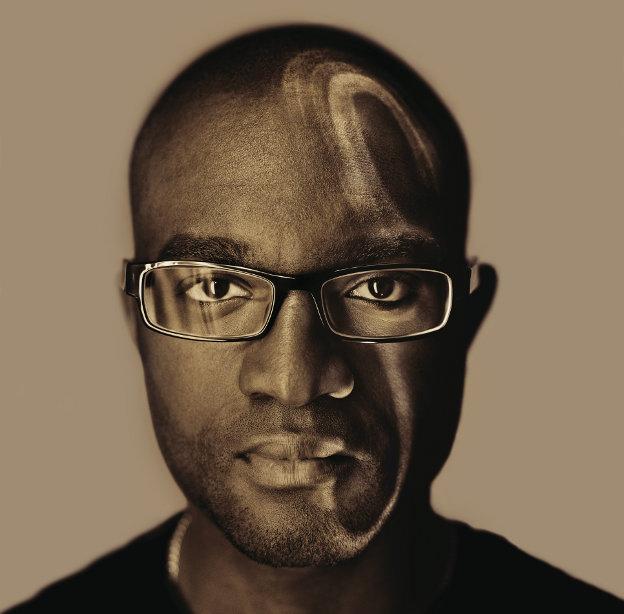

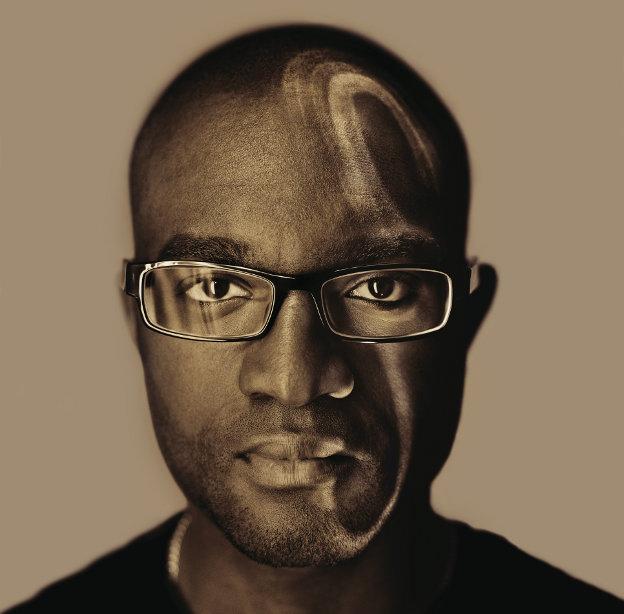

There are several pairings in Black T-shirt Collection, the third work by Nigerian-born Inua Ellams, who has enjoyed a swift ride to becoming a playwright of national status since his first production in 2009.

First, there is black and white, the colours that define the set. There are black blocks, a white cardboard box, a mono animation projected onto the back wall, and then there are the black t-shirts with white slogans that become the defining symbol of the play.

Inua introduces his protagonists, brothers Mohammed and Matthew (two ‘M’s), one Muslim and one Christian, one natural and one fostered. The rest of the family are two women, the mother and a sister.

The play begins with the announcement of the death of Mohammed and works backwards in detailing how he met his end. It is not altogether a linear narrative and moves across time and continent elegantly as the story unravels.

Inua is primarily a poet. His language is rich, defining place and atmosphere in bursts of prose or rhyme that repay close attention. There is a recurring motif of light filtering through dust, of things not quite in focus. This feeling of blurring vision mirrors the tale being told.

Matthew is an artist and entrepreneur, the younger of the brothers. Mohammed is a social creature, outgoing, with an easy rapport with his neighbourhood mates. He seems at home in his skin. Matthew reveres him and they have a close relationship despite their different religious backgrounds and parentage. So close that when Mohammed is outed in a clinch with another man, Matthew insists they flee Nigeria together.

Here the plot whizzes along with speed, journeying to Egypt, London and eventually China as the T-shirt business becomes a worldwide brand. There are encounters with PR folk and kindly hosts, they upscale to production lines and distribution contracts, and fame and fortune come quick. The demands on the brothers naturally causes tension between them.

The heart of the piece gets clotted up in this socio-political landscape. In the earnest need to make a statement about globalisation and exploitation of labour, the nub of the story retreats.

Too many characters lack sufficient depth, the descriptions of the business world are superficial, and the brothers, who have such strongly defined characters, begin to become caricatures.

I longed for it to remain focused on Nigeria and Egypt. We could have learned more about being a gay man in a dangerous country, about the massacre in Jos and the religious divide. About the family left behind which was given very scant coverage. It may be that these themes were investigated in the previous plays, and thus Inua felt the call to extend his geographical horizons. But it made for a long listen, with little visual distraction.

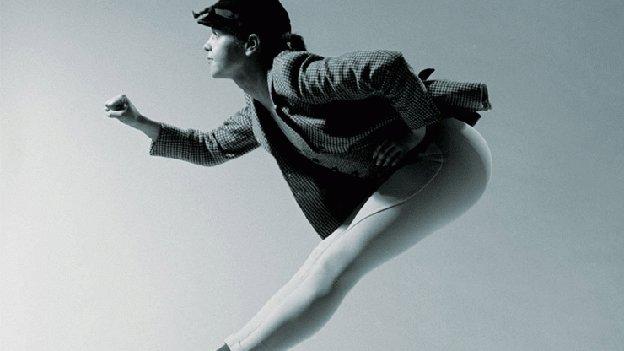

Inua is a fine presence on stage, confident and in full control of his material. The movement was a little too illustrative in places, but overall his delivery is strong and his voice certainly one that needs to be heard.

If Black T-Shirt Collection was intended to be a dynamic overview of globalisation from an unusual perspective, for a young audience at the National Theatre and around the country, it hits the right buttons, as its reviews to date support.

www.inuaellams.com