A response to Os Bem-Intencionados / The Well-Intentioned, Brazilian company LUME Teatro’s new work in progress…

We are called into the ‘green room’ at the Sede de LUME – the company’s rehearsal and workshop space – and see a number of tables furnished with lime green satinette cloths, arranged in a circle around a dancefloor. In one corner is a trio of musicians, and in another a cocktail bar bearing a jumble of bottles and glasses. The bar has something of a late 1960s/early 1970s look. LUME actors are in the space – some in character and dressed accordingly (with that 60s/70s look also coming through into the costumes, which have something of a psychedelic vibe), some in a half-dressed state, and neutral mode. I am directed to a table near to the musicians, and sit down to watch the arrival of the other ‘dancehall guests’ – at this work-in-progress run it is only members of the immediate LUME family who are attending. As the band strikes up a lively dance tune, and the actors circulate, greeting us and placing beer bottles and glasses on our tables, we eagerly await the start of the night’s entertainment.

It is Monday 21 June and I have just arrived in Barão Geraldo – I have come from Rio where, by coincidence, I have just presented a show that is also an interactive piece set in a mock-dancehall – so I am very keen to see what LUME have done with a similar starting point. Inevitably there are crossover points, in particular in the breaking down of the actor-audience divide and the play on dancehall stereotypes, influenced in my case by the film Le Bal, and perhaps in LUME’s case by the Brazilian film that similarly investigates a dancehall’s life, Chega de Saudade – and we can note here that Os Bem-Intencionados will premiere in the glorious União Fraterna dancehall in Sao Paulo where that film was shot.

But Os Bem-Intencionados is essentially a very different beast to these other dancehall investigations, not least in its central preoccupation with the question of what it means to be an artist – our seven LUME actors playing a bunch of dancehall regulars who each have aspirations to artistic recognition and stardom. Collectively, they are a group of well-intentioned wannabes. They have missed out on the big time, but haven’t given up yet – their moment may yet be to come. Os Bem-Intencionados explores the desperation of the obsession with fame that pervades our current times; and ironically reflects on what it means to be a performing artist.

The show is very different to other theatre work I have previously seen by the company, and is presented as a collaboration with director and dramaturg Grace Passô. I am pleased to discover through this and subsequent viewings that despite being (in some aspects) a departure from familiar territory for LUME it is, no doubt about it, a LUME Teatro show…

The piece has a fair amount of spoken text which, with my limited knowledge of Portuguese, I struggle to understand – but it is a work rich in physical action, visual imagery and music, so plenty to appreciate. And I would also argue that much of what we understand about a given character or situation, in real life or in theatre, is perceived as much through the semiotics of vocal tone, phrasing, and gesture than through the semantics of the spoken language. So I feel that even without seeing a translation of the script, I have really experienced the work presented.

And so, on with the show…

There’s some minutes of general ambience and scene-setting, the music playing and the dancehall regulars (LUME actors) circulating – inviting guests in and making them welcome. Then, a change of tone and Ricardo Puccetti takes the floor. There is a man, he says, sitting here at a table in the dancehall (he points to a bare space), who is raising his arm to attract the waiter’s attention, impatient but perhaps too self-effacing or nervous to really insist that he gets this attention. Jesser de Souza skids across the floor bearing a table aloft, places it in the space, and with a flourish adds a tablecloth and a chair. Ricardo is still in storyteller mode, holding his arm aloft in an illustrative manner, but at some point over the next few minutes he dons a multi-coloured chiffon shirt and a wig to become that tall and lanky and somewhat nervous man with the raised arm, Márcio Martin. Meanwhile, Jesser’s character Gonçalves Rodrigüez – an over-cheery friend-to-all-the-world who desperately wants to have a good time, but is harbouring an inner melancholy – juggles a flurry of thrown bottles to set upon the table. He wears a red suit and a rather loud shirt, and also sports a wig. Márcio and Gonçalves, so different in size and stature, make for a comical pairing, played upon with a clown-like intention by the two actors.

