On 12 December 2022 came an announcement: ‘All in the Desperate Men family are incredibly shocked and saddened to announce that Jon Beedell, founder member and co-artistic director, has died. He passed away in his sleep on Saturday night/Sunday morning. We have been overwhelmed by the outpouring of love for him. Irascible, irreverent and irreplaceable, he made mincemeat of flimsy reality…’

Four of Jon Beedell’s friends and colleagues from the Outdoor Arts community – Edward Taylor, Bill Palmer, Lorna Rees, and Jeremy Shine – show their appreciation for this maverick and much-loved godfather of UK street theatre

Edward Taylor writes:

You had to be extremely bloody-minded to do street theatre in the UK in the early- to mid-1980s. Audiences could be indifferent, even openly hostile, and often the promoters neither provided any facilities nor showed up to see what you were doing. Of course it wasn’t all like that – we’re not masochists so there was obviously enough positive feedback to keep going, and sometimes the sheer ridiculousness of a situation that has got hopelessly out of hand can, if the performer is adept enough, create situations impossible to replicate anywhere else.

Jon was one of the most bloody-minded of us all. He’d worked in Europe so had experience of a street theatre circuit that was so much more than groups bunged out on Saturday afternoons to sink or swim. I think that experience was part of what drove him and meant that a cynical attitude which was quite easy to fall into was tempered with an idealism about creating a better and more effective context for the work he wanted to do and see. He very often said that street theatre could change the world.

Certainly the festivals and events he and Desperate Men co-director/performer Richard Headon (with the help of many others of course) created in later years realised that idealism. Over-arching narratives unfolded over several days which allowed for community involvement and the participation of other companies to enrich the experience of the public.

I first saw Desperate Men performing Eggs & Enemies in Manchester in 1983. A great show but throughout it I kept wondering where I’d seen Jon and Richie (Desperate Men co-founder Richie Smith) before. In turned out that Jon was wondering where he’d seen me and Whalley Range All Stars partner Sue Auty before – and it turned out that we’d all seen each other in the Melkweg in Amsterdam in 1981. Sue and I had been helping build and perform a big site-specific show with Dogtroep, and Jon and Richie had been running or attending a workshop in the daytime.

I last saw Desperate Men perform Generations in Manchester in 2022. Jon wasn’t in that episode of the show but was up to give notes. It was typical of the work they did – not at all what you expected, not pandering to the audience whilst not being too remote either, and giving you something political to think about whilst at the same time not piously wagging fingers. A difficult trick to pull off, but they managed it.

The talk at the time was that Generations would be the last Desperate Men show, but when I asked Jon about this he replied ‘never say never’. We will not see his like again.

He’s left us with a fine legacy of work.

My favourites? The Formicators at Roskilde Festival in 1995 where a team of five ants with a laboratory on wheels picked up and bagged the detritus left by festival goers. Absolutely ridiculous and at the same time quite revealing.

Slapstick & Slaughter at MintFest in Kendal in 2014 where Jon and Richard used the absurd rebellion of Dada to illustrate the meaningless horror of war, and proof (if you need it ) that if you’ve got an audience onside, the seemingly endless repetition of one word from the song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ can take them to places other theatre companies can’t manage.

Edward Taylor is formerly of Whalley Range All Stars and is now specialising in kamishibai and comic book stories.

Jon Bee & Me by Bill Palmer:

I knew Jon for around thirty years and along with the others of The Desperate Men company, we’d shared the same touring circuit for all that time. Over those years we had met in more festival dressing rooms and late-night bars than I care to remember or admit to in print.

These encounters have often been years apart, such is the life of the traveling performer.

Scene: Glasgow pub interior, noisy, crowded.

Jon: So, are we getting this band together or what?

Scene: Manchester café interior crowded, steamy, two years later.

Bill: Yes, soon man, it will be soon…

Picking up the threads – effortless.

