How to review?

As a theatre practitioner, I believe developing a handle on how to describe your own work and the work of others is important. It’s an empowering way to self-define, allowing you to frame the agenda in those discussions that necessarily surround what you have made. It hones your analytical skills by encouraging specificity and thoughtfulness in your responses. It develops relationships and connections between others’ work and your own, an ongoing mapping process in an ever-shifting landscape. In short, I think it’s too important to be left to professional critics. In the field (or perhaps multi-verse) of ‘total theatre’, practitioners’ interest in subverting, expanding or reclaiming formal territories makes the role of those written framings that mediate work’s reception through reviews, blogs and marketing material more powerful. Sharing these views, the Performing Arts Network Kent (PANeK) teamed up with Total Theatre Magazine for the Writing Performance project that sought to empower participant theatre practitioners, teachers and arts managers better to describe their own and others’ work.

The project ran alongside the theatre/multiarts programme of Canterbury Festival. Participants all saw and wrote about three performances from a programme of five selected by the facilitators (members of Total Theatre Magazine’s editorial team), receiving individual feedback on each written piece which was produced in response to one of a menu of potential journalistic briefs. This process was bookended by two extended seminars that investigated the practice and theory of critical writing.

The initial seminar set out to frame the exploration by investigating what makes a good review an effective record and comment on the experience of a show. Notions of evocative communication, accessible commentary and the translation into words of work operating through a variety of other forms were discussed. One of the key ideas underpinning the project was the sense that established critical models are biased toward the literary: privileging content and style over form and thereby problematic when applied to models that challenge this hierarchy. In this first session we looked at one of Kenneth Tynan’s reviews of the Berliner Ensemble as an example of a more classical approach to writing on performance.

For all of its lofty erudition, this writing surprised and inspired me with its cultural breadth of reference and witty, lyric verbal grapplings with performance languages. His writing challenged my assumption that traditional literary criticism was anathemic to non-literary forms and reminded me how rarely I saw great reviews for more formally experimental work that treat the content with as much respect as its vehicle.

The challenge set for our writers was to develop their processes of using written critical responses to expressively articulate the nature of new work and their opinion of it. The festival context proposed a particular emphasis as a programme of theatre with a relatively broad appeal but with selected shows that drew from a range of forms including cabaret, physical theatre, live music, puppetry, and devised work. Each theatre visit was accompanied by a member of Total Theatre Magazine’s editorial team allowing us to offer close feedback on both the journalistic form and content of the reviews during this central phase of the project. Each participant received both written editorial comment on their writing plus a one-on-one tutorial session to discuss the comments and their responses in more detail.

The final workshop session gave us a chance to discuss the work seen together (we asked participants not to discuss the shows with each other whilst they were still developing their writing) whilst starting, tentatively, to define some of the formal qualities of an effective piece of critical writing (one key initial question – effective for whom?). Troubleshooting issues thrown up by the experience of writing for the project brought up some interesting questions – from the practical (‘how do you write and watch at the same time?’) to the philosophical (‘how do you create a good ending?’).

As you will see in the material following, every participant wrote a review of Forkbeard Fantasy’s new show The Colour of Nonsense and their responses excavate some common ground as well as illustrating fascinating divergences in response. We explored in the project the parallel responses of the critical (or perhaps artistic) analysis of whether a show is successful within its own terms vs. the subjective reaction to elements that you enjoy or not. The opportunity to explore multiple reviews of a single show really illustrated for me the dynamism of this model and is a process that feels of particular relevance to work seeking to challenge performance conventions.

The Reviews

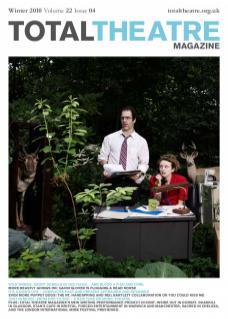

The first five minutes set the tone gleefully: a middle-aged man (played by Chris Britton) arrives at his office; the rain, his slog up flights of stairs, the oddball characters he passes along the way, are all conjured via Foley sound performed live on stage (by Ed Jobling) on a baroque sound desk. The world is madcap and the message clear – a complete, artificial reality can be conjured through art. The man, we learn, is a conceptual artist whose current commission –‘Nonsense’ – is proving slippery. This frame offers us a doorway into some of the show’s most tenderly treated material: verse and animations (by Tim Britton) based on Edward Lear’s poems and philosophic riffs on the nature of art.

But the world of our three artists – Splash, Line and Scuro – delves deeper in its exploration. Forkbeard’s trademark collision of live action with filmed frames and animations, which effortlessly and hilariously pepper the performance, foregrounds the mobility of illusion and reality in the theatre. In a show whose material seems made for Forkbeard, The Colour of Nonsense starts to dismantle the idea of art, and illusion, itself, as the trio embark on a commission to make an invisible artwork. Whilst obviously drawing from the Emperor’s New Clothes, their treatment goes further in its satire and its final ambiguous gesture that the illusion is both fantasy and real. For what else is theatre if not the illusion simultaneously real and imagined?