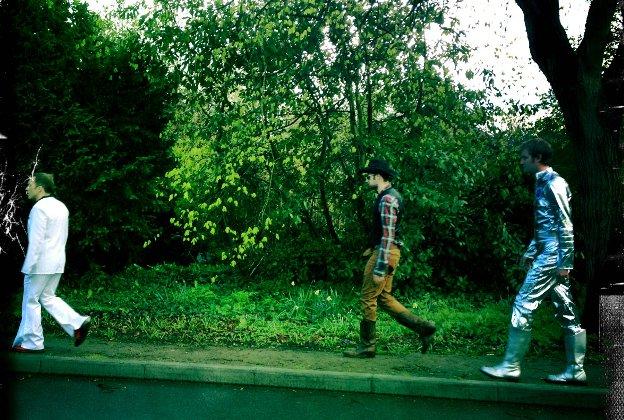

One by one the other dancehall regulars arrive to sit at the table. There’s Nataly Menuzes (Ana Cristina Colla, resplendent in a curly blonde wig) for whom ‘beleza e tudo’ (‘beauty is everything’). She’s a wide-mouthed, wide-eyed, curvaceous lady who laughs loudly, gesticulates wildly, and flirts madly with all and sundry. Maria Alice Elise (Raquel Scott Hirson) is a girlish woman for whom the word ‘kooky’ could have been invented – a scatty whirlwind of a person (dressed in shades of pink and purple, with hipster shorts and halter-neck top exposing her bare midriff, a jaunty cap on her head) who is constantly checking her mobile, talking in a simpering sing-song voice, scoffing chocolate bars, and tossing her shoulder-length locks petulantly.

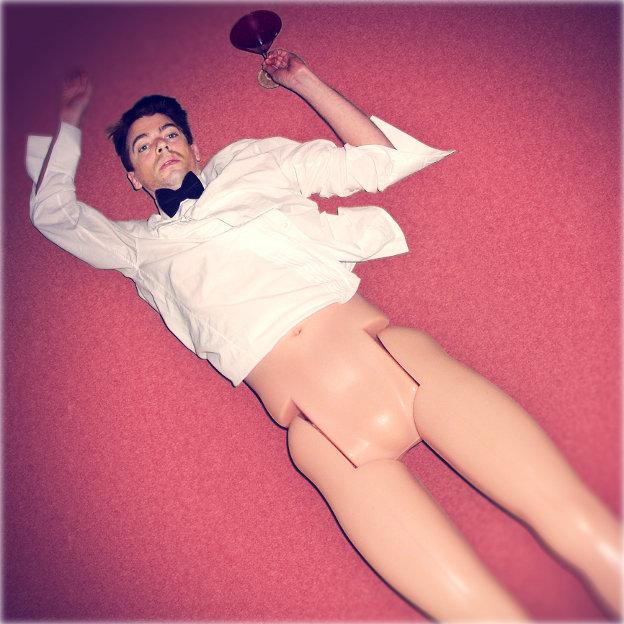

Maria Alice’s friend Melice-Z (Naomi Silman) gets dragged onstage prostate, by her legs – as it would seem is often the case, she is too incapacitated by drink and drugs to get there under her own steam. Having arrived just about in one piece, she is propped up on a chair only to almost instantly collapse in a heap, an elongated arm trailing from the chair, with a cigarette dangling from between her fingertips. It’s hard not to think of Amy Winehouse. Rodrigo Omett’o (Renato Ferracini) is another wigged man – a rock-n-roll wannabe, tight-trousered, furrow-browed and brooding, eying up the ladies with what he hopes is an alluring come-on. A little apart from the rest of the group is Dagoberto Leão (Carlos Simioni), an older man, handsome and aloof, dressed in a white suit, flowered shirt, and Panama hat. Dagoberto seems to pride himself (like the lion he is named after) on being king of the pack, but chooses for the most part not to get too drawn into the dancehall shenanigans. He often stays at his own separate table, reading a magazine, ignoring his colleagues. It would seem that for him, his own fantasy world (be it sexual, or the lust for fame) is more important than the sordid realities of daily life. Dagberto has a mic in front of him, and he soundchecks his voice, asking us if we can hear him. He reflects on the eccentricities of his colleagues, and sings us an opening song. We are readily drawn into the world of the well-intentioned, where fantasy and reality collide with a bang…

