Two moments make you hold your breath: a man deftly sweeping a small girl into his newspaper lair; and a man’s whispered description of the girl sitting close to him, ‘I can see a freckle just above her mouth’.

It was always going to be risky, this bringing together of grown-up male professional dancers and young girls who dance for fun. Fevered Sleep’s co-directors David Harradine and Sam Butler have long been making theatre, installations and film with and for children. They began thinking about Men and Girls Dance four years ago, with a primary interest in the opposing aesthetics of bodies at different ages, of different gender, and with different dance ability. It soon became so much more, as just the juxtaposition of the words in the title, let alone the physical presences on stage, are so laden with political and moral subtext. The conversation opened out, and the process of making the show grew with input from its supportive developers, including South East Dance.

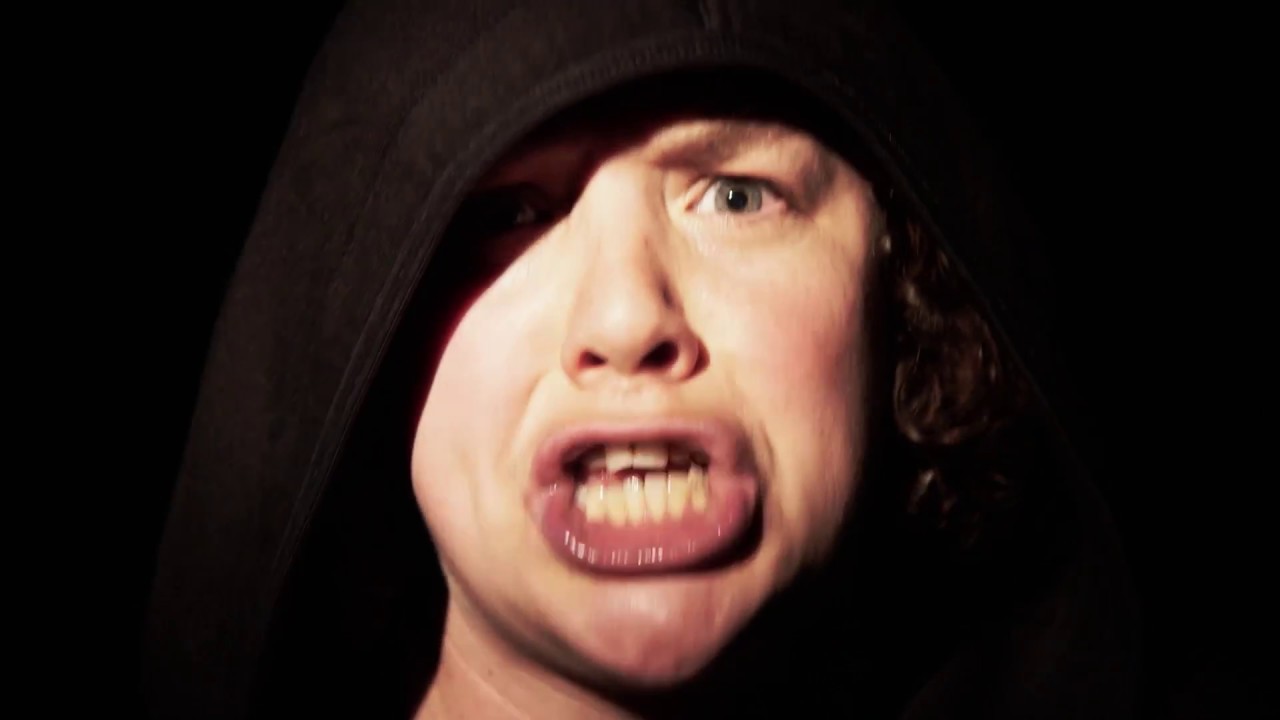

So why a ‘newspaper’ lair? Sheets of newsprint are the backdrop, dancefloor, scenery and props on the wide stage. They are mischievous characters, concealing grown men, smothering children, forming into a Golem or a big, papery head. They are the tabloid press of course, predicated on inciting rage and fear, and the cast gets to rip them up, build harmless monsters, and vanquish demons. This push and pull runs through the whole piece, setting up a scenario that could become dangerous, then doing a switch. The man describing the girl in such forensic detail is later similarly, and just as intimately, described by a girl.

The messiness of the newspaper and the initial interactions of girls and men suggests a playground, with playmates being teased and tested, a bit of tag, some mirroring dance exercises. There is whispering and giggling in corners, bonds are being made. Chords of organ music ring out and Nina Simone sings ‘I wish knew how to be free’ as gradually a shared dance language emerges, giving the girls and men permission to hold and be held, and allowing the audience to relax.

As the relationships between the nine girls and five men get bolder, the choreography starts to include lifts and spins, rising from floor level, where the artists have been of similar height. The girls begin to dance more freely too, full of expression and their own quirky individuality, in contrast to the men who, with one exception, are all of the bearded, tattooed variety. Words become more important, the girls commanding the microphones to describe the movement, captioned live for this show by Stage Text. Some material is improvised, there is no named choreographer (dancer/maker Luke Pell is an associate artist), and the dance itself is less engaging than the interplay between the performers. Musically the piece is a mix of soundbites, quotations and lyrics, interspersed with instrumentation by Jamie McCarthy. There is variety of style to the soundscape (by Harradine and Butler) and the occasional, interesting distraction, but it lacks tonal range until near the end.

It’s the Ting Tings played loud that announces the finale, bursting out in a joyful and gymnastic series of lifts and twirls, runs and leaps, full of energy and passion. One small girl is at a point of stillness during this controlled chaos – she holds our gaze as if to say ‘it’s cool, we are all ok’.

There was always going to be a standing ovation: it’s implicit in the work and the audience profile, and it is beautiful to watch these young bodies in motion, taking risks, giving themselves to an intense and physical relationship with a big, male, stranger. The men are tender, caring and aware of their responsibility to the girls and to the work. It must have been a fascinating and fulfilling two weeks making the piece together, and rather life-changing to perform. The accompanying programme, a newspaper of course (the Brighton and Hove Edition – the girls are all local) expands the conversation with commentary and reflections from participants and observers. It’s an enlightening read.

Fevered Sleep want to create tension in the audience, to let our imaginations be fed by those tabloid headlines. In just ‘putting it out there’ they put all the risk on us – we make the dark connections. Men these days are anxious about taking their kids to the park for fear of accusing looks, and very few are applying to be teachers. We think about the child’s vulnerability and of histories kept hidden and the abuse of innocents. Of course we do. But in the show, whilst there are those moments of real unease, there is nothing so genuinely provocative as in Kabinet K’s Rauw, where children are the playthings of adults, or Gob Squad’s teenage apocalypse Before Your Very Eyes, or anything involving kids by Ontroerend Goed. It is a more tempered beast, pushing at the bars of the cage, keeping us safe.

I’ve always found Fevered Sleep’s work memorable more for its interrogation of ideas and sense of aesthetics rather than its emotional impact. An Infinite Line, On Ageing, Above Me The Wide Blue Sky are all layered and carefully constructed pieces, visually enchanting but with a certain coolness. Those watching Men and Girls Dance who were parents, or whose childhood relationships with men were either closer or more invasive than mine, might have got the goose-bumps or the lump in the throat that evaded me. Apart that is, from at those two special moments described at the start, and the lasting image of the girl with the deep, unflinching eyes.

Men and Girls Dance by Fevered Sleep is produced in association with Fuel.