That’s how it had been until recently when Jon and I spent the best part of a week together. Ever since we discovered our shared love of Jazz and Blues, we had been talking about a musical collaboration of some kind. This was the first step, testing the water – a chance to wear our dreamer hats. Over a few days we played some tunes, Abbey Lincoln’s version of ‘If I Only Had a Brain’, re-titled by Jon ‘If I Only Had a Brian’ – and Thelonious Monk’s ‘Blue Monk’ re-titled by me ‘Blur Monk’. The rest of the time was spent shooting the breeze, riffing about creativity, old age, family, politics and travel.

On a trip to our local wine merchant, Jon fell into easy conversation with the owner about the relative merits of the Viogniers they had in stock. We emerged with three. Jon was effortless with strangers, immediately achieving a rapport. It was the same in the bakery. I suppose it was the result of a life spent performing on the street, engaging the public – he was a great talker, a great listener.

There is a shared folder on my Google Drive with the music we were working on. It’s titled ‘Jon B & Me’. I don’t think I will delete it. There is also a last bottle of Viognier in our fridge, left as a parting gift. We will lift a glass to him.

Bill Palmer is a founder and continuing member of Avanti Display.

Lorna Rees writes:

I’ve only known Jon Beedell for about 11 or 12 years, which I know is a tiny amount of time in terms of his career.

For the London Olympics, Desperate Men created the enormous three-day-long Battle for the Winds performance with Cirque Bijou. I can’t really describe the scale of the work involved in this huge project: seven counties, thousands of artists and performers involved. We formed a huge cadre of ridiculous wind collectors riding strange cycles throughout Weymouth and Portland collecting wind for the sailing events.

I directed and produced day two on Portland, an installation piece made with community dance and sound artists. I also had a hugely enjoyable time performing on the Dorset Wind Cart in a ensemble of eight other street artists/musicians: absolutely one of the most enjoyable, silly, improvisatory and incredible things of scale I’ve ever done. It was all a ridiculous, playful, messy, joyful experience – and for some of us (including me) rather life changing. It inspired new collaborations, confidence, partnerships, and above all a sort of permissive playfulness. Jon and Richard from Desperate Men (with Billy Alwen) created a meta-narrative which allowed for different artists to add in to. Jon provided an artistic overview, extending a deeply enthusiastic and facilitatory attitude to the whole project.

I’ll never forget (probably illegally) jumping in the back of the van post-ceremony riding back to the Weymouth holiday park we were all camping in. The event was truly extraordinary to be part of, and a random bunch of us including Jon himself, Phillipa Haynes, Doug Fransisco, Robert Lee, Jon Croose and a bunch of other street theatre artists, circus performers and technicians all piled into the transit in search of the after party with remnants of paraffin and squibber kit left over from the wader’s fire procession into the sea. We were all giddy with adrenalin and fumes on the highest high, a sense of having accomplished something utterly ridiculous and extraordinary – which we had. Which Jon had.

Lorna Rees is artistic director of Gobbledegook theatre and all-round artistic activist.

Jeremy Shine writes:

I first worked with Jon before he was Desperate – well, he might have been but we were all a bit more optimistic in 1978 B.T. (Before Thatcher) when he performed at the first ever comedy festival at The Drill Hall in London. This was in the days of ‘alternative comedy’ – i.e. before it got funny and before the rise of stand-up, comedy clubs, and stadium gigs – and always ahead of the zeitgeist was Jon, which is probably why he never got rich and ended up on the streets!

I’ve lost track of the number of times Jon performed for me – probably in every festival I organised in numerous locations from early indoor shows in Manchester at the precursor to Greenroom right through to Permission Pending in Manchester city centre in 2019 which, of course, ‘never happened’ because the email telling the authorities about it mysteriously got stuck in my draft box – although I thought I saw a familiar shape rolling round the city that day!

The thing about Jon is that he never lost his radicalism, both personally and artistically – unlike most companies (indoors and out), the Desperates never settled into a formula and no two shows were alike, so you never knew what was coming although you did know they’d be interesting and usually really good.

