Have you always had a passion for theatre?

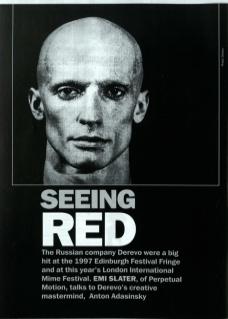

I have a very bad memory. It's not just that I don't remember what happened to me a long time ago, I don't remember things that happened a few days ago. So I can't remember whether I have always been interested in theatre. I used to be more interested in photography: walking around with a camera and long hair. On one occasion I was making a photo reportage of a group of actors for a newspaper and the oldest member of the group asked me for my contact number. That man was the Russian clown Slava Polunin. He said, ‘I have a theatre school, you can come and join if you want.’

Was it really that easy?

Well, after some preparation, I auditioned for Polunin's clown school. He liked what I did and took me into Litsedei, his clown company. The group was already quite big, with seven people. I spent four years there. The clowns were all happy and I was the sad one. We made a performance called Dreams, half based on Slava's ideas and half on my own. Slava and I had very different ways of thinking creatively. I found the ideas at Litsedei too concrete, so I left. For half a year I relaxed and didn't do much. I opened a cafe for three months, I played my trumpet. Then I realised I needed to go back to theatre again. So I held some auditions to start my own company and about fifty people came.

Fifty people came, just like that?

Yes, I was already very famous! And I opened a studio and started a new group and a new show with new ideas. People came every day and worked very hard. It was free. No money changed hands.

How did you survive financially?

I was working in the Palace of Youth, St Petersburg, in the cafe and I did pantomime for children. We worked very hard for many hours a day. People started to leave because it was too hard and after one year I had only six people left. This group became Derevo.

Then the Rock group Avia asked me to make a show with them. It was incredibly successful, because no one in Russia was making shows like it at that time: with mini skirts, blond girls, acrobatics, dancing, human pyramids. It was a bit like agit prop from the 1920s and 30s. But I decided I should concentrate on my own theatre work instead.

Have you ever had formal training?

No. I just made it up as I went along from books. There were a lot of talented people around me, so I learnt from them. I did workshops, I worked in dance and in pantomime but I never formally studied theatre. My main inspiration was a documentary book of old photographs of schizophrenic people. I opened the book and the power of the pictures just sort of jumped out at me because of the eyes of the people in them, they went right through the camera. It shocked me. So I said to my performers, ‘I need these eyes. Can you play these eyes?’ I could feel the power so strongly. But of course nobody could do it. There was a kind of aura, a kind of energy surrounding the pictures in that book. To find it in real life was very difficult.

Then after about two or three months I found a book about the Butoh dancer Takuki Tigitata who studied the technique of Katsuo Ono. When I opened the book I discovered the same power and energy, the same eyes, and I saw that the same strange aura existed in Butoh. I know Takuki Tigitata isn't schizophrenic, but he has the same energy. He is an incredible dancer and I saw from his work that it is possible to make work with the kind of energy I found in my book of schizophrenic people.

We started doing lots of exercises, which mainly started from the idea of being in the ‘zero’ position. This is a neutral position, not like neutral mask, but a position that makes the idea of neutrality strong. We invited our friends and we played around. We made actions, happenings and dances outside in the street. These things were unheard of in Russia at that time. It was strange the way people reacted when they saw naked people. If you were working really hard then it was seen to be okay, but if not then people just wanted to kill you.

Naked bodies out in the snow in Russia?

Yes, I trained the company very hard. In the 90s people started to come to Russia with Perestroika, this opened the door for us all. All the producers were coming to Russia looking for new ideas, new hope for the world and lots of people came to see Derevo.

How did you manage to get your own space?

You could get anything if you really wanted it. We got a place in the Palace of Youth with a stage 10m x 10m, sound and light. It was really unbelievable. Of course it was soon over but for a while it was incredible. We didn't pay anything, not one penny. And the ticket prices were split between the Palace and Derevo and that was the beginning of us starting to have money to survive as a theatre company.

Which pieces did you perform?

Grey Zone, Red Zone, Brown Zone, Blue Zone or Performance Number 1, Performance Number 9 or Performance Number 4 and so on. Something different every night. For one performance we took a whole load of photographs from our past and just stuck them in a fire: the real Russian underground burning their past! It was hot and there was a strong smell coming from the old photographs and at one moment one of the performers, Dima, started to dance with a table. We worked on the river sometimes. We used rafts and it looked as if we were walking on water! There were five embryos floating down the river. It was the anniversary of Hiroshima and Japanese television asked us to make an action.

We also worked with masks in the snow. We put chairs in the middle of Nevsky Prospect and made moulds of people's faces. It took fifteen or twenty minutes and we played accordion and drums. The look on people's faces when we took the plaster off was incredible, because under the mask all sound and vision had changed so when it came to taking it off they had an incredible experience when they opened their eyes. People shouted and cried, etc. They literally screamed about what a strange experience it was.

We only did one thing in Moscow (Moscow is the political capital of Russia but St. Petersburg is the cultural!), when we tied ropes all around and across the stairway of a really traditional drama theatre in Moscow. I wasn't sure how strong the rope would be, but we jumped from the top of the stairway into the mesh.

When did you leave Russia?

Eventually normal life came to Russia. People started to think about rent, business and money and we realised we had done a lot there and it was time to leave. We had a good contact in Prague who invited us to work in a real theatre so we moved. It was time to move. We have lived in Amsterdam and in Florence. Now we are in Dresden in Germany and that is very interesting because the German people really want to understand what theatre is all about. It is not just a game for them. It is very interesting to work where people are so serious about performance.

Do you have your own theatre?

We are thinking about setting up our own theatre and starting up a school there. I think it is very important to have long-term training – not just to leave people adrift after a workshop but to give them the opportunity to actually perform.