When a show opens with its title character being dumped on the autopsy slab, it’s a fair bet that things aren’t going to end well. But Wattle & Daub’s brown-aproned sextet of performers – musicians, singers, puppeteers – are determined to have a good time along the way.

When a show opens with its title character being dumped on the autopsy slab, it’s a fair bet that things aren’t going to end well. But Wattle & Daub’s brown-aproned sextet of performers – musicians, singers, puppeteers – are determined to have a good time along the way.

They take on the apparently true tale of Tarrare, a French eighteenth-century circus freak who eats constantly (and eats everything and, really, anything) but can never be satisfied, and is recruited to the army to carry secret messages (by swallowing and regurgitating them), before ending his days in a vain search for a cure in an institution.

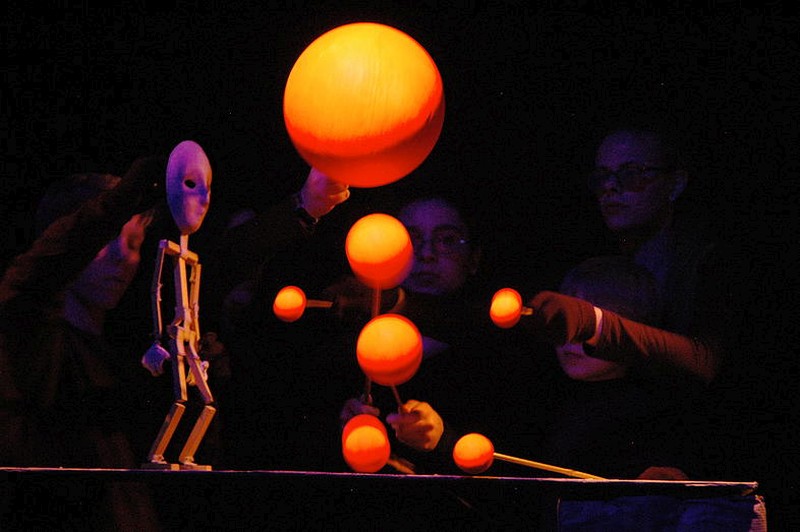

Tarrare is a grey-faced, falsetto-voiced, legless, lip-synch puppet figure with wondrously innocent staring eyes. There’s a rich array of other puppet characters as well: a pair of conjoined twins, just one of whom is madly in love with Tarrare; monstrous glove-puppet torturers; gigantic looming authority figures. There are some wonderful stage images along the way, and some witty and ingenious bits of puppet business.

Tom Poster’s music feels much closer to musical theatre territory than opera – it’s built around a set of songs, and there’s a lot of rich insistent melody, familiar harmony, and a fair bit of pastiching of various genres; the libretto is very given to witty rhymes. Musically, it’s all sumptuously performed on violin (Justin Wilman) and piano (An-Ting Chang) with occasional percussion touches, a combination that the rich texture of the score makes feel much fuller than it has any right to.

Although the puppetry is clever, detailed, and effective, the puppetry logics are not quite fully worked out, which is sometimes distracting. Of the two performers who are primarily puppeteers, Aya Nakamura works rigorously at a conventional neutral-puppeteer distance, while Tobi Poster spends much of the time looking over his puppet’s shoulder, quite literally open-mouthed in apparent horror at the puppet’s actions. The two performers who are primarily singers, Daniel Harlock and Michael Longden, work mostly standing well away from, but focused on, the figures they’re voicing – I found this hard to take to at first, often finding my own focus splitting between voice and action (and it certainly makes the lip-syncing puppeteer’s job visibly tougher), but just as it settled, the rules changed and the singers were also puppeteering (sometimes characters they were also voicing, sometimes not). There are beautiful moments of interaction between puppets and their operators; there are neat bits where a puppet character is represented by a popping-up head, or shares an arm with its puppeteer; there are nice moments where performers connect directly with the audience. But pleasing as they are these tend to feel opportunistic, solving immediate staging challenges, and there’s a niggling lack of consistent dramaturgical intention.

But the biggest stumbling block perhaps is the unceasingly sophomoric tone – there’s barely a moment that doesn’t have visual or verbal grotesquerie (sometimes full-on gross-out comedy) thrust upon it, and the gag (in more than one sense) is never resisted. Even where the music (with how much sincerity is hard to judge) is reaching for the heartstrings, the stage action is relentlessly undermining it with knowing humour. The show is, undeniably, loads of fun. But untempered with the pathos that these kinds of puppets are so very capable of (think of the work of Faulty Optic, who frequently worked in an ostensibly similar visual world but whose puppets always identifiably yearned and suffered), this means that we never really emotionally connect with Tarrare, let alone any of his freakish friends and accomplices (the well-meaning doctor comes closest, although his big number about curing the incurable is, again, too given to wit) and so when, in the very final bars, we seem finally to be asked to care, it is far too late.