These rich and involving ideas are ingenuously packaged in a colourful melee of visual and comedic storytelling. Preposterous masks, cartoon, live animation, the warm charm of thirty year’s of collaboration, some very silly characters, and one very clever parrot puppet vent – the show can occasionally feel over-packed but certainly offers a wild and exhilarating ride with a company for whom fantasy is a trademark.

Beccy Smith is a freelance dramaturg, director of Touched Theatre, and Total Theatre Magazine Reviews Editor

Trepidation mixed with excitement is the best way to describe my feelings when entering the Theatre Royal Margate for Forkbeard Fantasy’s The Colour of Nonsense. Suppose I don’t get it? Suppose it’s too highbrow? Suppose everyone is laughing – or worse, crying! – and I just join in without knowing why! Suppose there is just that one little bit of me – a fly in the ointment if you like – that says, ‘But who is to say whether this is funny, sad, relevant?’ Hooray for that fly – ‘Cedric’ – star of The Colour of Nonsense, and the valued pet of Line, Scuro and Splash, conceptual artists of some renown (twenty years ago), now facing a looming deadline for a Milanese exhibition that they haven’t even started work on. When Hermione, their agent, abandons the three and gives the exhibition instead to a delighted young Turk snapping at their heels, they are left with their exquisite tulip miniatures, hysterical comic book, and the comic musings of a pantomime parrot. Enter the sinister Angstrom with a commission so provocative they cannot resist...

With a sigh of relief, here is the acknowledgement that contemporary art can have us wondering if we are in some way being duped. This is a breath of fresh air from all that theatre that takes theatre so seriously. The Colour of Nonsense owes much to Hans Christian Andersen for the basic premise and yet manages to be powerfully moving, particularly with the delightful animated rendition of the Edward Lear poem, ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’.

Mandy Hare is the Theatre and Events Manager at the Hazlitt Arts Centre in Maidstone

Set in the studio of the cartoon-like characters of Line, Splash and Scuro, The Colour of Nonsense begins with three artists at work creating an installation called ‘Nonsense’ for a big exhibition. Line leads the narrative as the creator of a secret comic book detailing the everyday lives of the studio. Splash fell from the top of the art pile ten, no twenty, years ago and wears the wig, shades and suit of a 1950s game show host or vaudeville entertainer. Scuro, 50% performer, 50% technician, skulks in the shadows lost in his world of sound. Chris and Tim Britton in particular are wonderfully entertaining performers, their age and background (they’ve worked together for over 30 years and aren’t professionally trained actors) enhance their presence.

The Forkbeard multimedia trademark of performers controlling the sound, projections and puppets on stage creates an inclusive live experience. Playing multiple roles the cast introduce other characters including the villain Angstrom and the Stanley Baxteresque Hermione. These characters showcase Forkbeard’s use of technology and theatrical gags (Hermione only appears on a screen which represents an elevator), but there were a few too many characters, individual stories and themes going on without the opportunity to explore, understand and absorb each one.

Amongst the absurdity of Cedric the talking fly, tulipomaniacs and invisible artwork, lies an understanding of the human condition. A charming illustrative animation of the Edward Lear poem ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’ catches you quite off guard, provoking within me a genuine emotional response. As Line says: ‘It’s a truly wondrous thing to be always searching for something you really love but will never attain.’

Natalie Eacersall is a professional actress with writing, devising and directing experience, and an MA in Theatre Practices from Rose Bruford College

The delight in The Colour of Nonsense is how it skilfully persuades us to abandon ourselves to its nonsensical world and remain there. In this, the piece’s key influence could not be clearer: the irreverent tone of Edward Lear’s poetry pervades throughout. Indeed, through this lens The Colour of Nonsense revels in a heightened sense of the ridiculous to better reflect the absurdity inherent in striving for order in the first place.

Events spiral out of control at a farcical pace as the artists Splash, Line and Scuro struggle to generate material for a ‘Nonsense’ exhibition. Amidst the chaos, the ultimate Invisible Artwork is born, lauded as the epitome of conceptual art and sure to save the trio’s fortunes, representing, as it does, absolutely nothing. Inventively realised, with effective inter-textual references including The Emperor’s New Clothes, the exaggerated characters intrigue us, and drive the narrative well for the most part, only occasionally lapsing into a pantomime style that grates a little.

Forkbeard Fantasy have a long-established reputation for inventive multimedia theatre, and this production utilises imaginative effects to create engaging narratives examining society’s thirst for something ‘new’: Line disappears from stage to follow Lear’s animated Dong, climbing a filmic ‘abstract staircase’ which is beautifully executed, and characters on screens pass actors objects which quickly become real. Here boundaries between recorded and live action and reality and fantasy are gleefully blurred until one happily ignores the joins. Yet what appeals most is the robust storytelling, and the sheer creative energy that it is its result.