The show is divided into two halves, with an interval (or perhaps an ‘interlude’ or even a false interval – more on that later!) dividing up the two very different ‘acts’. In part one, spoken text plays a larger part as scenes are set and characters explored – although as I reflected earlier it is arguable what proportion of any ‘story’ is learnt through the language of words. For my part, there is a little too much text – and I am willing to accept that it may well seem this way because I don’t understand enough of the language spoken to really appreciate the words, but I do also feel that often the physical actions, gestures and visual images are doing the job well enough anyway. Part two sees a stronger reliance on the more ‘usual’ LUME non-verbal languages of movement and ensemble physical theatre. In both sections, the live music and song provides a throughline.

On this first run that I see, I find myself drawn most strongly to the Márcio and Nataly characters (as played by Ricardo and Cris). Their stories seem to be at the heart of the action – and without offering any ‘spoilers’, the traditional Aristotelian theatre requirements of conflict, denouement, and resolution seem most clearly played out in their journeys.

I get to see a second run on the following night (Tuesday 22 June), and it is interesting to note how different the show feels on this occasion. Partly of course because any live show or rehearsal is very different on successive nights; partly because the actors are now more in the flow of the work (Monday’s run was the first after a long break in rehearsal schedule); partly because interesting changes have been made, including to the ‘interval’ dilemma – which I am coming to, I promise; partly because I am sat at a different table, so have (literally) a different view; partly because I now have some knowledge of the piece, a grasp of its overall shape, so am taken by different aspects. So on Tuesday night, I find myself – for whatever reasons – drawn most strongly to the enigmatic machismo of Rodrigo (Renato’s character), and the flighty Maria Alice (played by Raquel).

Melice-Z (Naomi) and Gonçalves (Jesser) are consistently strong presences on both nights – although Jesser’s Rodrigues is on particularly good form on Tuesday. Simi’s Dagoberto is hard to grasp as a character – he is, in any case, pitched as someone a little apart from the rest of the dancehall regulars – yet is obviously the ‘glue’ that holds the piece together through song and commentary, and whose own personal journey is perhaps the most tragic (although bathos and pathos might be more appropriate terms than ‘tragedy’).

There is a wealth of imagery to reflect on after the runs. On night one, I am sat at a table at which a wild massacre of a bunch of roses occurs – on the second night I take voyeuristic pleasure in watching someone else jump in terror as a knife flashes past them. I enjoy the way objects are used in the piece – that knife has many and various roles: chopping the flowers, drawing a sinister outline round a fallen body (itself a repeated visual/physical motif), and stabbing a polystyrene wig-head holder with venom. Mirrors, large and small, are important to the piece, as are shoes, handbags (and their contents) and jewellery. And those wigs are used almost like masks – donned and doffed to put on or take off a character; to play with notions of the real and the artifice; to explore notions of exposure and embarrassment. Drinks bottles and glasses (tall, small, plain and coloured) act as more than props, becoming players in the action and signifiers of the characters’ states-of-mind and intentions. They also act as conductors, relaying energy between the worlds of the actors and the audience: the beer bottles placed on our tables contain real beer (or even cachaca for one lucky table!), and we are encouraged to drink throughout the show; bottles are thrown and caught, crashed into and broken; characters play out their pensiveness with circling fingers that set the glasses singing; and a very lovely scene exploring Marcio’s social inadequacies is played out with a bottle of champagne, in an interaction with a female audience member, who is cast as the object of his desperate romantic desires. Inevitably, the flirtation backfires as Marcio screws up, the wrong words escaping from his lips – a moment of desperate humiliation that sets him on course for an explosion of pent-up frustration…

