Lisa Wolfe reports from the Dublin Theatre Festival 2013

Ireland 2013 is branded by a concept called The Gathering. It calls for the international diaspora to come home to the old country for while. It encompasses sport, aviation, business and the arts. There is the Garda versus the NYPD Boxing Tournament, The Irish Global Pub Owners Gathering and Cork Rebel Week. It is a great hunk of tourism marketing.

I’m not at all Irish, despite my surname, but hang it, I’m coming too.

Dublin Theatre Festival’s contribution to The Gathering is to feature Irish writers who lived outside the Emerald Isle. There is Eugene O’Neill (America) Samuel Beckett (Paris) and James Joyce (Zurich, Trieste, Paris and er, Bognor Regis). I travelled with my personal James Joyce and Irish history expert Peter Chrisp and discovered further ‘exiles’ during my three days in the City.

Day One: Friday 4 October

From the airport bus, through the new tunnel, past the new James Joyce Street and down to O’Connell, a stop right by Wynn’s Hotel. It looks Victorian, but was bombed in 1916 during the Easter Rising and was rebuilt a few years later. Wynn’s seeps history; it’s mentioned twice in Ulysses and three times in Finnegans Wake, and last month hosted an exhibition about the Irish Volunteers, the nationalist military organisation which was founded here.

But there is no time for complimentary tea or coffee – it’s straight round the corner to The Abbey theatre for play number one.

Written and Performed by Eamon Morrissey, Maeve’s House is an Abbey Theatre and Dublin Theatre Festival commission and world premiere.

His mother had often told him that the writer Maeve Brennan – an Irish exile, had lived in their house, boasted of it, kept clippings about her, but it wasn’t until he was in New York in 1966 as a young actor that Eamon Morrissey fully understood the novelty of the link between them. For many years, Brennan had been writing short stories and prose pieces which she set in that same Dublin house and described fondly and in great detail.

When he first discovered the writing about 48 Cherryfield Avenue in a story in the New Yorker, Eamon says ‘my entire background and childhood came leaping out at me’ and it’s easy to appreciate how strange that would be. Decades later Morrissey has pieced together excerpts from Brennan’s stories and reflections on his own history.

Maeve Brennan wrote stories about relationships that were often stagnant and bereft of affection: she had married and divorced a wrong-un, and had a hard life, ending up destitute, deranged and alcoholic. Her articles were more lively and entertaining, with sharp observation and a pleasing curiosity. This is great material for the stage. Here though, Morrissey doesn’t quite nail it and the performance falls somewhere between a conversation and a play. The writer’s own story is told anecdotally and Brennan’s more theatrically. Yet it stays at the same emotional level except for one episode, a fairly brutal story of man unable to grieve for his dead wife, where Morrissey shows his acting chops.

The staging is simple with a curved pew, a stool and pools of light. A backdrop evokes the New York skyline. There are some unnecessary sound effects – a ringing phone, kitchen dishes clattering – that reinforce the lack of an overall vision for the show.

It’s an easy hour, and Morrissey is always watchable, but it is like a soothing shade of grey. The Technicolor version of Maeve Brennan’s life has yet to be told.

Time for dinner and a refresher in the Stag’s Head (boy was that a big stag whose head is on the wall) then into Temple Bar and the Project Art Centre.

Next came Riverrun: presented by TheEmergencyRoom and Galway Arts Festival; adapted, performed and directed by Olwen Fouéré.

There is a low, electronic rumble in the room. Olwen Fouéré stands at the front of the stage, hands clasped together, smiling at us. Once everyone is seated and silent she takes off her gold shoes, steps over the elegantly trailing mic stand onto salt crystals, and becomes water.

So begins the most exquisite and captivating performance that I have seen for a long time. Joyce’s notoriously tricky language is sometimes completely opaque, sometimes ringing clear. Fouéré embodies all of its musical texture and character, capturing nuances, exaggerating sounds, riffing on the poetry of Joyce’s playful text. ‘Into the wikeawades warld from sleep we are passing. Four. Come, hours, be ours!’ The sound design (Alma Keliher) is beautiful, underpinning not overwhelming the voice which, whether in words or noises – Bulgarian style throat singing no less – is a joy to hear.

Most of the piece is done stage front and into the microphone, so when, at one point, Fouéré moves upstage, takes off her steel grey jacket and swings it around her head, side lit and majestic, well, that’s quite a moment. The lighting (Stephen Dodd) is stunning throughout, providing just the right level of grandeur to this wholly toned and tonal piece.

In an interview Fouéré said that she chose her text so as not to be too easy on herself or her audience. Had she just done the final monologue, of Anna Livia’s flowing out to the sea, it would have been ‘a bit too Molly Bloom’. So the play begins with the more difficult narrative voice from the first part of the chapter. It is a mind-boggling feat of memory and interpretation. Then we launch into Anna Livia’s journey – flowing into the sea is death for a river: ‘My leaves have drifted from me. All. But one clings still.’ Here Joyce conflates the autumn leaf with the page of the book – itself a leaf. Fouéré is now more female, constantly in motion, almost ululating, using her breath and her body in a gorgeously rich theatrical climax. A final word, from this circular novel, is left hanging, from an unforgettable face in a crystalline light: ‘the’.

