Dorothy Max Prior profiles actor-creator Andres Aguirre, whose one-man show Lorcuedus is a physical theatre tour-de-force

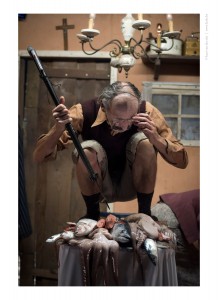

Ra-ta-tat tat. Ra ta tat. Poom. Poom. Poom-poom. A wild-eyed figure is regaling us from a balcony, his arms gesticulating, onomatopoeic outbursts fired from his mouth with automatic-rifle power and precision. After a few minutes we start to hear the sounds form into recognisable words: Trump Trump Trump TRUMP, Putin Putin Putin PUTIN. It’s a perfect play on the nonsense of political and military rhetoric.

Colonel Quince is the creation of Andres Aguirre, a Mexican physical theatre actor who for a number of years has been based in Italy. The Colonel wears the uniform of an indeterminate country: braided khaki, with leather jackboots, and a cap. He sports fifteen (quince) medals: he is the medals – Colonel Quince. He marches, he goose-steps, he ducks and dives, and he returns regularly to his balcony to berate the crowd. Are we with him? Of course we are. Do we love him? Of course we do.

Lorcuedus, Aguirre’s breathtakingly brilliant one-man show, takes us on a theatrical roller-coaster ride, exploring the archetypal figure of The Colonel. He is everyone you might imagine him to be, or none of them: it depends on your viewpoint. In his extremely long and thorough creation process, Andres Aguirre has researched the obvious European candidates – Hitler, Mussolini – but has also taken a good look at Russia and the Americas, from Chile’s Pinochet in recent history, back further in time to the dictators of his own country – the Caudillos or self-appointed political-military leaders emerging in Mexico in the 19th century, in the years after Spanish rule.

The show, Aguirre’s first full-length solo, and the Colonel character it revolves around, have been a long time in the making…

Andres Aguirre grew up in Guadalajara where, as a hyperactive child who could be a bit of a problem in school, he was sensibly guided towards physical activities such as martial arts, boxing, dance and gymnastics. And as if that was not enough, he also competed in swimming and cycling! Watching him onstage, the legacy of this impossibly physical regime is in evidence – the man has seemingly endless strength and energy. He was, for many years, one of the core team members of circus-theatre troupe Les Cabaret Capricho, encouraged by company co-founder Cesar Omar Barrios to learn circus skills and create a ‘numero’. Acrobatics, hand-to-hand and slackwire were all part of his repertoire. He trained mostly through short-form workshops and YouTube clips – with one unproductive term at Guadalajara University studying dance – but got to a point where he felt that he needed to engage in intensive, full-time physical performance training. ‘I started to ask myself why something sometimes works, and sometimes doesn’t, and the voice in my head said: it’s because you haven’t studied…’ Time for a change! On the advice of clown Anna Cetti, he took himself off to Italy, where he felt the quality of training would be higher than in Mexico, and presented himself to master teacher Philip Radice at the Atelier Teatro Fisico in Turin – offering to teach yoga in exchange for a place at his school. This was in 2010. Four years of serious training later, he started work on the Colonel character. He had previously met, and spent a lot of time as a companion, with the grandmother of a friend. He heard first-hand stories about the Second World War, which led him to further study of both European and Latin American histories, and to explore the way war was represented in literature and the arts. Writers he cites as influences include Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano (author of Las venas abiertas de América Latina / Open Veins of Latin America); and Viennese satirist Karl Kraus, author of Last Days of Mankind, which he loves for its absurd humour. An exploration of the relationship between visual arts and war/fascism led him to Picasso’s Guernica on one hand, and the Futurist Manifestos on the other. He also immersed himself in films, factual or fiction, about World War Two.