As for the physical language of the piece, there is much that would be familiar to LUME audiences and some that is perhaps less familiar! A scene that depicts some of the characters at some indeterminate point in time in the future, uses costume and props (a terrifying Botox-faced transparent mask, a back-to-front jacket with shortened arms clutching a pair of champagne flutes, a large woven basket thrown over a head, a veil covering a bent-over body) in a beautifully stylised dance depicting ageing bodies, fading glamour and the endless repetition of this hedonistic lifestyle (’You’re are so repetitive, so repetitive, repetitive!’ screams Nataly at an earlier point in the show – setting up an interest in repetition as both dramatic theme and theatrical device).

In other scenes the familiar LUME physical theatre ‘toolbox’ is employed to great effect – the use of different levels in the space (a woman on top of a stepladder; a woman crawling along the ground); the ‘panther’ roda or circle as things go a little too far, and one character is stripped of her dignity by a grunting and growling herd; the use of the ‘hero and chorus’ technique, for example in a scene where Raquel’s character receives an important phone call offering her an interview or audition, and the whole group shuffle round her, agog for more information. Gestural movements are repeated and enlarged upon from one section to another: that desperate and hopeful raised arm; or a baying laugh exposing wolf-like teeth; or a stifled Geisha-like giggle with hand to mouth). Popular dance moves – from samba and rumba bolero to tango and tap – are deconstructed and stylised, with one delightful moment being the terribly-tall and lanky, high-heeled (and inevitably unstable) Melice-Z (Naomi) and the dapper and fast-footed, but far shorter, Gonçalves (Jesser) dissolving to the floor in an undignified heap, as what should have been a passionate Rudolf Valentino style tango oversway goes a little wrong…

The music is a key element: the trio of live musicians (keyboard, accordion and percussion) keep things moving with a swing, under the expert leadership of musical director Marcello Onofri; providing accompaniment to both the physical action, and the torch songs sung by Dagoberto – which include a rather splendid rendition of Frank Sinatra’s My Way.

Oh and that interval question! It was reflected on after the second run, and also in a rehearsal I attended the day after. Apparently, in an earlier incarnation, the company had played with the idea of two separate acts in this 120-minute show, with a clear-cut interval (announced by the band leader). For these two runs, this had been abandoned in favour of a more fluid sort of quasi-interval, with some of the actors staying in the space, but the audience free to leave (to smoke or use the bathroom). The outcome of the discussion and reflection would seem to be that in its next incarnation, the company will play with the notion of a ‘false interval’ or interlude, in which the band take a break and recorded music plays, but actors and audience stay in the space, with the actors/characters exploring a different relationship to space and audience in that interlude.

Sadly, I will not be around to see this next stage – but I return to England happy to have at least witnessed the story so far, in both the very early rehearsals I sat in on in late March, and these far more advanced ones in late June. I have been very glad to have had the privilege of attending these rehearsals and runs – and to have played a small part in the development of the show by providing a few short dance classes in ballroom dancing and tap!

Rehearsals have stopped for now, the company and director busy with other projects, but on 12 July they resume work. And on 27 and 28 July 2012, Os Bem-Intencionados will premiere at that aforementioned beautiful old dancehall in Sao Paulo, before settling in to a two-month run throughout August and September at SESC Pompeia (also in Sao Paulo).

One of the things I felt seeing those runs on two nights in succession is that this is a show that could well be seen a number of times. The different viewpoint depending on where you sit, and the small personal interactions between actors and audience that change from night to night, make for a potentially radically different experience of the show. And there is so much to take in that just once is not enough. So if you have the opportunity, I urge you to go and see the show not just once, but on more than one occasion! There will be plenty to entertain you as you drink in these stories from the frontline of frustrated romantic intention; plenty of food for thought in the reflections on thwarted artistic ambition; and plenty to nourish your heart and soul in this expose of the fears, failures and frailties of these seven characters.

We are all, we realise, like them – all well intentioned, all doing our best in this dance of life, despite the obstacles on the path. And we all, ultimately, do it ‘our way’.