The boat was big but the sea was much, much bigger / The sea changes all the time / The sea is like a desert / You cannot live in the sea / You visit the sea / There is much more water in the sea than on the land / People do not come from the sea (this may not be true) / The sea is alive / The sea can consume you / If you fall off the boat you will die / The boat is like a prison / There is less to see on the sea

I am stuck, stuck in Nuremberg. Everyday I borrow a bike from a German friend and make the 40-minute ride out to the airport to get my ticket re-booked for the next day (Icelandic volcano willing). At least the weather is good and I have friends to stay with. The airport is very quiet; the Lufthansa ladies are polite and apologetic, a little bewildered and not very helpful.

Life runs so fast, I have meetings that I cannot make, stuff to cancel and re-arrange. I am impatient. I hate to wait.

In November of 2009 I went on a boat, a big boat, out into the big ocean. I did not go on my own: I went with a Dane, two Norwegians, a Belgian, two English, and a Czech. I went with a musical director, six actors and a production manager. I went with a folder of letters from an Icelandic writer and a suitcase of mysteries from a Danish set designer. We all went on journey, from Le Havre in France over the salty sea to the French West Indies, across the Atlantic. We left Le Havre in heavy seas and high winds from the tail end of an Atlantic storm. None of us had any idea what to expect, or what we would find.

It was a cargo ship and it carried 5,000 containers bound for the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique. The crew could not tell us what was in the containers, as they are not allowed to know. They bring back bananas, sugar and rum from the West Indies. They were quite suspicious of us arriving with our instruments and looking like a strange collection of misfits. We got onto the ship, took our bags to our cabins and waited, and then nothing happened for quite a long time.

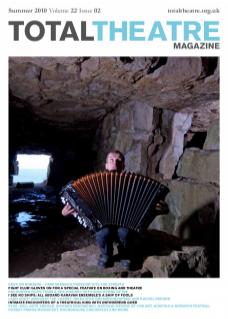

The Fort St Louis run by the French shipping firm CMA-CGM was to be the location for the first phase of research and development of our new show, Tales From a Sea Journey. Eight of us made the trip and two others contributed to the process even though they could not be on board. As the title suggests, the show will be about stories from the sea, about songs from the sea, and about the pull and power of the sea. But it all started long before the boat…

In 2007 we took part in China Plate and the Arvon Foundation’s fantastic Dark Room project that teamed us up with a writer to work for a week at John Osborne’s former country home, The Hurst, in Shropshire. One of the strongest experiences of the week was the sense of isolation and focus that the location brought. There was almost nothing for miles around, and we had no signal on our phones and limited access to email. In the past we had often sought out isolated, detached places as the location for our first work on a project, a desire that goes right back to our first work together as a company in the small Czech village Mseno. The company really started as a small group of friends going to a kind of isolated retreat to try to start some work together. It was after that week at The Hurst that we started to talk about a boat, and then to find out how and where it was possible to travel. We also started to talk about working with a writer on a show, and working with a mixture of true and made-up material. These would be new steps for us, new ways of working.

In the past we have always started with narrative, using a basic story as the beginning point for improvisations and ideas. In general, these have been true stories rather than literary adaptations or our own inventions. We have also always started with music, with learning and playing music together – it has always been a principle for us that a New International Encounter (NIE) show should be presented by a group of actors who are also a band on stage together. Starting from the base of an experience that we would share together meant that we needed a broader way to come to the material, so that we would become a part of the material – the subject matter as well as the means of expression. I didn’t really know what to do, so I decided that the best strategy was to get other people to do things instead – I asked each of the people involved to bring three stories and three songs from the sea.

Meanwhile Kjell Moberg, NIE’s Norwegian associate director, had been in contact with an interesting Icelandic writer called Sjon who had written songs and poems as well as some short novels and theatre pieces, so it seemed like a good fit to work with him. Sjon could not go on the boat but he sent each of us a letter with instructions and provocations, but more of these later…

As ever at the start of an NIE project there was an initial stage of arrivals – arrivals by plane and train in Paris from London and Oslo, from Prague, Copenhagen and Hamburg. Then arriving by train to Le Havre late in the night, and arriving in a small hotel, and then a bar. It always takes a long time to start, and I am impatient, I hate to wait.

Boarding a cargo ship is not like boarding a plane. Cargo ships run to a schedule created by container port authorities and set by sea tides and pilot boats – and in our case by striking French dockworkers. We waited in Le Havre for three days before finally leaving the harbour, out into big waves and a gale in the Channel. We made a brief stop in Brittany and then headed out towards the Azores and the Caribbean.

The experience of being on the boat was complex. It was a great space for the imagination, but also quite boring at times. The weather was bad at the start so that many of us were sick, or at least not able to do much work. It was beautiful but also like a prison – there was no way off. It felt dangerous but was also quite mundane.

Once the weather settled down a little and our own excitement abated we began the work. We took turns to tell stories, sometimes as small performances that happened in different parts of the boat. We opened the letters from Sjon the writer (it was like Christmas!). Each one contained a message that was a provocation to a narrative: a postcard from Iceland asking for help to find a family lost at sea; a letter from a father to his son wishing him luck on his trip and enclosing his lucky 100 Yen bill.

These were all very inspiring and each came to form the basis of a solo performance that was delivered as part of our work on the boat.

We opened the suitcase that Marie our set designer had sent. She had also given us tasks to carry out. We each got a disposable camera and secret instructions for a set of pictures that we should take. There were also costumes and object to use. The aim of all of this was to find ways to explore our situation and subject. The stories that each of us brought were hugely different: some were historical and true, others were myths of the sea. Some were urban myths passed on and embellished onboard. I brought three stories of shipwrecks, ending with the wreck of a mail ship in the Caribbean where all passengers drowned, tied into their beds by the crew who wanted to keep them safe in a heaving storm.

We spent loads of time playing music, at first in the passengers’ common room until the cook complained to the captain. Then outdeck where you have to play loud to hear yourself over the wind and the sound of the engine. As the weather improved we were able to visit the front of the boat – the Leonardo and Kate in Titanic bit. This was a revelation and became our favourite place onboard. It was quiet away from the engine noise of the stern, you could see flying fish jumping out of the way, and you could sit on a small platform and hand your feet over to the Atlantic fifteen metres below as we crashed through the waves. Once we passed the Azores the weather improved, and the clear sky at night, with no light pollution from the land, was amazing.

At the end of the journey we have hundreds of photographs, twelve recorded songs, fourteen stories that we all thought might develop further, the short performances made in response to Sjon’s letters – and an amazing experience. This becomes a bag of material to mix together, so that when we improvise and start to shape a show we have them available to offer immediately to the process.

We came back by plane via Paris – we travelled ten days by sea and then back again in ten hours. The journey in the air is, in many ways, more remarkable and miraculous than the journey over the sea, but it is much smaller journey for the imagination.

I will rehearse the show some more if I ever get back…

For further information on touring plans for Tales From a Sea Journey and other NIE shows, see www.nie-theatre.com