Meanwhile, Andres worked in the rehearsal room on transforming ideas and images into physical motifs. Military walks, for example: 300 observed and copied got reduced down to seven that eventually made it into the show! Photographs of soldiers with amputated limbs inspired a darkly funny and grotesque scene of ever-diminishing body parts. He put together the Colonel’s uniform, and working with the possibilities of that costume inspired the body language of the character. In 2014, he showed some early work in progress scenes at Philip Radice’s Atelier, then continued with the the slow but steady work of creating a full-length show.

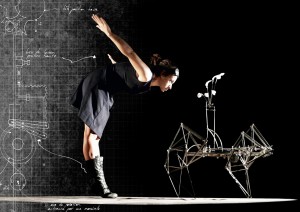

And what a show! Every scene has been worked on with military precision until it is ship-shape and ready for action. The extensive physical training – from childhood dance and gymnastics to circus and then theatre – shows in every move. Of course, it is upfront in the Colonel’s eccentric dances, and his military take on the Ministry of Silly Walks, or in that extraordinary ‘walking wounded’ scene, or an equally fantastic ‘ostrich with its head in the sand’ scene that is all chest and sex and puffed-up stupidity; but it is there too in every single small action or point of stillness: here is a performer who knows how to be onstage.

Throughout the creation process, Andres has worked without a director, filming himself and studying the results carefully to see what needs to be improved. ‘You have to sift and sift to find gold,’ he says – taking the analogy further by saying that the process is like alchemy: a constant reducing down to the essence. Aware that he needed an audience response, he tried scenes in a cabaret setting, or in public spaces. In the middle of the process, he realised that he was interested not just in war but in peace – in what dictatorships and oppressive regimes do to the soul of a people. And not only dictatorships, but life in supposedly ‘free’ countries: personal histories of race, economics and politics entered the picture. John Berger’s A Seventh Man, a book exploring migrant labour in words and images, influenced the work, as did a growing awareness of the plight of toxic masculinity – not just the worst-case scenarios of machismo in the Mexican and world psyche, but what he describes as the ‘tiny moments of machismo in the joking and teasing of everyday life’, and the use of language like ‘man up’. Now approaching 30, he started to re-evaluate his younger self and look to where he might make positive changes in his attitudes towards gender – and all this too entered the work. The show is a satirical reflection on war and politics, but more, it asks: where are we placed in all this? How easily are we swayed? How readily do we follow orders? Do we turn a blind eye to oppression if it suits us? As for the Colonel, the epitome of toxic masculinity: every day he’s at war with himself; every day he invents a new battle, and makes enemies of those around him. It’s no way to live. The notion of the destructive internal dictator – what Andres calls ‘the dictator of the self’ – started to inform the process.

Eventually, of course, you have to stop the researching and experimenting, accept that the process could be limitless but must be limited, and get the work out there. Then comes the Kool Aid Acid Test: the audience. Always a vital part of the equation, but in Lorcuedus the fourth wall is frequently broken through, and the Colonel’s engagement with his public – his pueblo – is vital to the success of the piece. When seen at the Ficho Festival in Aguirre’s hometown of Guadalajara, he does not fail the test. The audience are with Colonel Quince for the journey: from the first, surreal image – the Colonel upside-down, head literally in the sand, as if rocketed into the space – through to the numerous gobbledegook calls-to-arms from his balcony; the contorted dances and mimes; and eventually to the extraordinary last scenes where he orchestrates us flinging our shoes on to a stage filled with earth, a humorous moment that suddenly changes tone when we view the bombsite that we’ve created…

There are some people who may well have created three or four or more pieces of theatre in the same timespan – five years – that Andres Aguirre has taken to make Lorcuedus, but the ‘slow art’ approach has really paid off here. Physical theatre of the highest order. Congratulations, Colonel Quince – the first battle is won.

Lorcuedus was presented at the Alianza Francesca theatre in Guadalajara, as part of Ficho Festival, on 19 November 2017.

Dorothy Max Prior spoke to Andres Aguirre at Caligari Cafe, during the Ficho Festival 2017. www.fichofest.com

For more on Atelier Teatro Fisico di Philip Radice see http://www.teatrofisico.com/