In 2012, Jon Haynes & David Woods decided that their next show would be a family drama. They quickly discovered that mental illness played a central role in both their lives, and set about investigating how their experiences could become theatre. A trip to Finland was pivotal to the making of the show. At a conference about the Open Dialogue method of treating schizophrenia in Western Lapland, they took part in a series of treatment meetings (in character) with powerful, emotional results.

In 2012, Jon Haynes & David Woods decided that their next show would be a family drama. They quickly discovered that mental illness played a central role in both their lives, and set about investigating how their experiences could become theatre. A trip to Finland was pivotal to the making of the show. At a conference about the Open Dialogue method of treating schizophrenia in Western Lapland, they took part in a series of treatment meetings (in character) with powerful, emotional results.

Two years on, Sick! Festival hosts the premiere of its commission of the show, to sell-out audiences for this much-loved company. It is a very ambitious premise; an attempt to marry form and content by splitting the audience in two and giving them a simultaneous performance of two plays with the same characters but different action. Turns out it is too ambitious; by the second night they have scooped out a chunk of text and done away with the repetition of the opening scenes.

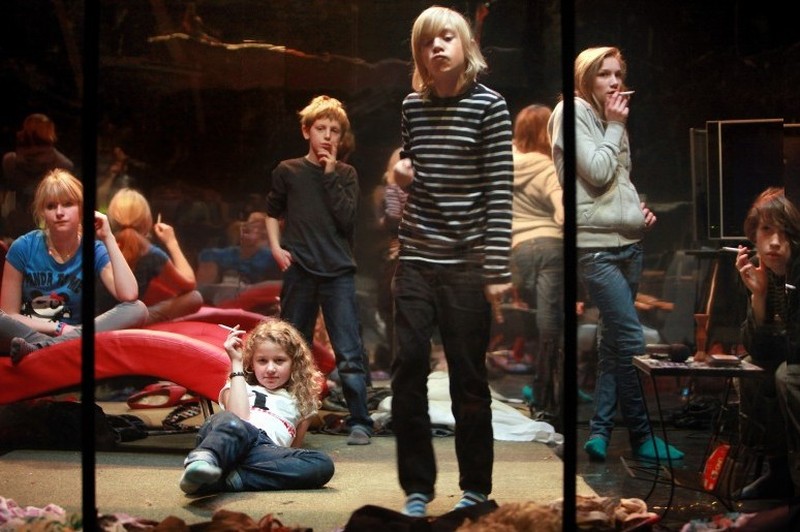

The family drama features two brothers, Rupert (Richard Talbot) and Richard (Jon Haynes) their father Graham (David Woods) and his new wife Jade (Patrizia Paolini). David also plays a doctor. We first meet them through a series of fractured vignettes, the doctor and his patient (Richard), the brother and the step-mother arguing over food. The set divides the action with a screen of windows through which we can see and just about hear what is happening on the other side. The intention is to create a kind of auditory hallucination, to put us in the place of the schizophrenic, witness to multiple voices and characters. There are bright, scrutinising lights (Mischa Twitchin) and a subtle sound design (Salvador Garza).

There is some great dialogue in these opening scenes. Richard’s delusions are delicious; he is a Nobel prize winning novelist, actually Nabokov and Edna O’Brien. He was born from Hitler’s frozen sperm. The doctor tries to get to the trigger of his psychosis… there is something about his brother’s death, but gets nowhere. Richard refuses the drugs offered. The characters move between the dividing screen, punctuating each other’s conversations, overlapping the dialogue and gradually building up a sense of who they are and how they relate.

In the second half, with the audience shifting ends, the full-blown family saga unfolds. This is richer stuff. The father is a gruff bully, his younger wife is trying hard to accommodate a new family with help from a variety of head-dresses, the brothers are fighting over who was closer to their dead mother. A heightened, melodramatic moment features a toilet roll dolly to comic effect and of course it all ends badly. Hallucinatory elements creep in; the dad puts on a weird bull mask, brother Rupert a tall pointy witches hat.

The performances are all strong; Paolini’s role as the unhinged mother, burping and hopping like a frog, is quite wonderful. Perhaps due to the day’s large-scale changes, the company did not seem perfectly at one with the material; I sensed some unease between them. Once fully embedded the relationships will flow and characterization become stronger.

In Western Lapland, schizophrenia has been successfully treated by people coming together and listening, talking and being open to difference. The person at the centre of the process is not seen as ill or troublesome; they have a set of problems that need help. Ridiculusmus take this as a metaphor for dramatic practice and make us all part of the discussion, part of the attempt to move forwards without buoying up the profits of pharmaceutical companies.

There are not there yet with this play, which was rather unready for a world premiere. It is a fascinating subject and the elements are all there for another piece of classic Ridiculusmus; thought provoking, adventurous and always a little, dare I say, bonkers.

Do you still suck your thumb? Is Peter ‘The Cat’ Bonetti still in goal? Are you in a west end musical yet?

Do you still suck your thumb? Is Peter ‘The Cat’ Bonetti still in goal? Are you in a west end musical yet?