My favourite show was Slapstick & Slaughter which demonstrated that even after 40 years they still had it. I loved both the content and that it was inspired by Dadaism, probably the most important artistic movement of the 20th century. Without Walls made a call-out for shows relating to the First World War and was flooded with applications that seemed like pitches to Radio 4: ‘a dramatisation of my great aunt’s diaries about driving ambulances behind the trenches’! Slapstick & Slaughter was the opposite – a show that dealt with the lunacy of war in a style influenced by the horrors if it and one that required the audience to concentrate. One of my pet hates is ‘family shows’ – code for children’s shows that adults have to suffer through (a Beedell-style rant – sorry) because I think, with rare exceptions (relating to content), all street shows appeal (or repel) audiences of all ages. But I felt that children wouldn’t enjoy this one, so was surprised when a nine-year-old girl told me it was her favourite show at SIRF that year. I’d forgotten the cardinal rule: ’trust the artist’.

Street arts is, by its nature, ephemeral – we leave no buildings or monuments. But I hope that Jon’s life and work will leave a legacy of inspiration for artists: fluffy chickens (literal or metaphorical) – get off your stilts and innovate, challenge convention, and above all be brave.

Jeremy Shine is former artistic director of Stockton International Riverside Festival, Kendal Mintfest, Manchester Streets Ahead, and Feast – and is still creating outdoor events with MIA.

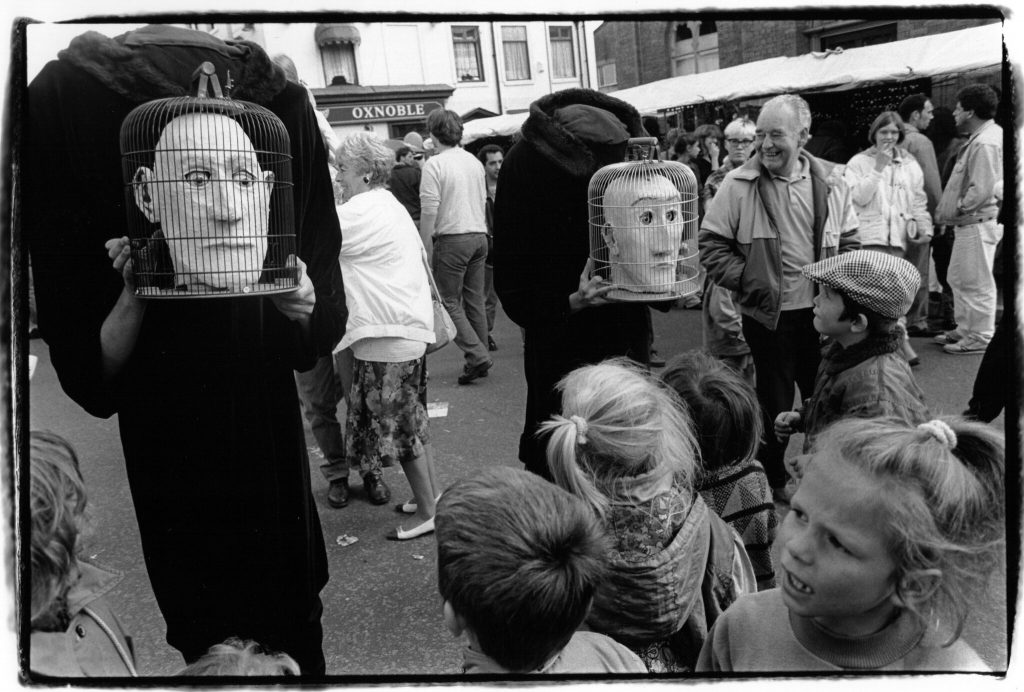

Featured image (top of page): Desperate Men, Slapstick & Slaughter performed by the company’s co-artistic directors, Jon Beedell and Richard Headon.

Desperate Men has been at the forefront of outdoor arts in the UK since it was founded in 1980 in Berlin by Richie Smith and Jon Beedell.

See the Desperate Men website, which includes an archive of the company’s work over the past 40 years. https://desperatemen.com/