number of European artists, the body that Hijikata was searching for was a Japanese body. Ankoku Butoh is not easy to comprehensively define because it is in a process of inherently redefining itself, but here I outline some general observations.

The body is the site for exploration

The body that Hijikata looked for was a Japanese body and the bodies that became his muses were marginal bodies in Japanese society. Kayo Mikami writes: 'Butoh is now, always now.' For Hijikata his own body was the site for such a journey. Hijikata's choreographies for his dancers began with words that he would throw at them from which they would have to improvise. Words were important to him. As Sondra Horton Fraleigh describes in her book Dancing into Darkness, instead of liberating the body from language, Hijikata tied the body up with words, turning it into a material object, an object that is like a corpse. Paradoxically, by this method, Hijikata moved beyond words and presented something only a live body can express. That is the essence of Hijikata's Butoh. Hijikata saw human existence as inextricably part of the body. But this body only comes alive when it is chased into a corner by words and pain – that is, consciousness. He rigorously practised this point of view with his own body and life.

The rejection of existing Japanese vocabularies of movement

A move away from forms such as Noh and Kabuki towards influence by more primitive expression inspired by shamanistic practice and Japanese culturo-aesthetics relating to nature. This is not to say Noh or Kabuki has not been influential for individual artists but this refers specifically to the overall vocabulary of movement.

A harmonisation of male-female energies yang and yin

This in both male and female artists.

The creation of highly personal dances

Kazuo Ohno in particular elucidates ‘finding one's own dance'. There is a correspondence in Pina Bausch's thinking: 'I am not interested in how the body moves but what moves the body.'

The relationship of the body to the universe

Kazuo Ohno discusses this and refers to this always. In a workshop that Fraleigh undertook with him he gave her an improvisation exercise, describing it as follows: ‘Tonight we start in the mother's womb. We are swimming in her waters and drinking her life. When you move you should touch something, hear your mother, touch her. Keep this in mind – your body is your mother. She is feeding you the universe as it exists in everything, even so small a creature as a moth. The form of the universe imprints a moth wing. The mother contains the universe, she makes a soup of the universe to feed her baby, a soup of the moth's wing. There are parallels here in the work of Isadora Duncan. In her biography she wrote: ‘I was seeking and finally discovered the central spring of all movement, the crater of motor power, the unity from which all diversities of movement are born.'

As a spectator, I perceive some correspondence in the body expression – shintai – of Gekidan Kaitasha. How could it not be so? However, their body work is not a mirror image of Hijikata's work. It is director Shimizu's distillation of Hijikata's philosophy that is most interesting. Hijikata regarded the brain not as a distinct or primordial entity but as an organ only, one part of the totality of the body and one part of the body's 'creative' experience in performance. An old Chinese saying, also known in Japan, says: ‘Think with your abdomen.' (The abdomen here represents the totality of the human body.)

In a recent conversation, I asked Shinshin Shimizu, artistic director of Gekidan Kaitasha, to explain his approach to shintai. He describes below an exercise in walking:

‘This is a pretty basic thing, but we have done Hakobi (carrying) – that is, walking. However, it is not 'walking', actually. It is not a movement of the foot. Normally, someone who starts walking moves his leg. But I set up Ki (soul) in front of him. Ki comes from his inside, his mind... He chases the ki so that he carries his body ahead. This is the thought of Hakobi. So, he is not walking, but it can be said that he is chasing his representation, his shadow...'

Shimizu develops this explanation of process further: 'I think that it is necessary to carry out another process with the body that is called "remained as it was born"... If somebody thinks that he can use his body freely, he does not play as an actor. Somebody who feels something strange and unnatural against his body, exposes his body on a stage. If I express it in language, I use ki, Kage (shadow) and the Noh sense of Hana (flower) – a body left behind... Regardless of East and West, everybody seeks freedom on the stage. I am not setting a trend of the new era, but am in this stream of history.’

Shimizu and his company acknowledge the influence of Hijikata but have a contemporary interpretation of Butoh that investigates the notion of Shinkei (nerve or neuron):

'In the sixties, what Hijikata was concerned with was the physical body, not nerve. The body, in this sense, has already become invalid... there is a (nerve) memory of the past in the performer's body... If someone says "memory", it is a history...'

Gekidan Kaitasha are transformers of history – the history of Butoh, of other performance forms, of collective Japanese experience and of the experience of individual bodies.

The company will be performing at the ICA in London at the end of October and then touring. For full details email theatre@celtic.co.uk This article includes an extract of an ongoing discussion between artist Ajaykumar and Shinjin Shimizu, artistic director of Gekidan Kaitasha. An extended version will be published shortly in the web journal at: www.dramforum.net