I make work as Emma Rice, not as ‘a woman’. Nicholas Hytner’s intervention [in support of Kneehigh, accusing critics who had slated A Matter of Life and Death of misogyny] was valiant but took the debate into territory I’d never planned to enter.

I feel very strongly that the biggest block to anything creative is fear. Everyone is frightened, and it is a useless emotion. As a director, I do as much as I can to remove fear from the process, to make it easy, and to protect people from the bits that aren’t. They do the most scary part – getting up on stage in front of people – so I do feel it is my job to shoulder a lot of the rest.

I don’t like fighting and I’m no good at it. I lose fights. I’m much better at manipulating!

I am passionate about the collective imagination. I think that if I give people enough information about the world of the play, if I do my job properly at the beginning of the process, then the collective imagination will become much, much stronger than anything I could come up with on my own… you get this wonderful moment when someone says ‘I know this might sound stupid, but….’ and suggests something completely brilliant.

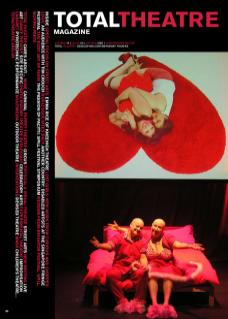

There are key creative decisions which I make at the beginning of the process as author, not as writer, but as author. So, going back to The Red Shoes, I said, ‘This is going to be told by a chorus of people with shaved heads, who have seen things they shouldn’t have seen.’ Originally it was a chorus of the cowards of the First World War. And I knew that the storyteller would be a transvestite, someone who had embraced their red shoes. So none of this was up for debate. I don’t want to be part of a co-operative, and having been an actor, I don’t think that’s what actors want.

Casting is the hardest thing. I’m not looking for the greatest actors, but the right people, who may also be the greatest actors. I like people who are interested in the world, who are looking out at the world, instead of in at themselves. I like naughty people. I look for that twinkle.

For us, the story is key; that is the map. Most theatre is text-based, and your job is to interpret the text. The text is the map, and without it people feel lost.

We had two weeks Research and Development for A Matter of Life and Death, two years ago. It was very useful, and I felt that we could have gone into rehearsals then. But the National – who of course have to do this – said ‘now we need to see a script’ and I said ‘I don’t do scripts’ and they said ‘we completely understand, but where’s the script?’. With the National, it’s like being invited into someone’s house, and at some point, you accept the rules of that house.

When the reviews came out, what did hurt was that the design wasn’t mentioned, the music wasn’t mentioned. I’ve been working with Bill (Mitchell) for 13 years, and this did feel like a magic moment. This design wasn’t born out of sweat; it came as a result of two people who totally understood each other. The task to fill the Olivier is huge; there’s no point doing Poor Theatre on the Olivier. Though we did start with a completely bare stage, and strip it right back to the back wall at one point, so there are still elements of poor theatre in there.

I love the Olivier amphitheatre – though I would prefer it to be a single rather than a split-level – Kneehigh’s background is outdoor, amphitheatres, quarries. So we weren’t scared of it. We can bellow like bastards, but it is a tricky acoustic.

This was the first time I had worked with a choreographer [Debra Batton], and it was brilliant, but not easy. Because I’m very clear about what I want, there’s not always a lot of room. I know what I want and I’m absolutely clear in what I dream of. But she was brilliant, with the rope work, lifts. I think we would work well next time on another, more movement-based project.

I find that stories reveal themselves to you when they’re important. Why did I wake up one day and think ‘The Bacchae’? I have never had an urge to create an original story. Partly because I love to bounce off what is there, what is traditional.

Ten years ago I never thought I would direct. Maybe this is where gender politics does come in. The girl in me never believed I would be the leader. And I’m very glad I was in my 30s before I started directing, because then I realised: one, I have something to say, and two, I can say it.

I’m still very romantic. I believe in love and I believe it can be destructive. And there’s the other side, which is about being bad, which I have explored in Lulu and The Bacchae. Love, and being bad.

There are gatekeepers, I think, who decide what theatre should be, and perhaps don’t recognise that it is a fluid artform. For many conceptual artists, theatre is a dirty word, all about pretence and lying. And I say ‘come and see a Kneehigh show, that’s not what we’re about’.

There are powerful people who feel that the well-written play, and the well-spoken word, is in danger of dying out. And they may not be wrong. But this becomes a block to seeing the possibility that what replaces might be beautiful, meaningful.

On one level, being at the National, at the heart of the establishment, is really simple and it’s great. It is recognition, and your mum and dad can come and see you and everything. On another level, it doesn’t feel quite like home. But that brings up lots of interesting questions, about ‘what is home?’.

The work isn’t just what people see on stage. I joined the company 14 years ago and fell in love with the place, the people and the work. Its more than just a collective, because we are experiencing life with one another; marriage, divorce, birth and death. And that is deeply moving.

The main Kneehigh project now is this touring tent called The Asylum. In its smallest incarnation it could go up on a school playing field, or its largest sit on Sydney Harbour. This is the future, for Kneehigh. Because we do need to face that challenge, how to maintain our character? How does a company like Kneehigh continue? Not to start playing by other people’s rules.

Kneehigh comes from a very democratic background. And we want to be able to get a 15-year-old off the street and for them to enjoy the performance. Ask people in Cornwall ‘do you go to the theatre?’ and they say ‘no’. Ask them ‘do you see Kneehigh?’ and they say ‘yes’.

I’m a bawdy, not an intellectual. The work is bodily. It is about fighting, farting, loving and fucking. So the tent is called The Asylum. It’s the perfect name. It’s about madness and shelter.

Cassie Werber interviewed Emma Rice at the national Theatre, 19 June 2007, during the run of A Matter of Life and Death. See www.kneehigh.co.uk