Sarah Davies is a drama lecturer, playwright and director based in Kent, with specialisms in Contemporary Theatre and Scriptwriting

The Earth has flooded and humans live in tower blocks in the North Pole. Plant life is reduced to treasured collections and only jellyfish are left in the sea (made into chewy sandwiches!). In this dismal future live conceptual artists Splash, Line and Scuro, who are preparing an art exhibition titled Nonsense. The stage is set as a cluttered, top-floor studio, ideal for pantomime entrances through imaginary windows, exits up temporary stairs and the baddie falling down a lift shaft, somewhere off-stage-left.

The Colour of Nonsense took three worlds and jumbled them up into one stream of slapstick, anarchic action. Us in the theatre, the North Pole future and the past through Edward Lear’s evocative poetry and illustrations, woven together in a bubble of rare innocence. Forkbeard Fantasy’s comedy theatre was devoid of all smutty, lurid or demeaning jokes. However, with too much going on, the allusion to our human indecision to react to the environmental collapse heading our way was lost in the pursuit of a quick laugh. Sitting on red velvet, in a spectacular Georgian Theatre, my mind wandered to Margate Theatre Royal’s past and to those who had shared the stage with the three men in daft costumes, now fooling around up there. Perhaps that was it! To realise the nonsense of sitting in a theatre when the sea, just down the road, is slowly rising.

Alice Taylor is a drama and arts educationalist working across the South East

The Colour of Nonsense tackled theatre from an angle I hadn’t personally experienced before. The play was crammed full of intelligent observations and insights on human and social behaviour, and packaged colourfully in theatrical nonsense! The play uses film, animation, and a collection of props – techniques which at times seemed to have moulded the development of the script rather than to have been created in service of it. Nonetheless, one couldn’t help getting the strong sense that there was a collaborative familiarity that allowed the performers to be somewhat less attached to their strange onstage props and technical goings-on than a less experienced performance group would have been. There was also the sense that this was a performance that had grown from the performers’ own understanding of what they personally found amusing rather than a direct desire to please the audience, and this gave a kind of childlike innocence to the overall performance which was at the same time in no way childish.

This maturity of the actors and their obvious cohesion allowed them to focus on the intricacies of the production and the well-developed storyline and script. The script was made up of a number of astute observations on human behaviour that were beautifully concealed in a combination of poetry, rhyme, animation and sheer nonsense! The overall effect was delightful and one felt fully immersed in the perceptions of the individuals engaged in the performance while at the same time kept at bay by their own evident confidence in their art.

Lorraine Iwa Kashdan is a poet, a performer, the director of The Word, and the editor of social-i

The Colour of Nonsense takes its narrative thrust from The Emperor’s New Clothes, where seeing and believing are complicated by people’s willingness to be deceived. In this case the invisible clothes are an invisible artwork commissioned by a tulip obsessed millionaire and the artwork is, at first, a screaming success…

We see people drop out of and into projected video, interact and converse with it. But do we ever really believe they just jumped out of the screen? No. Our reason tells us otherwise, we register that and move on.

There seems to be something deep about the ideas at play here. If seeing is believing, and you cannot see the thing that is to be believed… what do you do? Play along? Stand alone and risk being made a fool? By the end of The Colour of Nonsense people start to believe their eyes and see nothing when they look at the invisible artwork and the show ends in a panic. This seems to me to be the crux of the problem.

For all of its skill and narrative creativity The Colour of Nonsense fails to really look at, open up, a potentially fascinating ground where seeing and believing can be held up, pulled apart. Instead, with some competent skill we get a slight taste of what it is like to see and believe, without ever being satisfied as an audience member that something has been changed/learned/inspected/analysed. Instead, the surface was tantalisingly scratched but the piece was always subservient to the humour, grotesquery, theatrical tricks and technology which are Forkbeard Fantasy’s trademark.

Rick Bollinger is a Kent based theatre practitioner and writer

The Writing Performance Project took place 27 September – 10 November 2010, hosted by the Hazlitt Theatre, Maidstone and Canterbury Festival. It was led by Cathy Westbrook on behalf of PANeK, and by Beccy Smith on behalf of Total Theatre Magazine, assisted by John Ellingsworth and Cassie Werber.

Total Theatre Magazine is interested in developing further Writing Performance modules with other partners. If you would like to discuss this, email editorial@totaltheatre.org.uk

PANeK (Performing Arts Network Kent) is a countywide network of practitioners, promoters and organisations that aims to support and develop new theatre and performance in Kent. www.panek.org.uk

PANeK’s hosting a discussion (in Open Space) on the performing arts infrastructure in Kent at: Gulbenkian Theatre, Canterbury 12 January 2011, 10am-1pm. To reserve a place, email cathy@panek. org.uk

PANeK is funded by the national lottery through Arts Council England; Kent County Council; East Kent Local Authority Arts Partnership; and the Gulbenkian Theatre, Canterbury University.

Beccy Smith and her team of writers all saw Forkbeard Fantasy’s The Colour of Nonsense at the Theatre Royal, Margate on 23 October 2010. See over for the reviews. www.forkbeardfantasy.co.uk