After the show, Olwen Fouéré and some of the audience walk to the Millennium Bridge to raise a dram in a paper cup to the Liffey. Asked how she memorised so much of the chapter, Olwen says, ‘I read it aloud a few times, as I was compiling the piece. Then I found I just knew it.’

Day Two: Saturday 5 October

Mundo Perfeito, Three Fingers Below the Knee | Photo: Magda Bizarro

A swish tram to the Irish Museum of Modern Art near Heuston Station for an exhibition of work by Leonora Carrington. Leonora was another exile of Irish extraction; she ran off with Max Ernst and moved to Paris, but lived most of her long life in Mexico. An extraordinary artist and a key figure in the Surrealist movement, she painted intricate myths and visions, printed, wove and sculpted. It is her writing that captivates me most though – haunting, dark and hilarious stories from a hugely imaginative mind.

It is a glorious day and walking through Phoenix Park I spot a big fallow deer in the trees. There are lots of people jogging in a Guinness Triathlon. On a hill is the Magazine Fort, which features in Finnegans Wake. As does the village of Chapelizod down below with a pub called the Mullingar Inn which claims to be the setting for ‘all the characters and elements of Finnegans Wake’. It has a James Joyce Bistro – closed.

This evening I am seeing something not Irish, again at Project: Three Fingers Below The Knee which is written and directed by Tiago Rodrigues, produced by Mundo Perfeito, and performed by Isabel Abreu and Gonçalo Waddington.

On 25 April 1974, the Carnation Revolution overturned forty eight years of fascist dictatorship in Portugal. In the national archives theatre-maker Tiago Rodrigues found a mountain of documents relating to theatre, as it existed under that regime. He was particularly taken with accounts by the censors of what they would or, more frequently, wouldn’t allow on stage. Unsurprisingly, several modern dramatists were immediately censored – O’Neill, Max Frisch and Brecht – but also plays by Shakespeare and Moliere. In Three Fingers Below The Knee, Rodrigues casts the censors as playwrights. ‘Let’s see how you cope with this,’ he seems to say.

The stage furniture, a chaise-longue, other fin-de-siecle chairs, is covered in polythene as if to suggest the newness or cleanliness of this artform called drama. There is a clothes rail from which the two actors, in their undies, select costumes.

Surtitles switch between translation of the spoken text and quotations from plays. It is theatre about theatre, and to a theatre festival audience amusing to hear the denigration of several playwrights whose work is being shown this year.

The performance style is parodic and direct to the audience. They go into comic raging over Beckett, they re-write a censored Shakespeare play, they fight over Desire Under the Elms – the play was banned but the film wasn’t. Much of the censorship is against women (from Iphigenia to Masha) and this is illustrated graphically with Abreu writing on her body with blood red lipstick.

It is clear that the regime of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar considered his citizens so totally ignorant (‘the public is Catholic and simple’) that they wouldn’t understand Brecht, so why stage it? One determined director submits Max Frisch’s play Andorra to the selection panel five times. It is rejected each time, even with the necessary changes made.

The text is constantly playful and thought provoking and the performance style has a refreshing openness to it. The surtitles become part of the questioning process, the staging undermines the action, the film sequences are bizarrely static – yes, that’s what we want!

The Festival club is an upstairs room in a glamorous nightspot called Odessa. Unfortunately it is rather sparsely populated tonight and there are other drinking sheds in the city with more appeal.

