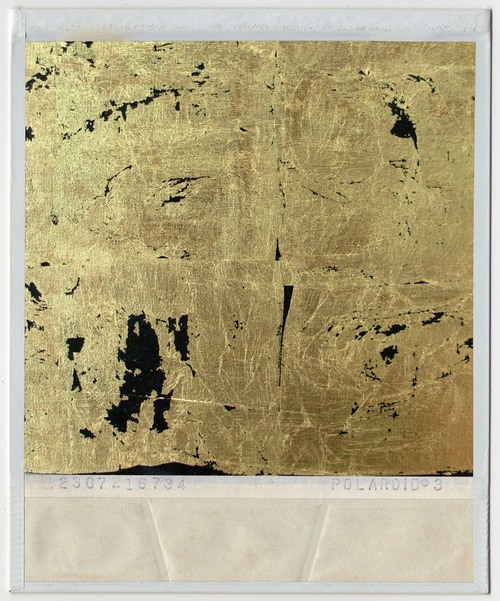

Photo – Yiota Demetriou

I recently attended the live art platform Tempting Failure. In its aftermath the provocations that my encounter raised have stayed with me. The platform’s curatorial approach and realisation of ‘risk’ have occupied my thoughts. And it has led me to ask the general questions: who are live art platforms really for? And, what is the audience’s position?

Tempting Failure is ‘a platform for live art, noise art & performance art’ conceived in 2011 by Artistic Director, Thomas John Bacon. TF2014 took place at the former Birdwell Police Station, in Bristol, currently occupied by the Island arts centre. The platform considers ‘risk, failure & transgression’, beyond their negative connotations, focusing on the progressive potential they hold to push preconceived barriers of live art practices. TF programmes a wide range of artists and art forms, addressing ‘live art’ as a non-limiting umbrella term.

This year, the festival ran from 3–8 November, comprising of workshops, artist talks and performances. For geographical reasons, my attendance was limited to the first half of the final night. I am therefore conscious that my encounter refers to a very limited scope.

I arrived in Bristol just in time to attend the Artist Panel Talks. On the panel on ‘FLESH & femininity’, artist Hellen Burrough spoke (and I paraphrase) of testing the limits of self, as a performer, to reclaim her female body. As an audience member her statement has interesting potential. Substitute ‘performer’ with ‘audience’ and it adds an interesting new dimension, in terms of considering the audience’s participatory position in platforms of this kind.

Night fell; I entered the former police station. I made my way down towards the old prison cells in the basement. The space itself is fascinating. Dark histories cling to the walls. I immersed myself, letting my exploration of the space determine my encounters.

I arrived at Cell 4, Gillian Jane Lees & Adam York Gregory’s durational piece Constants and Variables where I observed a woman in a white paper dress repetitively transferring black ink from a filled cylinder to an empty one, inevitably spilling in the process. The action was logged by a man stood opposite her. My appetite for risk was dissatisfied by the observational role I had to play.

I made my way past a swarm of confused audience members, down a narrow corridor marked by a performer sat impassively at its end. The corridor led to Cells 1-3.

Progressing down the corridor, I participated in Hannah Millest’s In Situ, a one-on-one performance that explored ‘suffering and empathy’ in an intimate environment. The performance was designed as a series of choices – rules – intended to prohibit the participant from being ‘passive’. In juxtaposition to the previous performance I was delighted to be given greater participatory responsibility, but the performance itself lacked depth. Fabricating intimacy by asking pointless questions, such as ‘how old are you?’ and, subsequently, presenting a choice of objects that results in the performer being repetitively slapped is a depthless investigation of ‘risk’ and intimacy – a one-dimensional attempt to manipulate feelings.

From my position as an audience member, it seemed that the curatorial descriptions of the platform had set me up to expect more.

I made my way towards the performer who marked the end of the corridor; I arrived at Hancock & Kelly’s Gilding the Lily. I approached the performer and he gently pushed a sheet of paper towards me: instructions for the one-on-one to come – an agreement to seal my genitals in gold. I signed the piece of paper and waited my turn.

In front of me: a line of women. Hellen Burrough’s statement echoed in my mind and the sight made me proud.

I gave the performer my hand and she led me into the cell, shutting the door firmly behind me. In the room, a man stood with his back towards me. I reminded myself of the instructions, ‘stand behind them, offer them your hand, they will guide you through what is to come.’ I took my place behind him, I offered my hand and he took it firmly, and placed it on his chest. I felt his heart beat, which calmed me.

What followed were a series of choreographed actions, oppressive in nature, to which I submitted. As agreed on paper, I exposed myself. He smeared lubricant on my genitalia. He applied gold leaf and began to sculpt it. I was mesmerized by the action he was performing on me. Once the action was complete and my genitialia was sealed, the encounter was documented. I left the cell with a gold sealed vagina and a polaroid as memento. The engagement with ‘risk’ was complex and I tested my own bodily limits by exposing my vulnerability to the touch of a performer. I had tested my limit as an audience member and felt physically and emotionally empowered.

These were just three of a wide array of performances responding to the platform, which I was able to attend.

Tempting Failure aims to programme artists that raise questions of risk. But for a platform to curate risk with the audience’s position in mind perhaps proves more difficult. At a time when general audiences are gaining confidence and interest in the risks that come with participation, the link between curating and realising needs to be examined. Hancock and Kelly proved that there is a real exciting potential in curating risk, but for the potential to span a whole platform the curatorial approach needs to be examined and clarified. Who are platforms really for? And, what is the audience’s position?

It’s arguable that platforms can function successfully primarily for the artists. But, I do think that curatorial clarity in addressing the audience’s position is important in order to realise a platform’s aims. And, in the case of TF, in order to avoid ‘risk’ itself coming across as jeopardized from my position of a seasoned live art audience.

I left Tempting Failure with my vagina sealed with gold – a reminder of the exciting potential that exists when curating platforms for risk.