The length of the space is full of dark brown earth. There are little illuminated cities and towns across the landscape. Stage left stands a pilot. ‘We know he is a pilot because of his uniform’ is a repeated refrain in this story of eruptions and explosions, environmental and emotional. From the muddy mounds emerge Clerke and Joy, followed by volcanologist Dr Mike Cassidy, the three of them taking us on a journey through the formation and effects of some of the world’s key volcanoes.

The performance combines wild, naïve dancing, sharp text, experiments and scientific fact. There is filmed imagery as a backdrop and an eclectic mixture of songs old and modern.

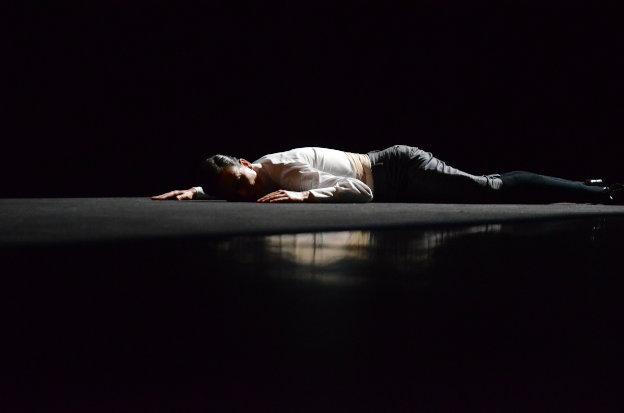

Clerke and Joy combine these disparate elements whilst maintaining a strong through-line and friendly conversational tone. The pilot (Adrian Spring) is the pivot around which the story revolves. He has been grounded by Eyjafjallajökull, the Icelandic volcano whose ash-cloud caused enormous air-traffic control issues and blighted the lives of thousands in 2010. A sad, solitary figure, bearing with grace the sorrow of those affected whilst dealing with his own life troubles.

Volcanoes are given personalities: Mount Pelée is a sad comedian with bad Icelandic jokes, Yellowstone is represented by a balloon blowing up competition that ends in the inevitable pop, and Vesuvius is a begrudging Italian (‘It’s all Pompeii this, Pompeii that…’). The ash-cloud itself is talcum powder, a pungent and familiar smell, linking childhood with old age and adding to the general chaos of the set.

As a world premiere, and a one-off performance, it’s a cracking start and very enjoyable. Clerke and Joy’s intention is to view big global events through the lens of the everyday. Volcano succeeds in this. It evokes disasters with feeling but not sentimentally; it is funny and moving and the performers have an appealing and sisterly warmth.

The show ends with the Northern Lights and some witty film credits. It is a hard balance to strike to not make light of disasters that have affected millions of lives, but Clerke and Joy’s lo-fi show manages to make us think and enjoy ourselves.