Day Three: Sunday 6 October

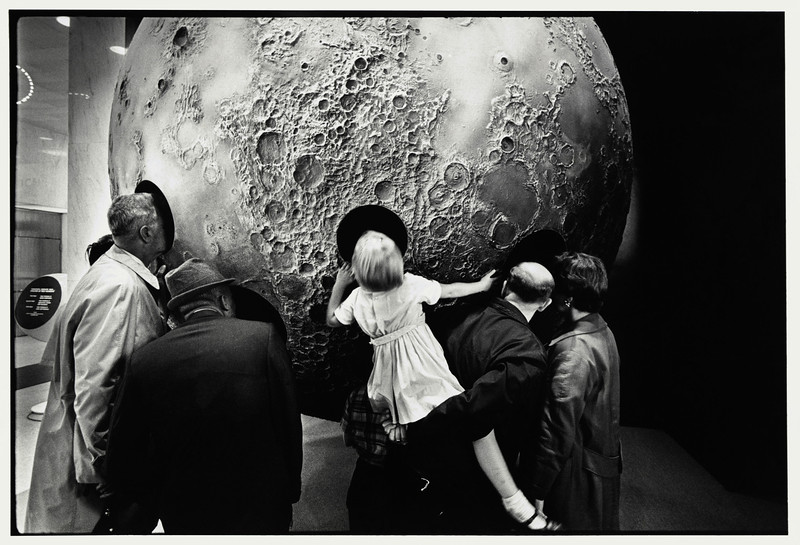

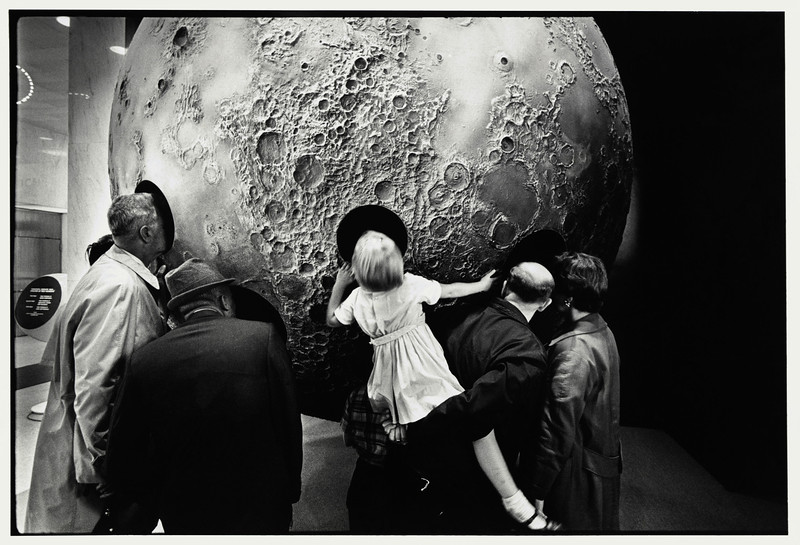

Gare St Lazare Players, Waiting for Godot | Photo: Eliott Erwith

Looming over the skyline from a huge tower is an advert for The Dublin Lockout exhibition. It’s on at the Hugh Lane gallery (which also houses Frances Bacon’s original Soho studio). The Lockout 2013 was a pivotal event in Irish history; a stand-off between the bosses, notably William Martin Murphy, owner of the Dublin Tramway Company, and the unionised workforce. It resulted in the infamous Bloody Sunday. Looming over O’Connell Street is the statue of the workers’ hero, James Larkin, arms aloft as if in proclamation. Larkin is Liverpool Irish and another exile; he moved to America to try and galvanise the unions there.

A matinee at the lovely jewel box Gaiety Theatre – Waiting For Godot by Samuel Beckett, in a production by Gare St Lazare Players Ireland and Dublin Theatre Festival.

Here’s a Pozzo that has been dividing critics, and perhaps audiences, during its run.

This Godot is set on a circular stage, a lunar landscape reflecting the huge moon that hangs at the back, waiting to rise. The tree looms starkly down from above. Estragon (Gary Lydon) and Vladimir (Conor Lovett) a fairly sprightly pair, are natural clowns with a warm rapport and at ease with the language and rhythms of the text. Pozzo enters, with Lucky in tow, and we are further thrown into the world of the circus. Gavan O’Herlily has the looks of Wild Bill Hickok and the voice of Orson Welles. He is huge and ebullient, bellowing out commands to the luckless ‘pig’ yet showing the weakness of his class: he is unable to sit down unless invited.

Lucky (Tadgh Murphy, last seen with a very bad haircut in The Walworth Farce) gives a tour de force gallop through his speech which draws applause.

There is beautiful lighting by Sinead McKenna and the costumes and design is exemplary. Director Judy Hegarty Lovett has many productions of Beckett under her belt with this company, and it bears their trademark purity of vision and economy of movement. To see Vladimir skip about, doing his exercises, is quite a coup de theatre.

In the second half, with leaves on the tree, a blind Pozzo and ever more frustrated pair of Godot waiters, the action dips slightly. But overall it’s a really effective and effecting production, finding lots of humour in the text without distracting from the mystery and misery of the story.

Back to the Project for the final show of the weekend: Dusk Ahead by Junk Ensemble.

The dance space is patterned by strings of wire and elastic, glimmering in crepuscular light (designed by Sarah Jane Shiels). Three blindfolded dancers enter, their passage led by a couple ringing hand-bells. It is apparent that all is not well in this silvery place, in this hour before darkness that we call twilight or dusk.

Episodes follow to illustrate this tension. Couples are tied to each other by their hair, by a lasso, by their mouths. This kissing duet is accompanied by the noise of a pomegranate being squelched. There is much grappling after each other, sometimes in a state of blindness, at one point framed by a waft of green smoke. The space is well used and the choreography, by Megan and Jessica Kennedy in collaboration with the dancers, is quirky and occasionally dangerous. At times, over-used devices distract from the originality of the piece, a dancer walking across a row of upstretched hands, or falling backwards in the arms of others for example. But all the performers are highly watchable and skilled.

There is a fabulous composed score by Denis Clohessy that perfectly matches the eerie fairytale atmosphere of Dusk Ahead. Live cello by Zoe Ni Riordain, accompanied at times by the whole cast on a variety of instruments and in song, is subtle and effective.

It is a shame that it goes on for too long; an episodic piece like this says what it set out to say after about forty minutes. We don’t need to see the wolf twice. We don’t need so many varieties of containment and release. The ending, when it comes, is beautifully simple and stark. One dancer, one light, the small hand gestures that opened the show. Sometimes, less is more.

Leaving Dublin on a fine Monday morning, knowing the Festival is still going full throttle, is quite a wrench. But memories have been gathered, and will endure.