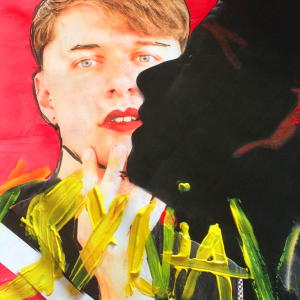

After seeing I want you to admire me/but you shouldn’t, Ciaran Hammond talks to Dirty Rascals Theatre’s artistic director Pavlos Christodoulou and performer and maker Tom MacQueen about what makes this emerging company what it is.

When did Dirty Rascals start and who was there at the beginning?

PAVLOS: So in 2015 we became incorporated, but we were originally a duo, who were at UCL together studying philosophy, but we were very active in the drama society. We’d just taken a play to Edinburgh and we had become slightly disillusioned with the wonders of academic philosophy and we wanted to try new stuff out.

When we started it was me and Jeremy Wong who was executive director but now he’s working for Improbable, full-time.

We’ve done a lot of work in quite a short amount of time: our first show was in 2016, which was a Mike Leigh-kind-of-style, improv, it was two intersecting monologues. Then we did some new writing.

This project I want you to admire me/ but you shouldn’t, which has had lots of other iterations, has become a sort of mainstay, whilst doing lots of other work – we’ve got several other projects on at the moment as well.

You mentioned studying philosophy, was there any particular body of thought that was implemented into I want you to admire me/ but you shouldn’t?

PAVLOS: This show actually started as an adaptation of a Kafka’s The Hunger Artist. The story is very murky and is about the Hunger Artist’s desire to keep starving for longer than the audience want him to. So we created a show that was about us trying to tell that story, and bring in moments of our own failure, as part of our storytelling. Then from a showing of that at the Wandsworth Fringe, we then shifted quite considerably whilst retaining the core ideas that were at play into this gameshow format which we showed at New Diorama when we were Emerging Graduates there, and then at CPT, then at Brighton Fringe and now at Vault Festival.

What has the most formative experience been for you guys as a company, so far?

PAVLOS: Last year I was feeling a little bit restless, because I felt that while we had produced work at a rate that was maybe normal for a starting company, there were long periods of time between rehearsing and performing that left me feeling quite unsatisfied. So I started a company night at Rosemary Branch Theatre (Turbulence), where I’d make a different show every month. We made fourteen performances, starting in late 2017 finishing in late 2018. So having such a short time frame to make work and making it with lots of different artists every month was really exciting and removed a certain preciousness and desire for everything to be perfect. So for me, personally, that was the most formative. But the company very much functions as a collective, as well as myself there are also four associate artists – such as David who is in this piece as a composer. Everyone’s journey in the company is different which is quite important to me as well; it’s not a homogenised, top-down thing.

TOM: My involvement with Dirty Rascals was the first time where I made work that was informed by live art practice more so than theatre. I trained as an actor at Central after UCL, I was classically trained, which was great, but then I left and thought ‘This isn’t all I want to do’. I was interested in exploring this whole world of work out there. So Pavlos has been really important to me in introducing me to that and allowing me to explore it.

The piece feels like a play in terms of how the drama runs, but the live art elements were definitely apparent. It seemed like you approached it from a deconstructive angle, would you say there’s some truth in this?

PAVLOS: Yeah, as the show has had a lot of iterations, we played around with a lot of different scores and different game structures. And while a lot of that exploration ends up getting discarded there’s something that develops over the process of that. In that sense it’s deconstructed, but it’s deconstructed in practice rather than where we sit and talk about it. We don’t actually spend that much time talking about the ideas in the piece.

TOM: We don’t anymore, we did in the beginning.

PAVLOS: Yeah, whereas now it’s more like ‘let’s try this’ and if it works, it works and if it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

TOM: The show is about how the show works, rather than about themes or something.

PAVLOS: Yes!

What would you say the most influential artist has been for the company, and individually?

TOM: I saw a Forced Entertainment show around the time after we did this show for the first time, and there were some parallels there, in terms of pushing yourself and the patience of the audience.

PAVLOS: I’d say a couple. I’d say ZU-UK and Jamal Harewood. They’re very generous but provocative, participatory art makers. I’d I’m interested in the work that I’m doing being simultaneously warm and generous, where the audience don’t feel like they’re being judged, but at the same time being something that is provoking and slightly uncomfortable. I think it’s a really hard balance, but ZU-UK and Jamal are both artists that do that really well.

What do you feel has been the biggest change in the company’s artistic practice since you started?

PAVLOS: It’s massive! I find it so weird! I also work as an actor trainer, I just finished a Masters in Actor Training at Central, so I’m always obsessed with performers and performance, and I don’t really think of myself as much of a director. It’s like I’m battling with the idea of me being a director. So the first show we did was two very actor-led processes where they developed characters and we improvised monologues and that was it. And basically we shifted through doing more conventionally theatrical work and plays to now having a lot of focus on participatory work on politics and live art structures. So it’s been quite a big paradigm shift, and it’s happened very slowly over time, and different parts of the company’s work articulate aspects of that.

Two of the shows that we have on at the moment: one of them is called Crimson Wave: Craft the Resistance which is a feminist, craftivist rave space and then the other one, it was the second time Dad made your cheesecake that my heart sheared in two, which will be on at Camden People’s Theatre, and that is a very personal, autobiographical, live art, participatory piece. Both pieces exemplify something that is in a way a remnant of an older practice within the company to some extent. You can see the linearity, because it does have that participatory component.

What would you say the biggest change in the world of performance you guys are involved in has been?

PAVLOS: It’s weird because I’ve not really been embedded in the world for that long, and I really feel that what parts of it have changed are the parts I pay attention to, rather than the thing itself. It’s a difficult one… I would say that I feel like for whatever reason, there’s something about agency and the hotness of participatory work, escape rooms and that kind of thing that has felt like there’s a willingness on the part of audiences to become authors of their own experiences and that feels like a shift to me because I see it in the wider culture outside of performance work as well. It’s something that I’m quite excited about because I really like playing with audiences. (To Tom) what about you?

TOM: I agree with what you said initially, but I need to see more stuff first I think!

Dirty Rascals will be performing next at Camden People’s Theatre on 6 March with their piece it was the second time Dad made your cheesecake that my heart sheared in two.

Interview by Ciaran Hammond